Who Most Benefits From MyRAs: Savers Or The US Treasury?

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

By executive order of the President of the United States, as announced in the State of the Union address, there is now a new type of tax-advantaged retirement account.

These are the MyRAs, the user-friendly "my retirement accounts" for small investors, that are presented as being one part of the campaign to help close the income and wealth disparity gap in the US. And one of the issues that is identified as being part of that gap is that the poor and middle class have relatively little money in retirement accounts when compared to the wealthy and the upper middle class.

So the United States Treasury is offering a no-fee and very convenient means for low income and middle class investors to build retirement wealth. And this article will explore, based upon what is now known about these new accounts, the advantages and disadvantages for investors.

We will also take a look at the potentially extraordinary advantages for the United States government when savers choose MyRA accounts. Which may raise the question about whether our seemingly benevolent government is truly attempting to help "close the income and wealth gap", or whether it is instead targeting what is generally the least financially-educated portion of society, for the direct financial benefit of the United States government.

MyRAs From A Saver's Perspective

MyRAs appear to be a new variant on Roth IRAs, which means that unlike a 401 or 403 plan or an IRA, there is no ability to deduct the retirement account contribution. Instead, taxes are paid to the government in full as they otherwise would be on income. The tax advantage comes on the back end, in retirement, with interest earnings and principal withdrawals being tax-free.

Now MyRAs are not invested in traditional mutual funds, but rather represent a direct investment with the United States Treasury for the purpose of purchasing what are effectively US Treasury bonds. It appears that yields would likely be similar to what federal employees currently get in their Thrift Savings Plan Government Securities Investment Fund program, which was 1.5% in 2012.

A MyRA is very convenient to open up, with an initial contribution of $25, subsequent minimum contributions of as little as $5, and an annual limit of $5500. Moreover, no financial advisor is needed; this is supposed to be a very simple and easy program for bringing a new kind of investor into retirement accounts.

Now let's take a closer look from a saver's perspective.

1) No Initial Tax Benefit.

There is no upfront deduction for opening the account. So the saver, unlike if they opened up an IRA, takes a hit on the front end by paying taxes in full.

2) Very Low Interest Rate.

There is an extraordinarily low interest rate paid with these accounts. As part of what is at this time a long-term program of keeping interest rates near zero in the short term, and also quite low over the medium and long term, US treasury bond yields are some of the lowest in history.

A 1.5% rate of return is negligible. Even when invested over the long term, it fails to compound anything like a traditional retirement account investment might do.

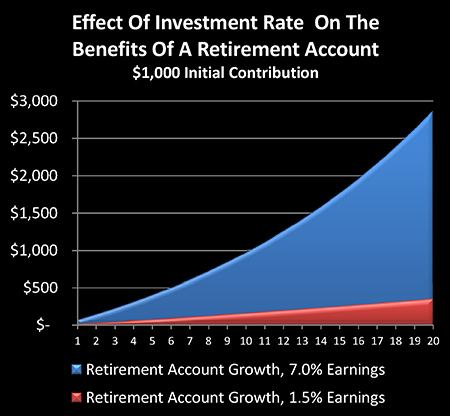

The graph below shows the difference in earnings from a retirement account invested at 1.5% over a 20 year period, versus a retirement account invested at 7%.

The "magic" that is supposed to build wealth in a retirement account over time just isn't there, given our current government-induced world of very low interest rates.

3) Steady Loss Of Purchasing Power.

The yield on short term government securities is less than even the official rate of inflation, let alone the costs we've all been seeing for actual spending when it comes to food, education, medical insurance costs, and the like.

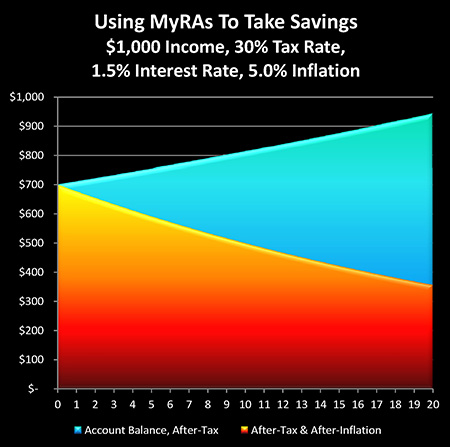

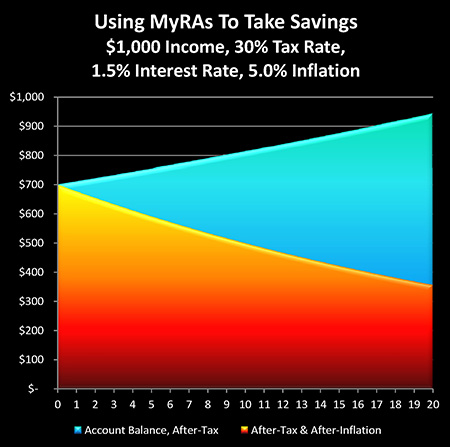

The above graph combines our first three MyRA components to see how they work in combination.

Looking at $1,000 in income, and assuming a 30% marginal combined federal and state tax rate – because there is no tax deduction, the saver can only deposit $700, rather than the $1,000 they would be able to with an IRA or 401 plan.

The blue area shows how the balance in the account would climb over 20 years if invested at 1.5% – it wouldn't even make it back to the initial $1,000.

With our current monetary system, the purchasing power of the dollar will be dropping each year. There's nothing controversial about that – it's the stated goal of the Federal Reserve as well as other central banks around the world, each of whom have minimum inflation targets.

The graph uses a conservative example of a 5% rate of inflation, and even with that – the value of a $700 after-tax account contribution steadily declines to a value of $355 in after-inflation terms over 20 years.

So instead of building wealth it has the opposite effect – the wealth slowly bleeds away over time. And even if you use the official inflation figures from the last 10-15 years (about 2.4% over the last 15 years), the rate of inflation is still higher than the interest rates that appear likely to be paid in a MyRA. So the savings still decline in real purchasing power terms each year, even if the rate of decline is not as great as that shown in the graph.

4) Ending Tax Treatment Uncertain.

So what is being offered to the investor is a very low-yield account, with no upfront tax benefits, that is likely to steadily lose value over the years if government-manipulated interest rates stay where they are.

Given how deeply in debt the United States government is, and the extraordinary burdens of paying for state and government pension plans as well as Social Security as well as Medicare, the one thing we do know is that the United States is likely to be in even greater financial distress five, ten, fifteen years now than it is right now. And I think we should count on a pretty good chance of a comprehensive change in the tax code regarding retirement accounts.

MyRAs From A Governmental Perspective

Now, let's consider MyRAs from the perspective of the United States government.

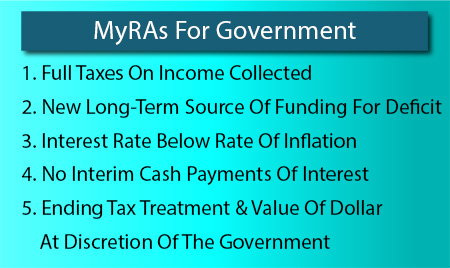

1) Full Taxes On Income Collected.

The US government is running major deficits and it needs all the taxes it can get. This creates difficulties with IRA or 401 type plans because tax payers get tax deductions for making retirement account contributions.

With the new MyRAs being a modified form of Roth IRAs - there is no deduction, and thus the government collects all of its taxes this year.

2) New Long-Term Source Of Funding For Deficit.

The United States government is deeply in debt, with the over $17 trillion in outstanding US federal debt being approximately equal to 100% of the size the economy. It is also running a substantial deficit, currently officially projected at roughly $750 billion per year.

The US government badly needs funding for that debt. And MyRAs are intended to increase the number of people who are lending money to the United States government, so that it can go out and spend that money.

That's the crucial thing to keep in mind about what happens when someone makes a contribution to a MyRA or buys a savings bond – it's not like the government is taking your money and setting it aside like an investment firm or bank might do.

No, the whole point is that the government spends that money immediately, and there are no independent assets in the account at that point. The money has either gone to roll over bonds that must be redeemed, or it goes to funding new annual deficits.

The only asset in the account is a promise from the US government to pay the principal and interest at some future point in time.

3) No Interim Cash Payments Of Interest.

As covered in my recent article (linked below), "Could A Compound Interest Wildfire Threaten US Solvency", the US government currently does not pay any principal or interest on the debt out of its tax revenues, but rather it borrows all of the money to make interest payments, just as it borrows all of the money to roll over principal payments that come due, and it borrows additional money to fund federal government spending that cannot be supported from tax revenues.

And it is a burden for the government even at current very low interest rates to meet interest payments. Indeed, interest payments on US federal debt are more than half the size of the annual federal deficit at this point, as covered in that article. (And as also discussed, there is a lot of information value there when it comes to the likelihood of rates going up in MyRA accounts.)

The beauty of a MyRA from the federal government's perspective is that not only does it get a source of funds that can be spent here and now, but it doesn't have to make any cash interest payments until the retirement account is cashed out. Instead, as each interest payment comes due, the account balance rises instead of cash being paid out, so effectively the MyRA investor is locked into taking their earnings each year, and lending those to the government as well.

And if the cashing out doesn't happen for the next 20 years, that means the US government does not make any real (cash) interest payments during that time, but rather there's just the very low paper compounding of interest payments that occurs within the retirement account.

4) Interest Rate Below Rate Of Inflation.

One and a half percent is a very low interest rate for a deeply-indebted nation in a great deal of financial trouble.

It is indeed a negative rate on an inflation-adjusted basis even using official US government inflation statistics. And if we use something more in line with reality such as let's say the 4%, 5% or 6% range (as shown with our saver example), then we have a substantially negative inflation-adjusted rate of return.

Now how many of MyRAs' intended audience – who are acting without the benefit of a financial advisor and are making $5 contributions when they have the cash available –are likely to fully understand the term "negative inflation-adjusted rate of return" and its implications?

Some will – there are of course some very intelligent and well-educated people in lower income brackets in these times – but probably most won't, and that's likely one of the key reasons for why this program is set up the way it is.

5) Ending Tax Treatment & Value Of Dollar At Discretion Of The Government.

As a debtor who owes a fantastic amount of money and is running major deficits each year, while having ever-increasing financial problems with an aging Baby Boom who have been promised retirement benefits – the US government has enormous incentives to repay debts in dollars that are worth much less than they are today.

As the proportion of those collecting Social Security and Medicare rises each year when compared to those still in the workforce, the government will also be under heavy pressure to change the tax code in order to raise revenues. This could take the form of increasing tax rates, or it could take the form of changing the treatment of tax shelters – such as retirement accounts – or it could involve both.

MyRA contributors don't receive any financial benefits until they retire – whereas the government receives all of the benefits up until that time. And whether the rules will be the same as they currently are when it comes to cashing out retirement accounts in 2025 or 2035 – that will for the government in 2025 or 2035 to decide, depending on its financial situation at that time.

Understanding The Bigger Picture.

A MyRA is a textbook example of Financial Repression in progress.

Financial Repression is a widely-understood and accepted concept among professional economists, although the general public never seems to hear too much about it.

As explained in my article linked below, "Financial Repression, A Sheep Shearing Instruction Manual", Financial Repression is how the US repaid its World War II debts during the late 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, and the US government has returned to this policy in recent years.

It is a deliberate program whereby a deeply-indebted government pays lower interest rates on its debt than the rate of inflation, which reduces the real value of the amount of debt outstanding.

However, it requires a source of funds – from a preferably captive audience. Measures must be taken – and this is a core part of Financial Repression – to get as much money from the public as possible invested into bonds, in a program that works to the direct benefit of the government (and to the detriment of the saver).

Looked at from that perspective, MyRAs are instantly identifiable not as a means of closing the income gap, but as a means of increasing the flow of dollars from the poor and middle class to the federal government, for the direct financial benefit of the federal government.

Also, for those of you who attended the Overcoming Monetary & Political Risk workshops or have viewed the DVDs, this development with MyRAs is exactly in line with the principles that we discussed and what we said to anticipate.

As discussed, retirement account changes in the future are almost certain, and they will be presented in one way, which is as a benefit to the public or as a very subtle change, when in fact if we look at the bottom line, each change will strongly work to steer retirement wealth from individual investors to the federal government.

The Flaw With MyRAs

There seems to be one rather big problem with the federal government's plan to financially benefit from this supposedly great program for lower income and middle income savers. And that is that because of the changes in the economy and the financial system, this targeted group of people has very little to no money for making investments.

Wages have not been keeping up with even official inflation, the retail industry is in dismal shape, we have what is now more or less calcified structural unemployment with a real unemployment rate that is closer to 20% rather than below 7%, and the lower income and middle-class of the United States are in severe financial straits.

So it is unlikely that the dollars saved in this program will be significant for the federal government, and it is also highly unlikely that more sophisticated investors will choose to participate in it.

Nonetheless, there is enormous information value here for all of us when we see the attempt that is being made.

With the big picture being a deeply-indebted government that can't meet ongoing principal and interest payments without still more borrowing, setting up a wolf in sheep's clothing program where the purported purpose is to help people in the lower and middle class, but indeed the end result is something quite different indeed.