Reading One:

Inflation Pickpocket

Inflation is not an even game, it is not a fair game, and we are not all in this boat together. For inflation is not about destroying everyone’s wealth – it is about redistributing that wealth. If you don’t understand the specifics, then it will likely be your wealth that will be getting redistributed.

To illustrate how inflation redistributes wealth, we will use a simple morality play with two investors, in three acts.

ACT ONE: Smooth Economic Sailing

Peter is our virtuous hero, for he understands that a penny saved is a penny earned. Peter has been diligently saving for retirement, and that saving has taken two forms. The first was paying down all his debts, and the second was building up retirement assets. So Peter contributed to society through his work, was paid for his contributions, controlled his spending, responsibly deferred his gratification, and built up $100,000 in hard-earned savings.

Scott is our irresponsible villain. Scott is not the kind of guy who appreciates the wisdom of being debt-free. Indeed, Scott doesn’t assign any moral implications to how he manages his money at all. Scott has a use for $100,000, he sees that Peter has the money ready for investment, so Scott borrows $100,000 from Peter.

So, virtuous Peter has a $100,000 asset with no debt, and irresponsible Scott has a $100,000 debt.

(Both hero and villain happen to be Baby Boomers, for there are aspects of this play that are particularly appropriate for investors of the Boomer generation. However, the lessons apply to all investors, and indeed, some aspects are even more applicable for many investors outside the United States than they are for American investors.)

ACT TWO: Picking The Pocket

The Chinese and Japanese finally stop buying US treasury bonds altogether (and thereby stop supporting the dollar), forcing the Federal Reserve to continue to create trillions of dollars from thin air to “fund” the US government. The Boomers are retiring in increasing numbers and are increasingly trying to convert their bountiful paper wealth supply of dollar-denominated investments into a quite limited supply of real goods and services, even as government deficits reach all new levels in attempting to pay for the ongoing Bailouts, Stimulus packages, Social Security and Medicare. The US scrambles to simultaneously find buyers for the Boomers' securities, mortgages, corporate and government bonds, as well as hard currency to buy oil from exporters that will no longer accept dollars. (A concise description of some complex issues, but this is a short play and illustration, not an econometric model.)

The dollar drops 90%.

The former dollar is now only worth ten cents. What you used to be able to buy for $1 now costs $10. Whichever way you care to look at it, 90% of the former value of the dollar is gone. And so is 90% of the value of the debt which Scott owes Peter.

In real (inflation-adjusted) terms, the $100,000 investment that constituted Peter’s loan to Scott is now only worth $10,000. So Peter has lost $90,000 of his investment, in purchasing power terms. Scott, on the other hand, no longer owes $100,000 in real terms. He only owes $10,000 in inflation-adjusted terms, meaning his personal purchasing power is $90,000 ahead in real terms of where he started (or $900,000 ahead of where he was in nominal terms, keeping in mind that it now takes a dollar to buy what ten cents used to).

By borrowing $100,000 in pre-inflationary dollars, and paying back (in full) $100,000 in post-inflationary dollars, Scott has used inflation to redistribute $90,000 in real wealth out of Peter’s net worth, and into his own net worth. By better understanding that inflation destroys debts even as it destroys dollar assets, Scott has used inflation to take $90,000 directly from the virtuous and cautious Peter, just as effectively as if he had picked Peter’s pocket.

ACT THREE: Real Assets & Pieces of the Pie

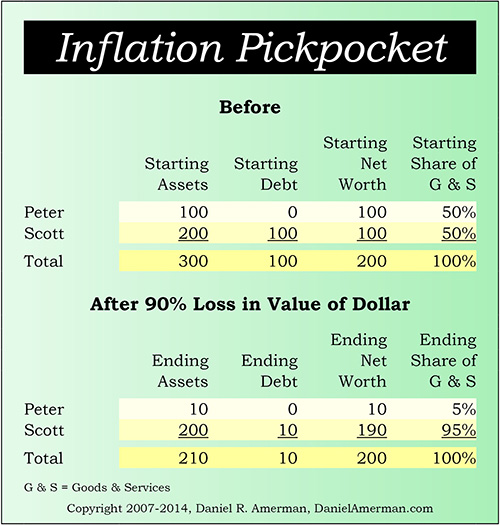

To more fully understand what happened and how Peter was separated from his net worth, let’s take a closer look at our “villain”, Scott, and the chart below. Like everyone else who knows how to read a newspaper, Scott was aware that the federal government was spending dollars it did not have with complete abandon. He could clearly see that the pretense was being dropped in terms of tax revenues being sufficient to pay for government bailouts and promises, and that this was leading to an impossible debt load. Scott was further aware that the easiest way for the government to renege on its debts was to inflate the currency. Inflation allows a nation (or corporation or individual) to legally pay in full in contractual terms what has been promised, but those payments become worth only a small fraction of what the original debt was.

Scott was in fact just as responsible a saver as Peter, which is how he built his own $100,000 in savings. Because he saw inflation coming, unlike Peter, Scott put his savings into solid, real assets of the sort that withstand inflation (such as cash flow producing properties, precious metals and other contrarian assets). Because Scott understood economics, he was happy to take Peter’s loan as well, particularly at an interest rate that was only slightly above the then low rate of inflation. Scott took that money, and purchased another $100,000 of hard assets. Scott’s pre-inflation combined position was $200,000 in real assets, and $100,000 in dollar debts, for a net worth of $100,000.

Scott further understood that, ultimately, dollars are mere symbols and resources are reality. He understood that what he needed in retirement wasn’t actually electronic symbols in a brokerage statement -- but the right to convert his savings into goods and services so that he would be able to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle. So Scott prepared the chart below:

As can be seen above, Peter and Scott each start with an equal net worth, and an equal claim on goods and services, meaning that each has an equal right to goods and services in retirement. The ending bottom line, however, is Scott owns 95% of the rights to the goods and services, and Peter only owns 5%. So Peter spends his 70s cleaning tables at a fast food restaurant, while Scott enjoys a verandah suite on frequent cruises.

And the most nefarious part of this little confidence scheme? The mark never even realized what happened to him, because Scott repaid Peter in full, as contractually promised. While sweeping floors, Peter frequently shook his head about the irony of his having made a successful investment in a time of financial chaos, an investment that paid him back in full, and yet he now found himself impoverished by the same inflation that claimed the retirement assets of nearly all of his friends. It never occurred to Peter that Scott had quite deliberately used inflation to take $90,000 of that net worth.

A Deliberately Offensive Story

What a horrible ending to a perfectly lousy story! The virtuous and debt-free hero makes a good investment that is repaid in full, but still must spend his golden years cleaning up after teenagers. Meanwhile the villain is cruising around the world as a reward for his fiscal irresponsibility. If you are feeling a bit outraged and perhaps even offended by the way the story is presented and how it turns out – good! For that means you are learning a crucial yet little understood lesson about inflation right now by reading an article, instead of learning it by losing much of your net worth in the future.

For good reason, there is an enormously powerful paradigm with which many of us were raised, this morality play that says that "savings are good and debt is bad". These are heartland values, of the kind I was raised with as well, and there is powerful truth to them in ordinary circumstances. However, there are some unspoken assumptions underlying this view of savings and debt: 1) that the currency is stable; 2) that assets and debts each maintain their value; and 3) that a dollar is a dollar. The problem comes when these assumptions are incorrect. With powerful inflation, what a dollar is worth changes every year (and every month), and that turns our morality play upside down.

The problem is that most of us want to be the “mark” in the little three act play above. We want to be debt-free, particularly coming into retirement. We want to have substantial portfolios of stocks and bonds, just like nearly all of the financial columnists preach. We want to be responsible, to pay as little money as possible in debt service – so that our financial assets are working for us, instead of us working for our creditors. These are good, solid truths – but they all add up to being like Peter and having the maximum possible exposure to losing the value of our dollar-denominated savings if major inflation does occur, with no hedge or portfolio insurance to protect us, and with no ability to even partially offset those losses through profiting from the inflation driven destruction of the value of our debts. We have a burning desire to walk down dark alleyways with 20 dollar bills hanging from every pocket. Which is exactly what we will be doing if major inflation returns, and there are compelling reasons to believe that it will.

Changing The Names

“Peter” and “Scott” were used to make the play personal, and this play is hopefully something the reader can more easily relate to than abstract economic principles. The story could happen just the way shown, with one individual making a loan to another. However, it is far more likely in today’s world that the financial “system” will be standing between Peter and Scott. For instance, Peter could be investing in bonds, and Scott could be borrowing via a home mortgage (the historical way in which millions of “Scotts” made a great deal of money the last time inflation rampaged in the 1970s, at the same time that the stock and bond investing “Peters” of the world were getting badly burned). Taken together, however, the picking of the pockets will work the same basic way for the Peters and Scotts of the world, even if their transactions are not directly with each other.

When we remove the direct personal component then, does this change your view of the comparative morality? Is Scott being somehow a bit shady when he accepts the terms of a loan that is freely offered from a large and sophisticated financial institution that is in the business of lending? If Scott accepts the loan because he has a five or ten year horizon, while the executives at that bailed out financial institution are only looking to the next quarter or year – is that indicative of a shortcoming on Scott’s part? Or does that merely mean that Scott is intelligently looking after his own self-interests?

The Redistribution Of Wealth

This principle of the redistribution of wealth is both one of the central elements of economic history – and almost entirely outside of the way that long term financial planning is usually presented.

The naïve version, as commonly presented in the media, is that inflation hurts all of us, and the best thing we can try to do is to outrun it through choosing the right investments. As we will cover in the readings ahead – trying to outrun inflation with traditional investments is a very difficult thing to do, and becomes near impossible for most people when we consider tax consequences (the subject of the next reading).

This naïve version is unfortunate, because we have a very long history of nations experiencing high rates of inflation, and we know how that tends to work out. The primary victims of inflation tend to be the older part of the population, and the primary beneficiaries are the younger people. In other words, if you’ve been working for decades to build financial security, history shows that your financial security is the natural victim of inflation. And this devastation of their retirement portfolios is something that most of the population can’t outrun, almost by definition.

However, when we step outside the conventional financial box altogether, and consider that for every Peter – there is also a Scott - then a quite different approach opens up for us all.

Can we become Scott instead of Peter in a risk-reduced and tax-advantaged manner?

Can we get out of step with the rest of our generation?

Can we fundamentally change our financial profile so that basic, powerful economic forces naturally work to turn the destruction of the dollar to our benefit, instead of destroying what we have built?

Can we use an informed understanding of these principles to potentially radically improve the performance of such traditional inflation hedges as precious metals and real estate, reducing overall risk while increasing after-tax and after-inflation gains?

Welcome to the Turning Inflation Into Wealth Mini-Course! If you found that this reading challenged some of the very basics of what you’ve believed to be true about inflation and financial security, then good, it’s doing exactly what it was supposed to do.

From the letters I've received, I also know that there is a tremendous temptation to immediately try to place what you've read into a "box", where it can be safely classified.

Resist the temptation!

First and foremost – this is a course in solutions. We will introduce a quite different set of solutions than those traditionally found in personal finance. Solutions that simultaneously draw upon the root fundamentals of finance and economics, as well as strategies that are employed by some of the most sophisticated professional investors in the world.

To get to those individual solutions requires a process of paradigm change for most people, so they can learn to see personal financial challenges and personal financial security from a quite different viewpoint.

What you just read was an "eye-opener" that was intended to get you thinking, and the next reading is an equally fundamental eye-opener that covers a quite different topic.

More About Debt

A few readers have misinterpreted this reading as preaching the wonderful virtues of going into debt. This is not the case, however, because debt isn’t always good. As commonly used – debt can be toxic. The subprime mortgage debacle is just one example of how too much debt can destroy people. Indeed, the next time that powerful inflation hits, it can be safely predicted that being in the wrong kinds and amounts of debts will devastate millions of households, whether it is their credit cards, variable rate mortgages, or both.

No, one of the main points of our little “morality tale” is to illustrate the dangers of oversimplification. For instance, a simple approach is that if you want financial safety, then financial assets are always good and debts are always bad. It's a quite common approach, but as illustrated with Peter – the results of this simplistic approach will be absolutely devastating for tens of millions of retirees if inflation is to be how Boomer retirement promises and Bailouts without limit are finally paid.

If A Friend Sent You This Link

If you found this reading because of a friend’s recommendation, then you should know that it is part of a free book on Turning Inflation Into Wealth. Sign-up below if you would like your own copy of this valuable educational resource, delivered via e-mail.

If there is something in this reading that you think a friend or colleague would find helpful, you are encouraged to send them a link to this webpage.

Please DO NOT use the form above to sign up friends without their permission. The book is intended only for people who want it, and have given their permission by signing up for it.

All readings in the book are the exclusive property of Daniel R. Amerman, CFA. Subscribers are allowed to print a single copy for their own usage. Any other copying of materials from these readings and reposting or reprinting elsewhere is strictly prohibited and constitutes a violation of international copyright law. If you would like to share these educational materials with others - please use a link to this website.