Japan Crisis Triggers Three Categories Of US & Global Inflation

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Overview

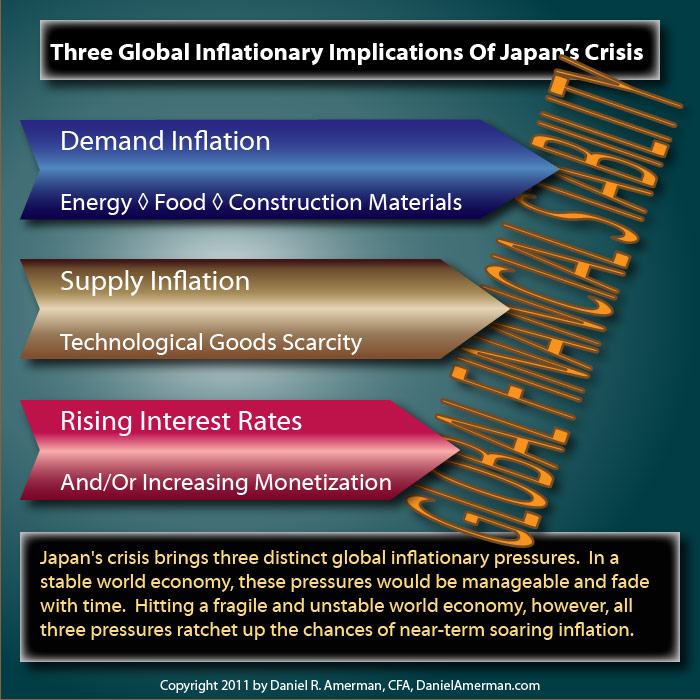

The triple tragedy of earthquake, tsunami and nuclear crisis in Japan may have global consequences that go well beyond atmospheric radiation. Three distinct categories of inflationary pressures have been created: 1) Demand Inflation pressures; 2) Supply Inflation pressures; and 3) Interest-Rate pressures that could lead to increased global monetization.

The chart below summarizes these three pressures, which we will briefly explore, along with the consequences for the purchasing power of the US dollar and global consumer standards of living.

The inflationary pressures shown above are each significant, but they are generally short and medium term problems that would not likely have major long-term consequences outside of Japan if the global economy were in a stable position. However, the current global financial situation is anything but stable, and the greater danger is that the pressures shown may both individually and as a group act as "triggers" that ratchet up the chances of near term global financial meltdown.

Demand Inflation

The first category is that of demand-based inflation. Demand inflation occurs when the prices for goods rise because of an increased demand for those goods. There are three broad categories in which we can expect rising demand in the international marketplace for some of the fundamental raw materials of life, as a result of the crisis. This increased demand - and the Japanese using their still powerful financial position to outbid other nations for the already limited supply of these products - is likely to cause rising global prices.

(For this article, we are viewing inflation from the perspective of international markets, increases in supply or demand for those markets, and how this all affects individuals outside of Japan. On a domestic basis, decreased internal supplies of energy and food that must be replaced with expensive international purchases means supply-based inflation for the Japanese themselves.)

The most prominent component of demand inflation is that of energy needs. The headlines have been full of the tragic events at Japan's Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex, and Japan as a whole is currently short of about 20 to 40% of the energy that it needs to run the country, according to press estimates. Not only are the nuclear power plants shut down in the affected part of the country, but there has also been substantial damage to many conventional power generators. Daily life in Northern Japan and Tokyo includes a series of rolling blackouts, even as overall energy usage is reduced during this part of the crisis.

To replace lost capacity, Japan is going to have to purchase more oil and gas on the international markets. While Japan is already making advance purchases, we haven't yet seen the full impact of this purchasing program, because Japanese energy consumption is currently down due to so many conventional power generation facilities - along with the nuclear facilities - being closed. As these conventional power facilities reopen, we know Japan's energy imports will be rising over the coming months.

In a world in which the price of oil is already over $120 a barrel due to long-term rising demand, and with multiple current and potential crises in the Middle East, Japan's fundamental-based increase in demand for the energy that it must purchase from the international marketplace is likely to significantly affect global energy prices, possibly making them that much higher. Thus, wherever you are in the world, you are likely to pay more money to fill the tank in your car, or to heat or air condition your house.

Another broad area of concern is that of food prices. Per a United Nations index, food prices around the world have already been rising to record levels in recent times, even before the crisis in Japan. Now, because of the substantial degree of farmland resources that are affected by growing radiation levels, with perhaps even an impact on nearby ocean resources as a result of the radiation leaks, Japan must increasingly turn to the international markets to meet its food needs.

Food prices were already at "dangerous levels" according to World Bank President Robert Zoellick, with about 900 million people going hungry each day. Recent drastic rising prices for staples such as rice, corn and wheat have led to riots in developing nations. While it might not appear that the increase in demand in Japan by itself is enough to be of major importance, keep in mind that this is all occurring on the margin. A condition of global scarcity and rising prices already exists, and now global demand has just risen. As a wealthy nation. Japan will buy this food, and the rest of the world will be scrambling with less food available to meet the overwhelming demand that is already there. This situation can be expected to lead to further increases in the cost of groceries for all of us.

The third area of demand inflation is the demand for raw materials for reconstruction. Japan faces a massive project in terms of the rebuilding of damaged cities, provinces, housing infrastructure and factories, and this is going to require the purchase of large amounts of construction raw materials from the global marketplace. These raw materials include such items as steel, concrete and wood.

Even before Japan's tragedy, as with food and energy, global raw material prices for such resources as steel had already been rising because of increasing global demand from countries such as China. As an example, as China continues to purchase steel to build its own infrastructure, even as Japan rebuilds its damaged infrastructure (whether the factories are rebuilt in Japan or outside of Japan is a different matter), there will be mounting price pressures on steel - which are already up to over $900 a ton (world composite steel price), or about a 25% increase in the first quarter of 2011 alone. Price pressures will also be growing on wood, concrete and copper, as well as on other commodities. The cost of building new homes and highways goes up across the globe, as do the costs of other products using the same materials, such as paper and furniture for wood, and steel for cars.

Supply Inflation

A distinctly different type of inflation is the result not of an increase in demand, but a decrease in supply. When this decrease in supply means that demands can't be met - the new scarcity creates rising prices.

We are already seeing this inflationary effect with US auto prices. Within a week or so of the crisis, Japanese automakers in the United States were dropping discounts and special incentive offers. This could easily add $500 to $2,000 or more that US consumers are paying when they buy a Japanese car (whether that car is actually made for the most part in the United States or Japan).

The issue is that not only do the major Japanese automakers – as well as other major Japanese corporations – have a number of manufacturing facilities in the affected areas in Japan, but so do their contractors, and so do the subcontractors for the contractors. All it takes to shut the whole operation down is one subcontractor supplying a key part that cannot be easily or quickly replaced elsewhere - and that subcontractor's production being directly affected by the earthquake or tsunami, or substantively reduced by the rolling blackouts in Japan.

This then leads to a shortage of the product whether the shortage has reached the markets yet or not. There are already ongoing discussions of closing various facilities in the US until the supply chain can be reestablished. Ironically, the first related closure in the US was of a General Motors plant in Marion, Louisiana rather than a Japanese automaker.

Nobody yet knows just how wide this will spread; it all depends on the particular companies and industries. Toyota, Honda, Subaru, Volvo, Sony, Canon, Fujitsu and Tokyo Electron (world's second largest maker of semiconductor equipment) are among those affected. In general, to the extent that there is global dominance by Japan in some key technological areas – even if this dominance consists only of a relatively few but essential parts of a final product that may then be assembled in an entirely different country – then in technologically sophisticated goods around the world, we can expect supply chain problems in Japan to spread out and create increasing shortages of these goods. Supply shortages which then translate straight into rising prices as scarcity takes effect.

Rising Interest Rates & Increased Monetization

As Japan's exports fall and Japan's imports rise - at least in the short and medium term - this means that Japan is taking in less excess US dollars and euros than it normally takes in as a result of running a substantial trade surplus with its trading partners. In order to hold down the value of the yen, the Japanese government has often recycled these trade surpluses into purchases of assets such as US treasury bonds. On a short and possibly medium term basis, it appears that Japan will be having fewer excess US dollars to be invested in treasury bonds. This means the US dollar and the US treasury may have lost a substantial supplier of investment capital. The US is running up record deficits and now, on a fundamental basis, the (historically) largest foreign buyer is now likely to be reducing its funding of US deficit spending. On a market basis, what we would expect is that absent any other changes, interest rates must rise to bring new buyers into the market.

As covered in previous articles, a rise in US treasury borrowing costs more or less instantly goes out through the entire economy, and translates to increases in interest rates for credit cards, for auto loans, for mortgages, and for corporate and municipal borrowing cost. Hitting an already wounded US economy, this rise in interest rates could cut off any incipient economic recoveries, while increasing the budget deficits faced by troubled state and local governments.

This would be a major issue indeed if the Federal Reserve were not already creating money on a massive basis to fund its purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds. Given this situation, the loss of a major pillar of support for the US dollar and US treasury bonds is not likely to trigger free-market consequences, but rather an increase in monetization pressure. It may be that the most likely consequence if Japan reduces its purchases of US treasury bonds (and that's a big if), will be the US government being forced to ratchet up its creation of dollars out of thin air.

This situation also exists in Europe as it does in Japan itself. With a global economy already in crisis, and a shortage of funds to pay for expensive rescues on top of social promises, the loss of one of the world's major buyers of foreign debt just means there will be an increasing pressure upon bankrupt governments to manufacture currency on a global basis.

Potential For Triggering A Larger Economic Crisis

When we pull everything together, we have international demand-based inflation in the categories of food prices, energy prices and raw materials; we have international supply scarcity inflation affecting autos and other high technology Japanese exports; and we have a likely reduction in Japanese funding of other governments' deficits that is likely to lead to increased monetization pressures.

While these three categories of pressures are indeed of concern, by themselves they are not globally significant over the medium to long term, unless there were to be a Chernobyl-like release of radiation that would substantially reduce Japan's economic capacity.

Even if all six of the reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex were to be permanently closed, that is still less than 5% of total Japanese energy-producing capacity to be replaced in the short to medium term by oil and gas, and in the longer term likely by something else. Food shortages are significant, but Japan has much farmland that has not been affected (again, absent a larger radiation disaster) and Japan only has about 2% of the world's population. The total cost of rebuilding has been estimated at approximately $200 billion, and while that is significant, it is still less than one half of 1% of annual global GDP. With each passing day and week, ways are being found to resume production of the affected Japanese technological goods.

Without minimizing the enormous personal tragedy for the people involved, if the global economy were currently healthy – then absent a massive radiation release, the disaster in Japan would likely end up being a global economic history footnote. The three inflationary pressures would be there, they would affect the global economy for a year or two, and then they would effectively fade away.

However, the US dollar and the euro are already fundamentally in deep trouble, as the United States and Europe are effectively bankrupt when we look at the costs of meeting future social promises and currently outstanding government debts, compared to realistic projections of future tax revenues. This is a fundamental instability that only needs a trigger to set it off, and we're already seeing that potential trigger even without the events in Japan, in terms of the impossible-to-ignore increases in food, energy and healthcare costs (even if these increasing prices seem to be mysteriously absent in the official rates of inflation).

The crisis in Japan on a fundamental level acts to increase prices for food, energy, raw materials and technological goods, and when combined these factors will likely decrease the purchasing power of the dollar. When we add in likely increased pressures to monetize, the result is an ever increasing amount of dollars meeting an ever decreasing supply of goods, and then we are truly looking at potentially explosive movements in the prices of goods per dollar.

This is unlikely to be an evenly felt process, however. Those people whose lifestyles are most heavily based upon either assets or incomes that won't move with inflation, are likely to experience a disproportionate reduction in their personal standard of living. On the other hand, people whose financial positions are structured such that they can at least partially neutralize the negative effects of inflation, or perhaps even benefit from it, are likely to experience something in the range between a lesser reduction in their personal standard of living and an outright increase in their standard of living.

Scarcity Of Goods, Abundance Of Dollars

All else being equal, inflation does not directly destroy the wealth of the nation or an individual, but rather redistributes the rights to that wealth among the citizens of the country. Unfortunately, sometimes everything else is not "equal", but rather, we face hard times.

The extraordinary hardship in Japan in personal terms is all too likely to translate to global issues with regard to economies, the purchasing power of money, and potentially the day to day standard of living for many people. With the destruction in Japan from the earthquake, tsunami, and resulting nuclear power plant radiation, there is now increased international market scarcity in the fundamental categories of energy, food, construction raw materials, and certain key technological products. There is less to go around, and that means that some people who would've had more of these things in the past will necessarily have fewer of them in the future, at least until recovery is complete.

However, there is one item that never seems to be in shortage these days, and it is all too likely that we'll see still more of it as a result of this fundamental scarcity in some of the essentials of life. That item is the supply of US dollars and European Union euros, as well as other currencies around the world. The scarcity-induced inflation shock in the US is all too likely, when combined with the hidden depression that the United States is already in, to lead to increasing pressures to monetize in the short term and try to smooth out the damages. This US government policy of creating dollars on a massive basis out of the nothingness, is unfortunately, a terrible tool to turn to when we're looking at sharply rising "natural" prices as a result of global changes leading to temporary scarcities. A combination of fewer real goods to go around even as ever more dollars are pumped into the economy to smooth it out, has potentially explosive implications for the purchasing power of those dollars.

This means that what would otherwise be a short term tragedy in one corner of the world that would be smoothed out with time, may have an entirely different effect – which is to act as a trigger for far larger inflationary pressures.

Let's return to the chart with which this article began. Look at the three arrows of inflationary pressures, and consider the already unstable situation. The greater danger is not the arrows themselves but the way each pressure point can act as a lever to potentially force a change in the bigger picture situation. The US dollar already faces tremendous dangers, and while we can't know for certain, the chances of the US dollar getting through this situation without a catastrophically high rate of inflation – and the resulting reduction in purchasing power for savers and investors who were relying on the value of their portfolios - is much reduced.

As you watch the ongoing headlines, think about the three categories of new pressures that have been brought upon the dollar, the possible consequences for your standard of living, and whether or not you are truly comfortable with your preparations for inflation.