How Social Security Trust Funds Will Change Private Retirement Income

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Below is the 2nd half of this article, and it begins where the 1st half which is carried on other websites left off. If you would prefer to read (or link) the article in single page form, the private one page version for subscribers can be found here:

Following The Money

No matter how complex they may seem, many financial deceptions can be unraveled by a basic process – just follow the money.

To see what is currently almost universally being missed about Social Security and other government retirement trust funds, we merely need to follow what is actually going on at four distinct points: 1) when the money comes in; 2) the years during which the money is "invested"; 3) the redemption of the principal due; and 4) the aftermath of the redemption.

1. When the Money Comes In

As the money comes in, it is immediately spent in full by the US government, either in payments to payroll tax beneficiaries or for general spending purposes. And the money which went for general spending is effectively replaced with an IOU, which is an obligation of the United States government to itself.

2. The "Investment" Of The Trust Funds

Over the decades that follow, interest is paid by the US government to itself on an ongoing basis.

However, this is a purely paper transaction and does not require spending any actual taxes or cash.

Instead, the Treasury looks at the interest that is due, and it effectively pays that interest in the form of new government bonds.

No new cash – just new IOUs, written to itself.

So over the years, the trust funds compound the amount of IOUs that the government owes to itself, with no economic reality in terms of actual cash or economic activity.

3. The Redemption Of The Bonds

This is perhaps the most fascinating part in following the money trail, given it is a complete inversion of what's being presented, and it is the least understood part.

The simple truth is that the government is not making principal and interest payments on its debt out of tax revenues – because it doesn't have the cash available to do so.

Instead, when principal payments come due, the government borrows the money to make those payments, and when interest payments come due, the government borrows the money to make those as well.

So when Social Security and other retirement fund programs are drawn down to make payments to beneficiaries, the government isn't actually using tax revenues to do that, but rather it is rolling over the debt, and borrowing to make the principal payments to pay off the trust funds.

Because one debt is being replaced by another debt, then at least at this first stage, this borrowing to pay off the Social Security trust fund does not by itself increase either the annual deficit or the level of federal debt outstanding. It is an invisible process if we are just looking at annual deficits or total debt outstanding.

However – and this is of absolutely crucial importance – this borrowing to pay down borrowings does over time substantially change the sources of funding for the federal debt.

Social Security and other government retirement funds are really just paper liabilities to a large extent because the government simply owes the money to itself, and no one else has to participate in terms of coming up with cash or agreeing on an interest-rate or so forth. The trust funds are a captive source of funds, with no negotiating power, that passively accept whatever the government does.

So as these retirement funds including Social Security get paid down, what happens is there is an ongoing rollover of principal from the private captive market of these trust funds, to bringing in actual real money from actual investors who want actual cash back.

As we go forward through time and these trust funds pay down, they don't on the surface increase the level of government debt. What they actually do instead is that over time they radically increase the amount of money that the US government must take in from external investors – in a manner that does not show up in the usual bottom line.

4. The Aftermath

While this change in funding from internal to external never appears in the annual deficit or total federal debt outstanding calculations – it is quite likely to have extraordinary implications that could last for years and decades to come.

The trust funds are captive because they can't invest anywhere else – they have to buy US government debt. They can't move to corporate bonds or stocks in the search for higher yields. They don't negotiate for the yield, and they must be content with accepting payment in paper. They have no choice but to passively accept payment in additional IOUs each time principal is paid and rolled over, and must accept payment in still more IOUs every time interest payments come due.

From the perspective of the US Treasury, then, Social Security and other government trust funds have arguably served as the "ideal investors" for many decades.

However – at least in theory – everything changes when $1 billion in bonds that were held in the Social Security trust funds are redeemed and the cash sent to beneficiaries, even as this is funded by selling $1 billion in Treasury bonds to external investors.

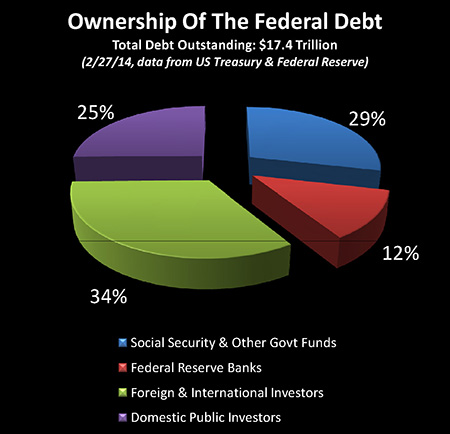

As can be seen above, Social Security and other government trust funds hold about 29% of the US federal debt outstanding. This is larger than total private investment in US Treasury obligations, and second only to the 34% lent to the US government by foreign and international investors.

So, if the US government is to borrow the money to pay off the bonds held in the government trust funds, then it is going to need a very great deal of new money, whether that money comes from banks, individuals or obliging foreign governments. There has to be a steady increase in demand for Treasuries that goes well beyond the stated annual deficit.

Now – supposedly – to bring these investors in, a market interest rate has to be paid. So the government has to compete against other investments on a risk/return basis, and may, in theory, have to increase interest rates, particularly if they need to more than double the size of their investor pool (not including foreign investors).

And this process is not a one-time event. The Treasury will need to go to outside investors again each time an interest payment comes due – because remember, the government doesn't have the money to make the interest payments. And indeed, most of the annual deficit consists of money borrowed to make interest payments on the national debt.

Each interest payment means that another new investor has to be found to come up with the cash to make the interest payment. Which is one of the big problems (from a governmental perspective) with moving from internal to external investors. For while the captive audience of government trust funds have no choice but to accept interest payments in the form of IOUs from the government, external investors expect cash.

And let's assume that the bond in the Social Security trust funds was cashed out by selling a short term bond to an external investor. (Per the GAO's 2013 audit of the federal debt, 58% of the Treasury debt held by the public will mature within four years.)

Each time that bond matures and needs to be paid off, it is (in theory) another potential exposure to the vagaries of markets and interest rates as yet another bond needs to be sold to come up with the cash to pay off the first one, potentially meaning another investor needing to be found.

This is an exposure that did not exist so long as the bond was held internally by a captive investor.

So when the "assets" in Social Security and the other trust funds are drawn down to make payments to beneficiaries, what is really happening is a steady – and massive – shifting of the US national debt from what are purely paper assets and paper interest payments into actual cash borrowing and actual cash interest payments, which also compound over time.

The Links Between Quantitative Easing & The Debt

The reason for qualifying certain points in the preceding section with such words as "in theory" and "supposedly" is that we haven't been in a true free market in recent years, nor have the debt rollovers all been going to true external investors. That hasn't been the case because the United States government has had a major partner and helper in recent years.

This partner and enabler has of course been the Federal Reserve with its program of quantitative easing, which is the creation of massive sums of money by the tens of billions of dollars every month out of the nothingness that are not spent by the government in the general economy – but are instead currently used to purchase Treasury obligations and mortgage-backed securities.

The Federal Reserve has purchased more than $2 trillion in federal debt, and that means that about 12% of the currently outstanding federal debt did not need to be funded by private investors or by foreign governments.

Of even greater importance is that it is the purchase of those bonds and mortgage-backed securities that has kept interest rates so low for US government borrowings, as well as supported the real estate market through making housing much more affordable for home buyers (even while slashing bond and money market returns for many millions of savers and investors).

Quantitative easing has thus served a dual purpose, with the first being to effectively fund a big portion of the rollovers of federal debt outstanding, as well as new deficit spending. And by doing it through the secondary market rather than buying it direct from the U.S. Treasury, quantitative easing has served its second and even more important purpose of allowing the Federal Reserve to take full control of interest rates in the United States on a national basis.

Now the Federal Reserve has been discussing winding the program down over time and letting the markets return to a more natural state.

If as discussed the Fed does indeed continue to taper the level of quantitative easing and end it altogether by the end of 2014, then there'll be a very gradual reduction in its balance sheet as that debt is paid down rather than rolled over internally within the Fed. This means that just as with Social Security – the US government must find new sources of funding who are willing to purchase those trillions of dollars in debt and replace the Federal Reserve as the investor – except at market prices and interest rates.

Five Levels Of Pressure

If we accept the Federal Reserve's claim that it does indeed plan to end quantitative easing as soon as economic conditions allow (which supposedly is any time now), then this sets up five levels of pressure when it comes to securing funding from genuine external investors, whether they be private investors or foreign governments. This funding needed from outside sources includes:

1. Investors to finance general governmental deficit spending, with increasing amounts needed as the Boomers age and retirement obligations increase.

2. Investors to finance the rollovers of the existing US debt held by external investors.

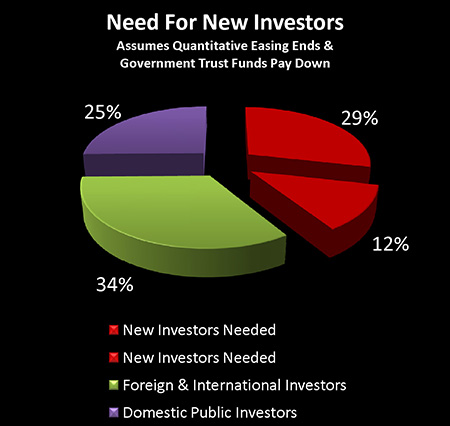

3. Investors to finance the rollovers of the 29% of US debt currently held in Social Security and other government trust funds, as the balances of these funds are drawn down.

4. Investors to finance the rollovers of the 12% of US debt currently held by the Federal Reserve, as quantitative easing is ended and the investments pay down.

5. Investors to finance the cash needed to make interest payments on all US debt held by external investors (unlike 2-4 above, this is a deficit item, as it does increase the national debt).

If we add 3 & 4 together, and they occur side by side, this would mean that an extraordinary 41% – or more than $7 trillion – of the $17.4 trillion in current federal debt outstanding would need to find new investors. This is equal to 164% of the just over $4 trillion of federal debt that is not currently funded by the government through its trust funds, or by the Fed, or by foreign investors.

The Link With Interest Rates

If we follow this potential scenario of the Federal Reserve phasing out its bond purchase program, even while federal deficits continue without end, even while the Social Security trust funds are steadily drawn down over the coming years to pay Social Security recipients, then these five levels of external borrowing must be funded from somewhere else.

And generally speaking, if the Federal Reserve has simultaneously released much of its control over interest rates voluntarily through ending quantitative easing, then there is a chance that interest rates will rise significantly.

Which would mean that the US government must find extraordinarily large new sources of funds every month of every year, and potentially at significantly higher interest rates than it is currently paying.

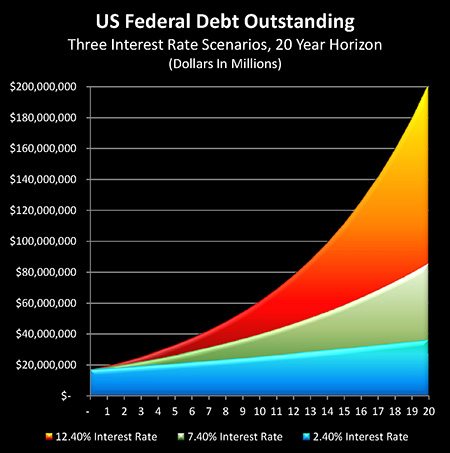

Now because all the interest payments are themselves being borrowed, then as covered in my article "Could A Compound Interest Wildfire Threaten US Solvency?", linked below, there is the danger of setting off a compounded interest and debt nightmare scenario for the US government.

http://danielamerman.com/articles/2014/CompoundC.html

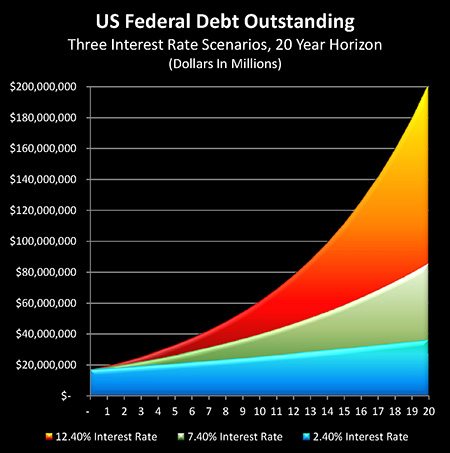

As illustrated in the graph, the payment of higher interest rates that must be borrowed can quickly and spectacularly explode out of control.

Integrating The Information For Investment Value

The two graphs below are explosive in combination, and are sufficient by themselves to invalidate the assumptions underlying most long-term savings and investment strategies.

If Social Security and other government trust funds are drawn down to make payments to beneficiaries even as quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve is wound down, then an extraordinary number of new investors in federal government debt must be found in the years ahead.

And if this scenario of rapidly increasing sales of US securities occurs in a rising interest-rate environment (because of the need to attract new investors), even as the Federal Reserve supposedly allows interest rates to return to market control, then in any given year there is the danger that things could flash over into essentially a financial Armageddon scenario.

So what does that tell us about the future and investments?

Well, first it tells us that the federal government will do absolutely everything in its power to keep financial disasters from happening – and it's best to keep in mind that no aspect of current law is likely to be reliable if and when push truly comes down to shove.

The way governments in the past have met these needs for massive amounts of below-market financing is they have essentially taken it from their own citizens and private investors.

Creating a decades-long environment of below-market interest rates and essentially forced savings in one form or another, even if there's no law openly passed that ever made that the case.

This was indeed the case in the US throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the last time the government was paying down a massive debt, and it has been true ever since at least 2010 as well, with pervasive Financial Repression (read more about Financial Repression here).

Now the heart of the challenge is, how does someone prepare for this financial environment in which the government changes everything it needs to – including laws, tax shelters (i.e. retirement accounts), interest rates, investment markets and the nature of money itself, all for a period of decades – in order to protect itself from potential financial disaster?

Mainstream finance does not have any good answers – because what is shown herein conflicts with and invalidates the very foundations of "modern investment theory". Most of what the public has been taught to be true about investments is based upon Modern Portfolio Theory, which is based upon mathematical models which are themselves based upon certain core, simplifying assumptions.

The central core of these assumptions – and the theoretical base upon which conventional investment strategies are built – is that investment prices and yields are necessarily determined in free markets by rational investors acting in their own self-interests.

Remove that assumption – and everything collapses. The elaborate investment theory developed in the academic financial world of the latter 20th century simply can't handle a pervasive environment of governmental interventions determining prices and yields, particularly when the motivation of the government will more often than not be to redistribute investor wealth to the government, in a manner sufficiently complex that the public won't understand what is happening.

Crucially, what has been demonstrated in this article is that the heavily-indebted US government faces an existential threat from a free market in Treasury bonds and interest rates over the coming decades, as it must replace its current captive sources of funds with external sources.

Therefore, the US government (and other heavily-indebted governments with aging populations) has overwhelming incentives to make sure there is no free market in bonds and interest rates.

Which means the government has an overwhelming incentive to deliberately override and invalidate the core assumptions underlying most private investment strategies.

This situation is both deeply ironic – and tragic.

Given that the financial reality of the trust funds underlying public retirement systems are indeed the "photographic negative" of what the public has been told, the government has extraordinary incentives to invalidate the likely future performance of the private investments which so many people have been buying in order to protect themselves, often specifically because they know the problems with the public system.

And since the financial crisis of 2008, governmental interventions have profoundly changed not only bond prices and yields – but as we've seen in recent years and are likely to continue to see in the years to come, they've also been a dominant determinant of equity, real estate and precious metals prices as well.

Perhaps the best way to prepare for the future is to fully understand what's actually happening in the present and recent past.

So when considering investment strategies, the best approach is to take a holistic and realistic look at the various challenges that are faced by the government, and the actions it will take to prevent disaster, with those future government actions quite possibly being the dominant determinant of future investment performance across all major categories.

It is only by doing so that one can gain the ability to position oneself to benefit from this environment rather than gradually falling victim to it. And that means a willingness to take a quite nonconventional approach when it comes to picking investment strategies for the future, with choices that are likely to be radically different from the traditional investment strategies of the late 20th century.