Quantitative Easing Reality Check

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Quantitative easing (QE) has not ended in the United States, but rather its growth has stopped, for at least a time. As of December of 2014 with the end of the "Taper", total Federal Reserve assets were about $4.5 trillion, and about $4.2 trillion consisted of US Treasury Securities and mortgage-backed securities – almost all of which were acquired as part of quantitative easing. These assets are not being allowed to decrease with time, but are being replaced as they mature. Meanwhile, QE continues at full speed in other nations.

The widely-accepted narrative is that quantitative easing, a.k.a. "cheap money", exists for the purpose of stimulating economic growth and corporate profits, and is thereby helping the United States and other nations that are struggling with persistent and deep-rooted economic and unemployment problems. If this were the whole truth, then QE is a temporary and technical fix, a mere "accommodative policy" that can be stepped down and then eliminated altogether once markets improve and economies no longer need assistance.

While there may be partial truth to this narrative, it is also dangerously misleading, because the primary purpose behind the strategy is something else altogether: quantitative easing started as and remains a defensive attempt to prevent what could otherwise very quickly become an annihilation scenario for global financial markets.

Quantitative easing started revolutionizing the US financial markets in 2008 (QE1), with the emergency creation of more than hundreds of billions of dollars in new money out of the nothingness to stop an institutional bank run already in progress, that was within days or weeks of annihilating both Wall Street and the European banking system.

Today, the core underlying problems of "Too-Big-To-Fail" banks – which face a toxic three way combination of counterparty risk, contagion risk and liquidity risk – are larger than ever. Because heavily indebted sovereign nations lack the financial resources to handle another crisis by way of conventional bail-outs, this creation of unlimited amounts of artificial money – in a manner that is independent of both taxes and budgets – remains the bulwark, and the primary line of defense against existential threats to global financial markets.

Quantitative easing is currently a primary determinant of stock and bond market valuations and investor returns on a global basis. Therefore, an informed understanding of its central role in driving prices and returns is of crucial importance to investors. And those who lack this understanding of reality will likely be making investment decisions across all markets that are likely based on "bad information".

To better understand, then, we will explore the underlying reasons for why quantitative easing came into existence, starting with QE1, which was followed by the rules-changing QE2, which was then followed by the most aggressive variant to date, that of QE3.

Stopping The Bank Run That Would Have Annihilated Wall Street

QE1 was introduced by the Federal Reserve in October of 2008 in order to prevent a collapse of the global financial system that was already in process. Indeed, if it weren't for quantitative easing, the world would've seen the quick collapse of Wall Street, major European banks, and most likely the global financial order as a whole.

There were three intertwined dangers that threatened to bring collapse within a matter of days or weeks, which have been described by the International Monetary Fund as being counterparty risk, contagion risk, and most important of all – liquidity risk.

The basic problem was that Wall Street had been having a party, creating huge derivatives contracts that couldn't be honored, while large bonuses were passed out to investment bankers.

But the party ended with the looming potential insolvency of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which because of credit derivatives exposures by Wall Street firms, could have taken down the financial system in a matter of days. So when the federal government stepped in to bail out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in September 2008, arguably the primary beneficiaries were in fact the Wall Street firms.

And when Lehman was allowed to go under rather than being rescued, this created the possibility of huge counterparty risk exposures when it came to all the investment banks and related institutional firms. The inability of Lehman to honor its promises meant that each counterparty that had entered into a derivatives contract with Lehman was at risk of nonpayment, which created an acute danger of cascading failures in the vast network of interwoven derivatives promises, in what could rapidly become an annihilation scenario.

This in turn created an environment of what the IMF refers to as contagion, or panic, where everyone was afraid to sell assets, because if they were to establish new market values on these large holdings of subprime mortgage derivatives and many other types of risky investments, all of Wall Street – along with many European banks – would have become insolvent.

Making the problem far worse, and the immediate source of the global meltdown risk, was liquidity risk.

Now Wall Street is based on the principle of OPM, otherwise known as Other People's Money. That is, for the most part those enormous profits and personal bonuses are earned by borrowing money from people and other firms, taking risks with their money, and then keeping most of the profits when the risks pay off.

And with contagion and counterparty risk spreading around much of the world, the financial institutions who had been loaning this money to the highly leveraged Wall Street decided they wanted their money back – and they wanted it back immediately.

October of 2008 was, then, in relatively pure form, the institutional version of an old fashioned bank run.

In a classic bank run, a bank makes a big investment that goes bad. Rumors of the loss spread to depositors. A long line forms, as worried depositors insist on withdrawing every cent of their deposits, immediately. But the bank doesn't have the money, as most of it is tied up in loans. So depositors are paid until the cash runs out, the doors close, and what seemed for all the world to be the safest, most prestigious and wealthiest business in town in the morning, is bankrupt and closed for good before the business day ends.

This familiar scenario happened over and over again during the decades and centuries before deposit insurance was introduced – and it was happening again in 2008 on the largest scale the world had ever seen.

Wall Street creditors wanted their money back. Wall Street didn't have the money to pay them, and if they were to sell risky and illiquid underwater assets as a group to get the money to pay back their creditors, this would have created "fire sale" prices on all of the investments, driving prices down that much further, and essentially creating a financial annihilation scenario.

And under the rules as they existed at that time – there was simply no way out. An institutional bank run was in process, the financial world was melting down, and there was no money to fix the problem.

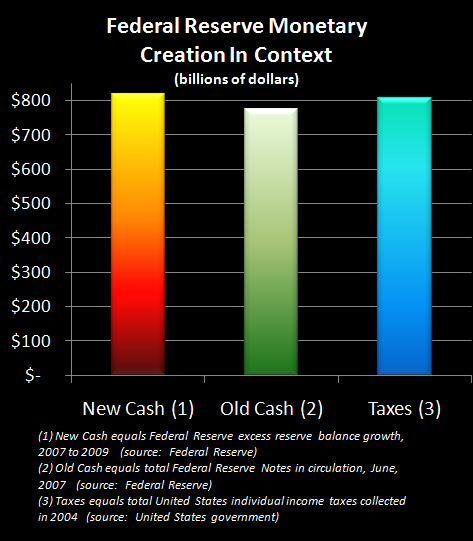

So the Fed radically changed the rules for what money is and how it is created with the introduction of Quantitative Easing One. As explained in my article, "Creating Trillions Out Of Thin Air" (linked below), through the use of excess asset reserves, the Federal Reserve created more money out of thin air between 2007 and 2009 than all the cash that was in circulation in the United States after 200 years of national existence.

http://danielamerman.com/articles/Trillions.htm

This $819 billion was not funded by taxes, nor was it a matter of spending by the US government. Instead, it was plain and simply the creation of money on a fantastic scale to get Wall Street and the global banking system out of the existential risk they were facing. A flood of newly created money was loaned by the Fed to various US and foreign financial institutions, with the banks then using this new money to pay their creditors. Thus a global bank run was stopped in its tracks, in such a way that kept effectively insolvent institutions viable – with no explicit bail-out being necessary.

The general public never quite understood this, nor just how close the financial world had come to annihilation – and likely global depression.

And this lack of understanding is what made it possible to sell the myth of so-called "weak banks" and "strong banks".

There were no "strong banks". Indeed, the so-called "strong banks" survived only because the Federal Reserve created vast sums out of the nothingness and loaned this money to them to prevent their near immediate insolvency. Absent quantitative easing, it was game over for the financial system.

This convenient myth persisted, however, and helped enable the payment of near record bonuses to Wall Street investment bankers in the following year – because there was no overt rescue that the public understood.

QE3: Averting Three-Way Disaster

Quantitative easing effectively redistributes wealth from households to corporations, thereby increasing corporate profits, which is part of the reason for the rally in the stock markets. Through effective currency warfare, QE also has at least the desired intent of lowering the cost of domestic production, thereby increasing exports while reducing imports, with the goal of boosting employment.

But the main reason for quantitative easing is the existential threat to the US and global financial system from interest-rate risk, credit derivatives risk, and interest-rate derivatives risk.

Those risks constitute three deeply-intertwined disaster scenarios which are still out there – indeed they're worse than they ever were before. And if the Federal Reserve were to ever completely lose control of interest rates – these risks could still take down the global financial system in a matter of days through a combination of counterparty risk, financial contagion and liquidity risk.

The first level of interest-rate risk is that of deeply indebted sovereign governments who already can't pay their bills. As an example, the United States is currently about $18 trillion in debt – an amount approximately equal to its total economy in size. With each year that goes by, as the debt continues to mount, the interest payments on that larger debt also increase. This is an issue even with the extremely low interest rates that have been the quite deliberate product of quantitative easing. And this situation could quite quickly turn into a disaster scenario if substantively higher interest rates were to occur.

According to the US Treasury Department, the average interest rate on all US government debt outstanding was 2.408% as of November, 2013 (not including Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities).

Once interest rates have had the time to reset among the various maturities of debt outstanding, a 5% increase in borrowing costs for the federal government with current levels of debt outstanding would triple interest costs. This would raise the federal deficit by $900 billion per year.

Which means that absent a huge tax increase, the money to pay for that additional $900 billion in interest costs would need to be borrowed. There would then be a quick and potentially fatal acceleration in the amount of debt that would have to be issued, with interest climbing on that new debt even as it had to be paid on the existing $18 trillion, bringing the whole disaster forward in time at an even faster rate.

And if we take into account the risk involved with an effectively bankrupt nation that can't pay for imports, and we add not 5% but 10% to the cost of the federal debt – which is still well below the peak seen in the early 1980s when there were lesser economic issues – then we would see a five times increase in annual interest payments, with the annual total deficit soaring to well over $2 trillion dollars per year. With this fantastic increase in interest expenses being financed by still higher deficits, which in turn accelerates the increases in debt outstanding, which then further ratchets up interest expenses, which must be paid for by still more borrowing – clearly this rapidly creates an impossible situation.

Interest-Rate Derivatives Danger

Unmanageable sovereign debt – and compounding interest costs on that debt – is a huge problem for the world, but it's not the largest problem.

The greatest danger is the approximately $561 trillion of interest-rate derivatives that were outstanding as of November of 2013, according to the Bank For International Settlements.

Wall Street and the major financial firms around the world have created fantastic paper profits – and paid out enormous personal bonuses – on the promise that they can do something which they in fact can't do, nor have they ever had the ability to do.

The thinly-capitalized financial firms have promised the major borrowers of the world – which include state, provincial and municipal governments, as well as corporate borrowers, as well as commercial real estate owners – that through the purchase of interest-rate derivatives products, these borrowers will be protected from loss in the event that interest rates shoot up.

Now of course when push came down to shove in practice, Wall Street was completely incapable of covering even the relatively minute damages from the collapse of the $1.2 trillion subprime mortgage derivatives market.

In the graph below, we take a look at the size of the subprime mortgage derivatives market at the time of its collapse, and we compare it to the current interest rate derivatives market. It is a tall chart, because the interest rate derivatives market is more than 450 times the size of the subprime mortgage derivatives market in 2008, and for the subprime derivatives market to even be visible for the eye to see and compare – requires a very tall chart indeed.

Speaking as a former investment banker who in the 1980s helped to create some of the most complex derivatives that had existed up until that time, and who later had a McGraw-Hill book published on the subject titled, "Collateralized Mortgage Obligations, Unlock The Secrets Of Mortgage Derivatives", (1996), the issue is that Wall Street has been ignoring two extraordinary risks that are associated with derivatives. And despite these risks having been proven in practice, they continue to be widely ignored today by Wall Street, by governmental regulators, and by the rating agencies.

Two Fatal Risks: Correlation & Discontinuous Markets

The first major issue is one of correlation. We can view derivatives as being a form of an insurance contract in many cases, where the idea is that an insurance company might sell fire insurance policies in different neighborhoods in California, New York, and Florida, and they get a statistically predictable level of fires occurring in an uncorrelated manner. Because only a few fires occur each year compared to the number of policies that have been written, they can therefore cover their risks and consistently earn money.

The problem with subprime mortgage derivatives was that when the market turned to disaster – the whole subprime market went down together. It was not uncorrelated risk, but rather it turned out to be highly correlated. And the reserves which had been set up to cover uncorrelated risks were nowhere near large enough to meet the promises that had been entered into by the Wall Street firms.

And when we look at interest-rate derivatives – we're looking at an even more correlated degree of risk.

When interest rates rise, they rise across the board for an entire nation, and they may indeed help trigger interest-rate increases in other nations as well.

So there is close to 100% correlation – the simultaneous losses being incurred could be likened to one firestorm spreading over the entire country.

And the reserves that were established to cover statistical assumptions of uncorrelated losses quickly disappear when it is correlated losses on a national basis that happen instead.

Wall Street and the banking industry remain as highly over-leveraged as ever. Just where are these hidden reserves of tens of trillions of dollars worth of capital to honor all of the derivatives contracts?

If every level of state and local government, as well as mass numbers of corporations and real estate owners, were all to simultaneously go to the financial firms which provided them with interest-rate derivatives and demand reimbursement for a potential major increase in interest rates that would create trillions of dollars in annual claims for the interest-rate derivatives outstanding – where, precisely, is the fantastic source of funds for the system as a whole to make good on these derivatives contracts for potentially year after year?

Now most of the dollar volume of derivatives outstanding are not actually independent risks, but instead represent the same risk being resold time and again in different forms, which in theory reduces the risks for each firm on a micro basis. However, we also know that in practice this creates an elaborate chain of promises (a.k.a. systemic "counterparty risk") that links together the solvency of all of the financial firms. And it's the estimation of the profitability of each one of these levels of interconnected promises which has allowed for the payment of so much bonus income.

But what it all comes down to is credibility. Does Wall Street and the other providers of interest-rate derivatives actually have the capital tucked away somewhere to cover the many trillions of dollars in increased interest payments for the entire nation, year after year, if rates were to rise by 5% or 10% or even more?

There's no possible way. It would be an annihilation scenario, short of even greater levels of government interventions.

The other crucial and interrelated risk is one we have seen occur in practice, which is that of discontinuous markets, also sometimes known as market gapping. And this has been well understood for years now, because we not only saw it in 2008, but we also saw it in 1998 with Long-Term Capital Management.

That is, the risk models which the Wall Street firms use – and which the rating agencies and regulators rely upon – assume that there will be smooth and continuous markets where a buyer can always be found. So if a firm is reaching the point where the losses are too much for it to handle, it can effectively exit a strategy before the losses on that strategy become an existential threat to the solvency of the firm.

As a round number example, if the price starts at 100, and the losses at 80 would threaten the solvency of the firm, then the firm might intend to exit the strategy at 92, thereby taking a painful loss but one which avoids bankruptcy. With the core assumption being that the firm can exit its position at will, so long as it is willing to accept the losses – whether that be at a price of 93, 92 or 91.85, because the markets are continuous.

These assumptions are essential when it comes to making those spreadsheets work, and in calculating how safe a strategy is, how much money is actually being made, and what level of bonuses can be paid out. And these assumptions do indeed usually work, as markets as a whole are reasonably continuous ~99.9% of the time.

The problem is what happens during the other ~0.1% of the time, with years or even decades passing between major events. One popular term for those quite uncommon events is a "black swan". However, discontinuous markets aren't really a true black swan, as we know for a fact that like earthquakes – a big one inevitably happens every now and then. A better term is a "fat tail" event, where every now and then the usual statistical modeling assumptions get tossed right out the window.

Whatever the name, all of the major players in the market get hit at the same time. It was subprime mortgage derivatives in 2008, it could be interest rate derivatives the next time, or it could start with credit derivatives.

Everybody wants out – simultaneously. Nobody wants to buy in. Buyers disappear, just like they did in 2008, and just like they did in 1998. The market drops straight from 96 to 65 without ever trading at 94 or 92 or 85 – and there might not even be any buyers at 65. Or at 45. Or at 25.

Because of the gap, there is no dynamic exit strategy, there is no way to exit the claims before they destroy the solvency of the firm. No firms are able to exit before 80 – meaning all the big players simultaneously become insolvent. Within a vast interlocking web of counterparty risk, to the extent that the actual failure of even one "Too-Big-To-Fail" bank or Systemically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) could pull down the global financial world – and the deeply indebted sovereign governments along with them.

The governments of the world have been building derivatives "clearinghouses" into the system which are intended to knock out the counterparty risk - but the ultimate guarantor of the clearinghouses are the deeply indebted sovereign governments. This mutual exposure of the major financial firms and sovereign governments to each other creates a potentially fatal toxic feedback loop.

That is, in order to preserve the financial system, the sovereign governments who are already heavily indebted may potentially need to bail out the banks and/or clearinghouses when it comes to the interest-rate derivatives contracts.

This would take sovereign nations that are already facing rapidly accelerating interest-rate costs and ever more impossible deficits, and radically increase the amount of debt that they owe, thereby increasing the chances of their insolvency.

Simultaneously, through credit derivatives, the financial institutions are heavily exposed to bankruptcy risk on the part of the nations.

So an inability to pay interest-rate derivatives leads to potential insolvency of the banks, the bailing out of which bankrupts the nations, which through credit derivatives creates another round of bankrupting the banks unless they are bailed out, and so forth.

So the world is currently as exposed as it was in 2008 to this triple combination of counterparty risk, with the associated contagion risk, which can then set off a fatal episode of liquidity risk (i.e. another institutional bank run), that could melt the system down in a matter of days – or even hours.

This is all closely tied in with the rapid spread of "bail-in" rules and procedures around the world, for the International Monetary Fund as well as the national governments are keenly aware of the dangers within this complex chain of interrelationships.

The IMF and the various nations are acutely aware that derivatives exposures can help set off another chain of counterparty risk, contagion risk, and liquidity risk that could rapidly bring down both the banking system and national governments.

This is precisely why, as covered in my article, "Did An Obscure IMF Document Start A Global Bail-In Revolution?", so many nations are rapidly moving to have the ability to directly seize assets from unsuspecting lenders, investors and depositors, in order to deal with these risks which are in fact greater now than ever before.

Understanding The Real Core Of Quantitative Easing

So, given this extraordinarily irresponsible ongoing behavior by the global financial system, how do the nations of the world keep a lid on it? How to keep interest-rate derivatives from destroying the world?

Well, they do so by controlling interest rates.

The entire point behind Quantitative Easing Two, as well as each of the Twists, was the Fed doing something it had not traditionally done, which was to take direct control of medium-term interest rates, long-term interest rates, and mortgage interest rates.

As I wrote to my subscribers within a couple of days of QE2 being announced, people were missing the most important part of the announcement. That is, this wasn't so much the Federal Reserve directly funding the treasury, even though many people have misinterpreted this as being the case.

The bigger issue is that the Federal Reserve did not buy the bonds from the Treasury, but rather they bought the bonds in the secondary market. And because they quickly became the largest player, and because they had the credibility of not having only theoretically unlimited money creation capability but proving it in practice, they were able to take control of interest rates across the United States.

So what was Quantitative Easing Three?

It was the unlimited creation of new money to purchase treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities in the secondary market, thereby keeping effective control of interest rates.

Now this doesn't mean that a 1-2% or even a somewhat larger increase in interest rates is necessarily going to pose an existential threat.

The system can withstand a moderate increase in interest rates, the Federal Reserve knows that, and that is why it tapered QE3 down until the growth stopped (with halting the growth of QE being a very different thing than actually unwinding QE, and selling the assets).

But make no mistake about it, the US government and the Federal Reserve are fully aware that we have a potentially existential event here.

If the US government were to lose control of interest rates, and interest rates shoot up, then it risks a massive sovereign credit crisis, it risks a credit derivatives crisis, and it risks the financial Armageddon of an interest-rate derivatives crisis.

That is why quantitative easing was created in the first place. And a return to QE remains the primary defense against a disaster which could otherwise consume the global financial order in a matter of days.

There's also the closely related issue of the credit derivatives that are still outstanding around the world.

And in many cases here, whether we're looking at sovereign credit derivatives, which is insurance on nations' abilities to pay their debts, or whether we're looking at corporate credit derivatives – a sovereign credit-imperiling rise in interest rates, accompanied by massive increases in the cost of borrowings for all the corporations that have so highly leveraged themselves in the expectation that we'll have an unending environment of low interest rates, could quickly become catastrophic.

All three are tightly interlocked: sovereign credits, interest-rate derivatives, and credit derivatives.

And if we had a true return to market interest rates, all three could quickly combine to take down the global financial order as we know it, and the value of most people's investments along with it.

And how is this prevented?

It is by, if needed, creating of money out of thin air on a massive basis.

It's not so much about running the printing presses, but rather to try to deal with something that is even more volatile and dangerous, which is a potential collapse of the global financial order through a combination of counterparty risk, contagion risk, and liquidity risk that is created and fanned by the three danger zone areas of sovereign credits, interest-rate derivatives and credit derivatives.

Accepting That The World Has Changed

Neither of the two dominant belief systems in the markets fully accepts this connection between quantitative easing and preventing a potential financial implosion that could still take down the world in a matter of days and weeks.

If we look at the mainstream, there is this pervasive idea that we are returning to normal in some way, even if we're not quite there yet. We just have to sit this out for a little bit longer and trust that things will get right back to where they used to be.

On the other hand, there are many in the contrarian school who have been continuously expecting economic and financial collapse for a number of years now. They look at the fantastic scale of monetary creation associated with quantitative easing, and are convinced that the end must inevitably be nigh.

Let me suggest that neither school of thought is fully accepting the new reality that we currently live in.

The end of the financial system that characterized the second half of the 20th Century isn't nigh – it already happened. What needs to be understood is that our old investment and monetary system is gone. It ended in September and October of 2008, when extraordinary measures were taken to save the financial system – and which are still being taken today, as they remain needed.

We have a highly dysfunctional system in which the so-called Too-Big-To-Fail financial institutions, or SIFIs, continue to take on risk without end, even as sovereign governments approach effectively bankrupt debt levels, even as much worse dangers come at us with effectively bankrupt government-guaranteed retirement systems.

Given that the toxins remain and the risks are not yet being controlled – we could expect that a return to traditional free market forces would almost certainly collapse the financial order sometime over the next few years or decades – absent government interventions.

Free market forces have created more real wealth for the world than any other economic system – but we have to remember that these forces do so by requiring honesty. Individuals acting in their own self-interest make the informed decisions about prices and returns, that in turn determine the best allocation of resources for economic growth. Honesty would necessarily force the collapse of a dysfunctional and unstable system in which resources are redistributed primarily by political and monetary decisions in a manner that is not understood by the general public or average voter.

Preventing the natural results of honesty and free markets is exactly why the government interventions occurred.

Therefore, should market conditions ever return in such a way as to threaten this fragile and unnatural financial order that has only come to pass in recent years, then we can expect a swift return to massive government interventions. Of which both the extraordinary level of quantitative easing that's occurring around the world right now, as well as this rapidly spreading idea of bail-ins (as explained here), are each massive government interventions that exist to stabilize a deeply unhealthy and unstable global order.

Therefore, all investors should be taking this reality into account with all investment decisions – even if diminishingly few are. And the best starting point is to look at the situation, and accept the reality that government-dominated markets are here, and they are likely to stay for as long as the governments can keep them that way.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about just one of the ways in which a rapidly shifting world is removing the foundations beneath conventional investing - even while most investors continue to follow the traditional strategies, unaware of just how much the financial playing field has changed.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about just one of the ways in which a rapidly shifting world is removing the foundations beneath conventional investing - even while most investors continue to follow the traditional strategies, unaware of just how much the financial playing field has changed.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

An "eye-opener"

tutorial of yet another kind is linked here, and it shows how much of what the public believes to be true about stock market history - is merely an illusion, which also just happens to facilitate the redistribution of wealth.

An "eye-opener"

tutorial of yet another kind is linked here, and it shows how much of what the public believes to be true about stock market history - is merely an illusion, which also just happens to facilitate the redistribution of wealth.

If you find these "eye-openers" to be interesting and useful, there is an entire free book of them available here, including many that are only in the book. The advantage to the book is that the tutorials can build on each other, so that in combination we can find ways of defending ourselves, and even learn how to position ourselves to benefit from the hidden redistributions of wealth.