| Daniel Amerman & The Turning Inflation Into Wealth Mini-Course | |||

| Home | Inflation & Wealth | Author Info | Crisis, Books & DVDs |

| Bailout Lies | Deflation & Inflation | Inflation Supply Shock | Retirement Reality |

Daniel R. Amerman, CFA, DanielAmerman.com

When a financial bubble bursts – can it

be reflated? And what are the risks for

all of us the reflation attempt fails?

In this article we will briefly review

the six factors that came together to create the real estate bubble in the

United States. As we will cover, the

government has deemed a return to a normal housing market – one which is governed

by market forces – to be politically unacceptable. Instead, an artificial mortgage market has

been created with massive interventions in three different categories as the government

attempts to reflate the housing bubble. Quite

a risky undertaking, but the politicians have decided they are willing to risk

everything the taxpayers and savers have, in an attempt to remain in

office. These interventions include the

Federal Reserve effectively creating money out of thin air to fund almost the

entire mortgage market at below market rates.

We will explore why the three interventions will not succeed in

replacing the six sources of the bubble, and the severe risks for all of us

when attempting the economically impossible becomes politically mandatory. We will close with a discussion of the likely

implications for the housing market and the value of the dollar, as well as a

brief discussion of alternative solutions for protecting your net worth.

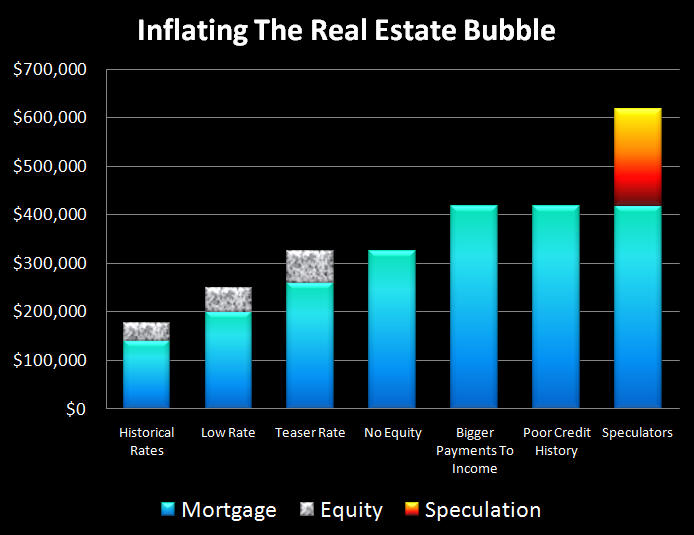

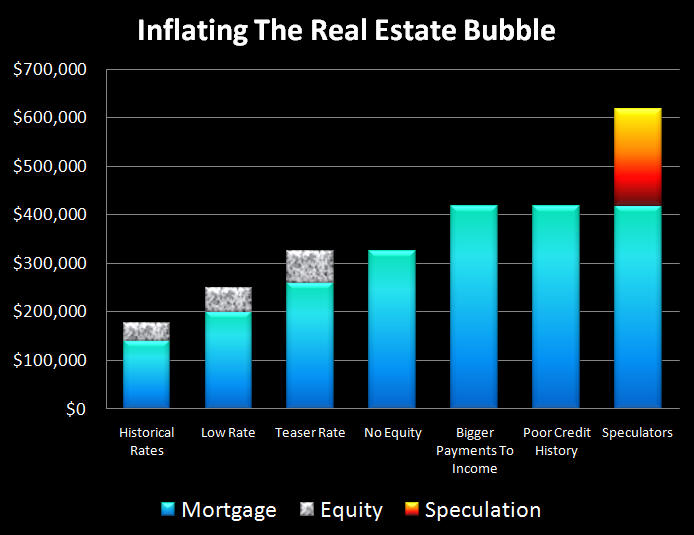

A number of factors came together to

create the housing price bubble that was experienced in the United States

during the early to mid 2000s. Perhaps

the central element was a quite deliberate Federal Reserve easy credit policy

that led to the lowest mortgage rates that had been seen since the 1970s, which

made purchasing houses the most affordable that they had been in a generation.

Qualifying for mortgage loans is not so

much dependent on home prices, but rather the ability to afford mortgage

payments. As an example, let’s consider

a family with the median household income for the United States in 2009 of about

$50,000 per year (Census Bureau estimates).

Pre-bubble underwriting standards

were that mortgage payments should take no more than 28% of household income, which

meant $1,167 a month would have been the maximum available for mortgage

principal and interest payments.

According to Freddie Mac statistics, the average 30 year fixed mortgage

rate between 1972 and 2006 was 9.31%. If

we take the median $50,000 per year income and an average 9.31% mortgage rate,

that means that the exactly median household in the US qualified for a $141,000

mortgage, and assuming 20% equity, a $176,000 house.

During the rapid growth of the housing

bubble, fixed mortgage rates spent much of their time in about the 5.50% to

6.00% range. When we change our mortgage

rate to 5.75%, then a family with that same median income of $50,000 per year

can now qualify for a $200,000 mortgage, an increase of about $60,000, or almost

half again as much mortgage (and home price).

During the peak insanity of the housing

bubble – an insanity in plain view that was enabled by the federal government as

well as Wall Street and the rating agencies – subprime mortgages were being

underwritten at one year teaser rates such as 3.5%. At such rates a family with an income of $50,000

a year could “afford” a $260,000 mortgage, or almost twice the mortgage of a

decade before, which enabled a near doubling of real estate prices. At least until the interest rate

contractually reset, at which time the family would have no known means of

making the payments, but Wall Street and the rating agencies providing

investment grade ratings were far beyond being concerned with such trivialities

by this point.

However, the plunge in mortgage

interest rates was not enough to create the full housing bubble. Even a $260,000 mortgage wasn’t sufficient to

buy a new home in many desirable markets where prices were surging; the income

simply wasn’t there to sell the average home to the average worker. Many people also lacked the large down

payments, the equity component of home purchases. So the solution was to simply allow people to

borrow their down payments in the form of 2nd and 3rd

mortgages that closed simultaneously with the 1st mortgage.

An additional hurdle was that the

historical standard of 28% or 30% of income was insufficient to make payments

on the new, larger loans. Now, those

standards were far from arbitrary – many decades of mortgage underwriting

history had shown that most people could handle housing payment burdens of that

size relative to their income, but things got “iffy” above those levels. However, in the early years of the new millennium,

accepting those traditional limitations was unacceptable, as not enough people

could buy homes at ever rising prices. So

the standards were changed. People were now

allowed to borrow a total of 35%, or 40% or even 45% of their annual income in

total required mortgage payments (including 2nd and 3rd

mortgages).

With this combination, we were really

getting somewhere in terms of “affordability”.

Take a family with the median national income of $50,000 a year, let

them borrow at a one year teaser rate of 3.50% (with everyone involved pretending

that will be the rate for the entire term of the mortgage), let them use 45% of

their income to cover the package of mortgages that ensures no actual savings

are needed to help fund the house – and they could now “afford” a $418,000 mortgage and a $418,000 home

($50,000 income, 3.5% teaser rate, 45% of income to 1st & 2nd

mortgages).

This was still not enough, however, for

people with a bad history of repaying small loans were being kept out of the

market for large loans. So they were

allowed in with the explosive growth of subprime lending, and were allowed to

borrow their down payments, even while the percentage of income available for

housing shot upwards. Changes in

underwriting standards may sound a bit obscure, but the practical result was

that a family that couldn’t have bought a home of any kind in 1996, due to

their lack of savings and poor credit history, could now buy $400,000 and

$500,000 homes.

So let’s review. Going from a historical average 9.31% 30 year

fixed rate mortgage to underwriting based on fixed mortgage rates of 5.75%

boosts the amount that can be borrowed – and the home that can be purchased –

by 42% (Step 1). Underwriting at a

teaser rate of 3.5% on a one year adjustable rate mortgage boosts the amount

that can be borrowed even more, up to a total of 84% (Step 2). Going from 28% of income being allowable for

housing payments to 45% of income (combined 1st & 2nd

mortgage), separately boosts the amount that can be borrowed by 61% (Step 3). Combining the lower rate and more aggressive

underwriting standard boosts the maximum amount of the mortgage by 196% (1.84 X

1.61 = 2.96), as the amount that can be borrowed by a family with a $50,000

annual income rises from $141,000 to $418,000.

Add in an expansion of the homebuyer pool to include those who don’t

have enough excess income to save down payments (Step 4), thereby increasing

the competition for each home. Add in an

expansion of the homeowner pool to those who have poor histories of repaying

loans (Step 5), further increasing the competition for each home. This 1-2-3-4-5 combination needs only one

more ingredient to predictably set off an explosive rise in housing prices.

Home prices rose as payments fell and

more buyers entered the market; human nature came into play and a speculative

frenzy was born (Step 6). People looked

at the sharp home price increases that were happening, month after month. They saw the new easily available credit that

was flooding the market, with banks competing to offer massive loans allowing

the purchasers to buy houses with essentially no money down, even if the

borrower didn't have the means to pay for it.

Millions of people quickly saw

that buying and flipping homes would make them far more money than just about

any job for which they could qualify. So

a speculative frenzy kicked in that drove prices higher and higher as it drew

more and more people in.

This of course led to an unsustainable

environment. Because of the speculative frenzy, because of the easy underwriting,

home prices reached levels in many metropolitan areas where the average family

couldn't afford the average home even at very low mortgage rates. On the

underwriting side, loans were being made to individuals with poor credit histories

at teaser rates, where those individuals had no known means to make their mortgage

payments when the interest rate inevitably reset as part of the contract. The time had come when the popping of the

bubble was inevitable.

In the aftermath of this bubble it is

quite clear what the housing market wants to do. Like any market that is

recovering from a frenzy, what it seeks is sustainable equilibrium. Those are

the fundamental economic forces in play here.

What the housing market wants to do is

reach a place where the average creditworthy and stable middle-class family can

afford an average home, spending no more than about 30% or so of their income

on housing. For this to happen, prices

truly must be much lower than they were at the peak in places like Southern

California, Las Vegas, Arizona and Florida. Those were simply unreal prices. If the average home is completely unaffordable

to the average buyer, but there are sellers who must sell, then the basics of

economics tell us that prices must drop until sellers can find buyers – as with

any other market.

Obviously, the specifics vary by the

market, and this doesn’t mean that three bedroom homes on big lots in good

neighborhoods suddenly drop below $200,000 in Southern California. But it does mean that townhomes with postage

stamp lots and a long commute have to return to a place where mortgage payments

are realistically affordable for a college graduate earning the prevailing wage

in that area.

In terms of mortgage rates, where the

market wants to go is to a place where private lenders are bidding against each

other with gusto to make mortgage loans, because the risk return combination is

healthy and attractive to them. They are being substantially rewarded for

taking the risk of funding housing.

Now what this translates to is

materially higher mortgage rates, almost by definition. The reason the Federal Reserve has taken the

unprecedented step of maintaining massive monetization to fund the mortgage

market is that the alternative of mortgage lending by private participants

would have been at unacceptably high interest rates. If true market rates return, this likely means

that payments rise for the given price of a house, which then drives down the

prices still further until home prices reach a point where – at market interest

rates – the average family can afford the average home.

Unfortunately this return to normalcy

is very difficult for many millions of truly innocent homeowners. By truly

innocent I’m not referring to the people who in many cases were quite knowingly

speculating in the housing market, or to those who never should have been able

to buy a home in the first place. No, the

truly innocent are the responsible, middle class families who could afford a

home before this bubble occurred, and would have a healthy equity in their

homes right now in ordinary circumstances. However, during the heart of the housing

bubble they needed homes, and had no choice but to pay much more than what those

homes should have been worth.

Which has left them with significant economic

damage at this point, as they are effectively underwater in their mortgages by

quite substantial sums. These families

are essentially locked into their homes for the indefinite future, unable to

leave, unless they either take a major loss on their home and come up with cash

to pay for that, or destroy their credit rating. These millions of families are the true

victims of the reckless actions of Wall Street and the Federal Reserve in

creating the bubble.

There is the economic reality which we

were just reviewing, and simultaneously there is something entirely different: political reality. Looking at the situation, the politicians in

the United States collectively determined that they could not accept economic

reality. There was too much bad news there, which would lead to too much voter

discontent, which would translate to too many incumbents losing elections.

So the decision has been made to make

an all-out effort to support the housing market, regardless of the cost and the

risk.

Now, we're not really talking about

cost and risk for the politicians. They

are not, nor have they ever been, the ones who are truly bearing the risk. Rather, it is you and I bearing the risk and

bearing the costs. The politicians have

made the decision that there is no limit to the cost they're willing to pass on

to all of us to get housing to a politically acceptable place, and there is no

limit to the relative risk that they are willing for us to take. In other words, there is no limit to the financial

risk for you that the government is willing to take to stay in power.

So a massive, historically

unprecedented intervention by the government has been the result. An enormously expensive intervention by a

government that already couldn't pay its bills.

Even as the housing bubble was created by the convergence of five

mortgage finance factors (not including human nature), the government’s efforts

to prop up housing prices fall into three broad categories.

The public face of the government’s

efforts to support the housing market are the homebuyer tax credits, as

featured in all the headlines. These

are tax credits of up to $8,000 for first time homebuyers and $6,500 for

previous homebuyers. Some estimates are

that total tax credits will end up costing the government about $20 billion in

foregone tax revenues.

This could be viewed as an explicit

partial socialization of home purchases, where homebuyers who supposedly act in

the national interest by purchasing homes are funded by the rest of the

population. Another way of looking at it

is every household in the United States pays an average of $180 each, so a

lucky few households can get up to $8,000 each.

In some ways, this could be viewed as a partial funding of the down

payment for homes, allowing people to participate who otherwise would not, thereby

supporting the market.

The homebuyer tax credits are a very

explicit short term attempt at market manipulation. As soon as the tax credits

stop, the housing market can be expected to seek whatever levels it would've

gone to if the tax credits had never existed in the first place. Indeed, the market may even temporarily fall

further than it otherwise would have, because anyone who could have reasonably

purchased a home and benefited from the tax credit would already have done

everything in their power to do so, thereby depressing the pool of homebuyers

for the months or years after the program ends.

While they are the best known facet of

the government's housing support program, and the only component where the cost

is being openly included in the federal budget and voted upon in Congress, the

homebuyer tax credits are arguably the least important of the big three housing

support programs.

A more important form of governmental

support for the housing market is both more obscure than the homebuyer tax

credits and potentially much more costly to the nation as a whole. As previously discussed, it was the

relaxation of loan underwriting standards that drove the expansion of the

housing bubble as much or more than the reduction in interest rates. The popping of the housing bubble effectively

destroyed the use of private mortgage underwriting standards. Private investors no longer want to take

mortgage credit risks, at least not without payments of substantially higher

fees and severe restrictions on who qualifies for loans. Which would be politically unacceptable.

Therefore, the overwhelming majority of

mortgage financings these days have to meet the underwriting standards of FHA,

Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. These

entities now effectively bear the credit risk – the chance the homeowner won't

make payments and the losses that then need to be taken – for nearly the entire

mortgage market. Since the failure of

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and their takeover by the federal government, this

means that the federal government directly controls virtually all aspects of

the mortgage credit process, determining who gets mortgage loans, how large of a

mortgage loan they get, and under what conditions. The federal government determines the standards

for loan to home value, for payments to income, for what constitutes income for

underwriting purposes, for credit scores, and far more. This is terribly dry and obscure stuff, and not

at all suitable for headlines or passing coverage by TV news anchors, despite

being more important than the far more public homebuyer tax credit programs in

determining how many people can afford how much house in the real world.

Along with the federalization – that

is, the straight up politicization – of mortgage underwriting comes the

complete socialization of mortgage credit risk.

The federal government sets the standards because it is willing to bear

the cost of all the mistakes, for all the loans that go bad, for the entire

housing market.

Except that, of course, the federal

government doesn’t really take any losses.

It’s you and I who take the losses and bear all the risk.

So a more accurate way of phrasing what

is happening is that political appointees under instructions to keep the

housing market propped up regardless of costs – and effectively operating

almost out of view of the media and the public – are taking massive risks in

the name of extending credit to as many homebuyers as possible. Expensive risks that could dwarf the

homebuyer tax credits – but that don’t have to be included in the budget. After all, the losses haven’t occurred yet,

and can therefore be quite easily made to disappear through the flexible use of

optimistic assumptions.

There is no way for anyone outside of

the government to quantify the full extent of the risk, and it is indeed

unlikely that anyone inside the government is keeping track on a multiagency

basis (with real world assumptions anyway).

However, recent congressional testimony about the Federal Housing Administration

can provide insight into a small part of the bigger picture. FHA is in big trouble, with reserves down to

about 0.5% of mortgages insured, compared to the legally mandated 2.0%

minimum. The agency is treating mortgage

modifications by people who previously couldn’t pay their mortgages, as if they

were essentially of the highest credit quality, rather than subprime. Yet at the very same time, the FHA

commissioner assured Congress that there wouldn’t be any problems. A political appointee telling incumbent

politicians exactly what they wanted to hear, which was that the housing market

could be aggressively supported through government guarantees of questionable

but politically desirable loans -without worrying about bothersome technical

details.

The headlines about what has been

happening with the complete politicization of lending standards for one of the

largest loan markets in the world may indeed become quite common – after it is

already too late.

The Federal Reserve had already created

close to $1 trillion through straight-up monetary creation as covered in my

article “Creating A Trillion Out Of Thin Air” for a short-term intervention in

the commercial paper market and emergency bank lending. It was a daring risk, a tremendous risk on a

scale that was unprecedented. On a scale

that risked the value of the dollar itself, and therefore put in peril the

value of all of our savings.

The Federal Reserve succeeded in their

first gamble. The original plan, as

covered in my article ”Containing Inflation Via Unlimited Money Creation: The Fed’s Strategy“, was to quickly return

that cash to the void from whence it came, before the value of the dollar was

jeopardized. However, because of the

problems in the housing market and political requirements, the Fed took a

different approach. They doubled down and more as they took that fabricated money,

and instead of getting rid of it, they just put it back out in a much riskier

strategy than the original one. What the Federal Reserve did was create an

entirely artificial market for mortgages, which means an entirely artificial

market for housing. The Federal Reserve wanted mortgage rates lower than what a

rational private lender would loan at.

So the Fed effectively bought the

entire new mortgage security originations market, essentially funding every

conforming new mortgage that was coming down the pipeline, and thereby funding

the purchase of nearly every home that was being sold in the United States. With

the source of that money being the trillion dollars that had been effectively

created out of thin air. This put a

floor beneath the fall of the housing market, but it didn't create a healthy

market.

The economists at the Federal Reserve

know that this is an unsustainable and risky situation. They know that they can't indefinitely fund

an artificial market in the most real of assets through creating money out of

thin air, with no economic growth to support that money and no taxes to support

that money. So they know that they have

to leave. And they're saying that their

plan is to start withdrawing from the housing market by around the end of March

of 2010, and to steadily pull out. Indeed, the Federal Reserve is already

expanding its list of eligible counterparties for transactions designed to

drain the cash it created from the system, and the New York Fed has been

conducting live trial runs in the marketplace.

There are some complications here, however.

The Fed can do the fiscally responsible

thing and get rid of the excess money and unwind its positions, but what would really

happen if mortgage rates jump 1%? And what

if this shuts down a housing market which is already in pretty bad shape, and

is not responding all that well even to these artificially low mortgage rates?

Even worse, what happens if mortgage

rates rise 2%, and not just the housing market shuts down, but the construction

industry also stops in its tracks? What

do the politicians do at that point?

There are some crucial political

equations that we need to be taking into account here. Being that the midterm elections are

approaching, will the government really withdraw its support for the mortgage

market and thereby the housing markets?

Will the government be willing to endure steadily growing pain as the

economy likely plunges down along with the housing market, with voters feeling

ever more pain every month as the election approaches? Will incumbent politicians of either party voluntarily

lose the upcoming elections for the economic good of the country?

Or will they instead choose an approach

that stretches our fantasy mortgage and housing markets out just a little bit

longer?

That's the problem with a strategy like

this. There never is a convenient time to leave the strategy, because the

markets always want to return to fundamental levels. And the decision has already been made that

those fundamental levels are not politically acceptable. So any exit strategy may be doomed before it

even starts.

Housing prices have temporarily

stabilized, and have even recovered a bit in some areas, but some fundamentals

are getting even worse. Between five and

seven million homeowners are seriously behind on their mortgages, and may be

foreclosed upon at any time. The reason

they haven’t been foreclosed upon is that the banks have been under intense

political pressure not to foreclose on too many homes. This creates another form of artificial

market, where there is an overhang of millions of people living in homes upon

which they haven’t been making payments.

There are strong indications that the pace of foreclosures may pick up

again in 2010, in which case a flood of repossessed homes on the market could

quickly drive down prices.

This wave of foreclosures is however

quite different from the previous wave, because it isn’t about subprime

borrowers. It’s about responsible people

with good credit records who didn’t borrow too much – but have lost their jobs

in the greatest depression/recession since the 1930s. Prime mortgages extended to unemployed borrowers

are what most threaten the mortgage markets now.

Using my background as a mortgage

derivatives expert and author, in a series of public articles in early 2008, I

connected the dots as I saw them, and drew what seemed to me to be the obvious

conclusions: that the subprime crisis

would get much worse, and would have the potential to melt down Wall Street in

a week. Not from accounting losses, but

rather from creditors pulling loans from the highly leveraged financial giants

when they realized the extent of the losses.

I further predicted that the government would not allow this to happen,

and that instead there would be a massive bailout that would not only lead to

huge deficits, but necessitate the Federal Reserve resorting to creating money

out of thin air in an attempt to contain the damages. In other words – what has happened. While a number of people predicted

catastrophe, to the best of my knowledge, this makes me the only person to

accurately publicly predict not just that there would be a crisis, but how the

crisis would unfold, the government bailout, the Federal Reserve’s

monetization, and where the response to that crisis would logically lead: to the place we are covering in this article

in early 2010. In my opinion – this is a

time where some more dot connecting is badly needed.

(The referenced articles from early

2008 are “The Subprime Crisis Is Just

Starting”, “Credit Derivatives Dangers In 2008 & Beyond”, and “Why Inflation Will Trump Deflation”.)

All three components of the

government’s attempts to reflate the housing market are massive and need to be

understood – but they aren’t enough.

What history shows us is that there is no credible reason to believe

that an asset bubble can be successfully reflated in real terms

(inflation-adjusted) by a government.

The irreplaceable element required for an asset bubble is millions of

people who are not just willing, but eager, to risk their own financial

security to bid prices to irrational levels – even after just having been

burned in the same market only a few years before. Bubbles can quickly follow each other when

the market changes, as shown by the housing bubble so quickly following the

tech stock bubble. (Particularly when the

central bank deliberately intervenes to facilitate creation of the second

bubble, in order to mitigate the economic damage from the first bubble.) However, the public has to be able to

convince themselves that the second bubble really is different from the first

bubble that just burned them, and this is near impossible to accomplish in the

same market.

This is why the housing market has not

yet “recovered”, despite desperate and massive efforts by both the Federal

Reserve and the US Government. Everybody

just got burned in the last bubble, and it is very hard to get them to

participate in another bubble with what is left of their savings, particularly

in the midst of depression / recession.

To reflate the bubble requires people risking everything they have to

return prices to fundamentally irrational levels – and it’s no small wonder they

don’t want to do that. As fundamental as

this problem is however, it is also more or less irrelevant as a determinant of

government policy, for the reasons previously reviewed.

The Federal Reserve may be talking the

talk when it comes to the economic necessity of draining its artificial cash

from the system and exiting the mortgage market – but will it really pull out

just as foreclosures accelerate and new mortgage investors fail to return at

below market rates? During an election

year?

The complete control of credit

underwriting standards for the housing market by political appointees, with the

federal government unconditionally guaranteeing the results of those political

decisions – is financial dynamite.

Particularly when the explicit goals for the agencies involved are now

political, in terms of supporting the housing market rather than minimizing

losses. Off budget though they are now,

the eventual financial outcomes of this unprecedented change is sadly only too

predictable.

In more general terms – the question is

one of the public good versus the re-election of incumbents (in both parties,

this is very much a bipartisan issue, and has been so at each stage of creation

and response). If the value of the

dollar and of our investments that we have worked our lives to build are to be

preserved – then this extraordinary creation of an entirely artificial mortgage

market funded by an already bankrupt federal government must be abandoned. Even if the cost is the destruction of the

careers of many career politicians.

How do you think that decision will

work out?

And more importantly, what are you

doing to protect what you have?

We face a tragic situation for many

millions of people who have done nothing wrong.

Government policy and fundamental economics are combining to create a

situation of simultaneous monetary inflation and asset deflation. The government can’t reflate the housing

bubble, but the political dynamics require the attempt to be made. Even at deadly risk to the value of the

dollar, and to a lifetime of savings for many tens of millions of

households. So the value of the dollar

falls, the value of the assets fall, and eventually the fall in the value of

the dollar exceeds the fall in the value of the assets, thus finally creating

the façade of a reflating bubble in nominal dollar terms (but not

inflation-adjusted). False profits, existing only because the value

of the dollar is falling, are then generated across multiple asset categories, which

lead to inflation taxes, and the hapless average citizen ends up simultaneously losing the purchasing power

of their money and the purchasing power of their assets, while paying whopping

tax bills in the process.

This dire situation may appear

overwhelming, and even hopeless, if one is limited to conventional investment

methods. For these methods generally do

not provide solutions for even one of these three problems, let alone the

catastrophic damage that can be wreaked by all three working in

combination. However, the good news is

that where there is crisis there is also opportunity, and this crisis is indeed

rife with personal opportunities. When

we see with clarity and utilize unconventional methods, then simultaneous asset

deflation and monetary inflation can become an environment of investment

opportunity. Indeed it can be a

potentially “target-rich” environment, because so few investors see the world

in those terms.

As one example, this environment

creates major opportunities for precious metals investing. Unfortunately however, purchasing gold as a

simple monetary inflation hedge at the highest prices in a generation with no

protection from inflation taxes may lead to substantial losses for most

investors in after-inflation and after-tax net worth, even if gold does rise

to $10,000 an ounce or higher with an effective collapse of the dollar. When we buy gold or silver with an informed

understanding of how precious metals perform during a time of severe economic

crisis – with simultaneous asset deflation and monetary inflation – then we

have the ability to potentially create wealth on a multigenerational

scale. Because during crisis, gold performs

best as an asset deflation play, rather than as a monetary inflation hedge, and

if we don’t see that, then we may miss the best precious metals investment strategy

of our lifetimes.

| Click Here To Learn About A Free Mini Course That Will Teach You How To Turn Inflation Into Wealth. |

Real estate is where things getcounterintuitive. Yes, even if

substantial real estate price deflation persists in real terms over the coming

years, we can still potentially reap rich rewards through real estate

investing. Indeed, the Federal Reserve has created an unprecedented opportunity for wealth creation through its

actions. However, these opportunities

are not based upon the simplistic real estate investment methods of maximizing

leverage that are so successful when bubbles are inflating, but can be deadly

during a time of ongoing asset deflation.

Rather, to make money as a bubble continues to deflate even while

markets are systemically manipulated, we must play monetary inflation off of

asset deflation, using a calculated and deliberate methodology, and in the

process, create wealth in a risk-reduced and tax-advantaged manner.

Simply put, what we have reviewed in

this article creates a situation of enormous potential volatility. The pressure may be released at almost any

time, and in the process lead to a massive redistribution of wealth that

devastates most people, pension funds and governments. Conversely individuals can take personal

action to position themselves so that they benefit from this redistribution. The difference between individual peril and opportunity

is one of vision – and education.

Would

you like to find practical solutions to the issues raised in this article? Find out how to position yourself to

benefit from what happens when political decisions place the value of the

dollar at risk? Do you want to know how to Turn

Inflation Into Wealth? To

position yourself so that inflation will redistribute real wealth to you, and

the higher the rate of inflation – the more your after-inflation net worth

grows? Do you know how to achieve these

gains on a long-term and tax-advantaged basis?

These are among the many topics covered in the free “Turning

Inflation Into Wealth” Mini-Course.

Starting simple, this course delivers a series of 10-15 minute

readings, with each reading building on the knowledge and information contained

in previous readings. More information

on the course is available at DanielAmerman.com or InflationIntoWealth.com .

Contact Information:

Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Website: http://danielamerman.com/

E-mail: mail@the-great-retirement-experiment.com

This article contains the ideas and

opinions of the author. It is a conceptual exploration of financial

and general economic principles. As with any financial

discussion of the future, there cannot be any absolute certainty. What

this article does not contain is specific investment, legal, tax or any other

form of professional advice. If specific advice is

needed, it should be sought from an appropriate professional. Any

liability, responsibility or warranty for the results of the application of

principles contained in the article, website, readings, videos, DVDs, books and

related materials, either directly or indirectly, are expressly disclaimed

by the author.

Copyright 2010 by Daniel Amerman