Rising Interest Rates Could Inflict 400X The Losses Of Subprime Mortgages In 2008 - Will That Keep Rates Low?

by Daniel Amerman, CFA

Why are interest rates at historic lows in the United States and around the world?

The widely-accepted answer is that very low interest rates exist for the purpose of stimulating economic growth and corporate profits, and are thereby helping the United States and other nations that are struggling with persistent and deep-rooted economic problems.

However, if we accept this answer, then another question arises. If the US economy is booming while unemployment purportedly nears a mere 5% – then why do interest rates remain so low? Why was there continuous drama about whether the Federal Reserve would very slightly increase interest rates in 2015, or whether it will make other quite small adjustments in 2016?

A truly healthy economy and stock market should by definition be able to easily handle a minor increase in interest rates, keeping in mind that what is proposed is still only a small fraction of what market rates previously were for decades on end.

So why the fear by both the Fed and the markets?

To understand, we need to explore why these very low interest rates were created in the first place and have remained in place for all these years: they are a defensive attempt to prevent what could otherwise very quickly become two different potential disaster scenarios for global financial markets.

Now just to be very clear – this is not a "gloom & doom" analysis, there is no inevitable destruction of the financial world, and there are many possible economic and political futures. Instead, there are two issues here : #1, that of risk itself; and #2, the attempted containment of risk.

When it comes to issue #1, the two threats are deadly and entirely real, there is enormous latent or stored energy in each threat, and each could indeed bring down the global financial system as we know it, along with the value of our individual savings and investments. Now, whether a "triggering event" does in fact occur which releases the stored energy and changes the world and our own financial security and retirements along with it – that is the heart of the real question.

The most likely "triggering event" would be a substantial and sustained future increase in interest rates. Governments and central banks therefore have powerful incentives to try to prevent such a "triggering event" from occurring.

And it is simply impossible to explain the past or the present of interest rates – let alone make informed judgments about the path ahead – without understanding the constraints imposed by issue #2, the attempted containment of these dual risks.

(It is worth noting that the highly publicized 0.25% increase in the Fed Funds rate range by the Federal Reserve in December of 2015 was in contrast very minor, it was much delayed, and whether it will be sustained is a matter of market skepticism. In other words it was highly unusual when compared to previous interest rate increases, which is consistent with the attempted containment of the dual risks.)

Very Low Interest Rates: Trying To Control Two Global Risks

The main reason for persistent very low interest rates is the threat to the US and global financial system from direct interest-rate risk as well as derivatives interest-rate risk.

Those risks constitute two distinct but deeply-intertwined potential disaster scenarios which are not only still out there – but each are significantly more dangerous than they were before 2008. And if the Federal Reserve were to ever completely lose control of interest rates – these risks could still take down the global financial system with surprising speed through a combination of financial contagion, liquidity risk, and counterparty risk.

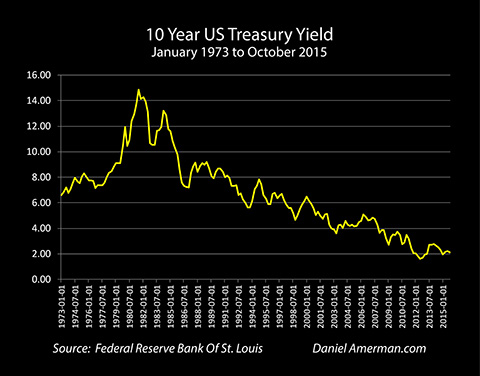

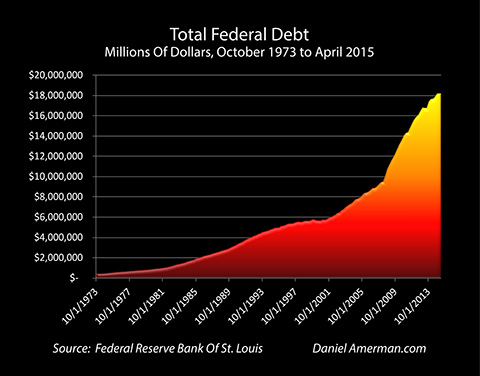

The first level of interest-rate risk is that of deeply indebted sovereign governments. As an example, the United States is currently over $18 trillion in debt – an amount approximately equal to its total economy in size. This is more than double the total federal debt of $8.9 trillion that was outstanding in 2007, before the financial crisis of 2008.

As explored here, once interest rates have had the time to reset among the various maturities of debt outstanding, a 5% increase in borrowing costs for the federal government with current levels of debt outstanding would triple interest costs. This would raise the federal deficit by $900 billion per year.

With each year that goes by, as the debt continues to mount, the interest payments on that larger debt also increase. This is an issue even with the current extremely low level of interest rates. And this situation could quite quickly turn into a disaster scenario if substantively higher interest rates - i.e., normal free market rates - were to return.

Which is exactly why interest rates are currently so low. According to the US Treasury Department, the average interest rate on all US government debt outstanding is somewhat less than 2.5% (not including Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities).

It should also be noted that a similar level of interest rate risk is faced by the deeply indebted major cities of the United States, as well as the heavily indebted states. So a substantial increase in interest rates would not only send federal deficits soaring – but also state and local deficits as well, which would then likely lead to major increases in state & local tax rates. Major corporations which can directly access the capital markets via bond borrowings have also taken advantage of pervasive low interest rates to load up on low cost debt as well.

What the federal government, state and local governments and major corporations of the United States have in common then, is a very powerful motivation to keep interest rates relatively low for the indefinite future – albeit at the expense of savers & investors.

Interest-Rate Derivatives Danger

Unmanageable sovereign debt – and compounding interest costs on that debt – is a huge problem for the world, but it's not the largest problem.

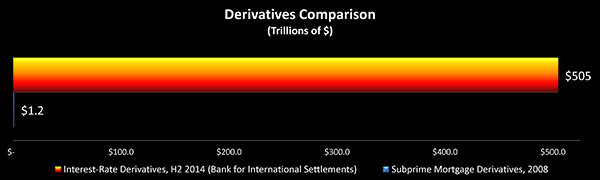

The greatest danger is the about $500 trillion of interest-rate derivatives that are currently outstanding, according to the Bank For International Settlements.

Wall Street and the major financial firms around the world have created fantastic paper profits – and paid out enormous personal bonuses – on the promise that they can do something which they in fact can't do, nor have they ever had the ability to do.

The thinly-capitalized financial firms have promised the major borrowers of the world – which include state, provincial and municipal governments, as well as corporate borrowers, as well as commercial real estate owners – that through the purchase of interest-rate derivatives products, these borrowers will be protected from loss in the event that interest rates shoot up.

Now of course when push came down to shove in practice, Wall Street was completely incapable of covering even the relatively minute damages from the collapse of the $1.2 trillion subprime mortgage derivatives market.

In the graph below, we take a visual look at the size of the subprime mortgage derivatives market at the time of its collapse, and we compare it to the current interest rate derivatives market. You may need to squint and lean towards the screen to see the blue line for the subprime mortgage derivatives market, as it is only full 1 pixel wide, but it is indeed there, even if it is hard to see in comparison to an interest rate derivatives market that is more than 400 times its size.

Speaking as a former investment banker who in the 1980s helped to create some of the most complex derivatives that had existed up until that time, and who later had a McGraw-Hill book published on the subject titled, "Collateralized Mortgage Obligations, Unlock The Secrets Of Mortgage Derivatives", (1996), the issue is that Wall Street has been ignoring two extraordinary risks that are associated with derivatives. And despite these risks having been proven in practice, they continue to be widely ignored today by Wall Street, by governmental regulators, and by the rating agencies.

Correlation Risk

Derivatives carry two distinct but intertwined dangers, and the first is correlation. We can view derivatives as being a form of an insurance contract in many cases, where protection against possible losses is being sold in exchange for premium income.

As an example, an insurance company might sell fire insurance policies in different neighborhoods in California, New York, and Florida. They would expect to get a statistically predictable level of fires to occur in an uncorrelated manner, i.e., whether a fire occurs in New York has nothing whatsoever to do with whether a fire happens in California. Because relatively few fires occur each year compared to the number of policies that have been written, they can therefore cover their risks and consistently earn profits as well.

The problem with subprime mortgage derivatives in 2008 was that when the market turned to disaster – the whole subprime market went down together. Among the many other issues with subprime mortgages was the assumption that perhaps a pocket would go bad in California, or perhaps Florida, but the mortgages would be fine in the rest of the nation, and the income from performing subprime loans in the rest of the nation would cover the losses. Much like what would happen with fire insurance, or auto insurance.

The difference was that the same national firms were making the same bad lending decisions in every part of the nation simultaneously. So the risks turned out to be highly correlated – they hit everywhere at the same time. And the reserves which had been set up to cover uncorrelated risks evaporated almost instantly, because they were grossly inadequate when it came to meeting the promises that had been entered into by the Wall Street firms all across the nation.

And when we look at interest-rate derivatives – we're looking at an even more correlated degree of risk.

When interest rates rise, they rise across the board for an entire nation, and they may indeed help trigger interest-rate increases in other nations as well. Issuers have entered into trillions of dollars of contracts with Wall Street and other financial firms to cover their risk if interest rates increase. And if interest rates do increase substantially – they increase for the nation as a whole, in every state, for every borrower, and for every category.

So there is close to 100% correlation – the simultaneous losses being incurred could be likened to one firestorm spreading over the entire country.

And the reserves that were established to cover statistical assumptions of uncorrelated losses quickly disappear when it is correlated losses on a national basis that happen instead.

Where Is The Money?

Recent regulatory changes notwithstanding, Wall Street and the banking industry remain highly leveraged because that is the very nature of the industry. So just where are these hidden reserves of many trillions of dollars worth of capital to honor all of the derivatives contracts?

As an example, let's say a city had issued $100 million in variable rate debt, and they wanted to borrow at the very low short term interest rate of 2%, but they also wanted to have protection against having to pay more if interest rates rose. For this protection, they would likely be highly encouraged to enter into a derivatives contract, where essentially the city would pay a financial company to cover the risk if rates went up.

So if short-term interest rates rose from 2% to 7%, the city would have to pay $7 million a year in interest payments on their $100 million debt (instead of $2 million), but they could then turn to financial company who would pay the city the $5 million per year difference, leaving the city's borrowing costs unchanged.

Now the issue is that if interest rates were to rise by 5% across the entire nation, and every level of state and local government, as well as mass numbers of corporations and commercial real estate owners were to all owe their investors 5% higher interest rates, and they all simultaneously went to the financial firms which provided them with interest-rate derivatives and essentially said "I want the 5% you contractually promised to pay me if interest rates went up by 5%" – where, precisely, is the fantastic source of funds for the system as a whole to make good on these derivatives contracts for potentially year after year?

Importantly, most of the dollar volume of derivatives outstanding are not actually independent risks, but instead represent the same risk being resold time and again in different forms, which in theory reduces the risks for each firm on a micro basis. However, we also know that in practice this creates an elaborate chain of promises (a.k.a. systemic "counterparty risk") that links together the solvency of all of the financial firms. And it's the estimation of the profitability of each one of these levels of interconnected promises which has allowed for the payment of so much bonus income.

And make no mistake - it is the bonus income and other personal incentives for executives that has led Wall Street and the rest of global financial system to take on hundreds of trillions of dollars worth of interest-rate derivatives risk.

But what it all comes down to is credibility. Do Wall Street and the other providers of interest-rate derivatives actually have the capital tucked away somewhere to cover the many trillions of dollars in increased interest payments for the entire nation (and the entire world), year after year, if rates were to rise by 5% or 10% or even more?

In practice, we know that Wall Street wasn't good for their promises on a little more than $1 trillion in subprime mortgage derivatives. There are more than 400 times as many interest-rate derivatives currently outstanding as there were subprime mortgage derivatives in 2008. There's no possible way. It would be an annihilation scenario, short of even greater levels of government interventions.

The basic relationship is that the banks and financial companies sell insurance contracts they couldn't possibly honor if there is a substantial and sustained increase in interest rates, in exchange for what are essentially lucrative insurance premiums. Honoring the insurance if rates rose to the market levels of past decades would bankrupt the system. So the governments keep rates low so that the system isn't destroyed, and the banks keep the profits from the "insurance" that they won't have to pay out on.

Natural Risks vs Political Risks

Another way of looking at this is to say that traditional insurance companies generally sell protection against "natural" risks they do not control but are considered to be statistically predictable, within a fairly tightly regulated industry.

In contrast, interest-rate derivatives are a relatively lightly regulated industry where the product being sold – protection against interest rate changes – is often under the more or less direct control of the central banks and governments. So long as enough insurance is sold, i.e. about $500 trillion in notional interest-rate derivatives outstanding, then the governments have an existential interest in making sure that the "insurance" claims against the financial firms never reach the level that would imperil the stability of the system.

One could even say that by having created such a fantastically large level of risk the financial firms are effectively blackmailing the governments to make sure they never have to pay out, and the governments are allowing this because 1) so much money is being made by connected insiders; 2) it hasn't actually blown up yet; and 3) the voters have no clue about what is actually happening.

There is an elaborate vocabulary and mathematics for derivatives that goes well beyond the knowledge of most financial professionals, let alone the general public. They are created by the largest and most prestigious financial firms in the world. Yet, once the veneer of these layers of impenetrable mathematics, jargon, "expertise" and the perception of overwhelming financial authority is pierced – what is left is nothing more than a basic form of insurance scam, i.e. collecting premiums for policies that can't be honored. And if something does goes wrong with that scam – then it is all of us who are the ones who will pay together, as taxpayers and investors.

When we understand this, then we can understand what may be the biggest reason of all for why for the indefinite future, interest rates won't be allowed to go to substantially higher levels on a sustained basis. Or at least this won't happen for so long as central banks and governments retain sufficient control to keep interest rates in a relatively low range, when compared to historical levels.

Market Discontinuities aka Market Gapping

The other crucial and interrelated risk is one we have seen occur in practice, which is that of discontinuous markets, also sometimes known as market gapping. And this has been well understood for years now, because we not only saw it in 2008, but we also saw it in 1998 with Long-Term Capital Management. We also saw this risk occurring in practice with ETF prices as recently as the stock market rout of August, 2015, as explored here.

That is, the risk models which the Wall Street firms use – and which the rating agencies and regulators rely upon – assume that there will be smooth and continuous markets where a buyer can always be found. So if a firm is reaching the point where the losses are too much for it to handle, it can effectively exit a strategy before the losses on that strategy become an existential threat to the solvency of the firm.

As a round number example, if the price starts at 100, and the losses at 80 would threaten the solvency of the firm, then the firm might intend to exit the strategy at 92, thereby taking a painful loss but one which avoids bankruptcy. With the core assumption being that the firm can exit its position at will, so long as it is willing to accept the losses – whether that be at a price of 93, 92 or 91.85, because the markets are continuous.

These assumptions are essential when it comes to making those spreadsheets work, and in calculating how safe a strategy is, how much money is actually being made, and what level of bonuses can be paid out. And these assumptions do indeed usually work, as markets as a whole are reasonably continuous ~99.9% of the time.

The problem is what happens during the other ~0.1% of the time, with years or even decades passing between major events. One popular term for those quite uncommon events is a "black swan". However, discontinuous markets aren't really a true black swan, as we know for a fact that like earthquakes – a big one inevitably happens every now and then. A better term is a "fat tail" event, where every now and then the usual statistical modeling assumptions get tossed right out the window.

Whatever the name, all of the major players in the market get hit at the same time. It was subprime mortgage derivatives in 2008, it could be interest rate derivatives the next time, or it could start with credit derivatives.

Everybody wants out – simultaneously. Nobody wants to buy in. Buyers disappear, just like they did in 2008, and just like they did in 1998. The market drops straight from 96 to 65 without ever trading at 94 or 92 or 85 – and there might not even be any buyers at 65. Or at 45. Or at 25.

Because of the gap, there is no dynamic exit strategy, there is no way to exit the claims before they destroy the solvency of the firm. No firms are able to exit before 80 – meaning all the big players simultaneously become insolvent. Within a vast interlocking web of counterparty risk, to the extent that the actual failure of even one "Too-Big-To-Fail" bank or Systemically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) could pull down the global financial world – and the deeply indebted sovereign governments along with them.

Toxic Feedback Loops

The governments of the world have been building derivatives "clearinghouses" into the system which are intended to knock out the counterparty risk - but the ultimate guarantor of the clearinghouses are the deeply indebted sovereign governments. This mutual exposure of the major financial firms and sovereign governments to each other creates a potentially fatal toxic feedback loop.

That is, in order to preserve the financial system, the sovereign governments who are already heavily indebted may potentially need to bail out the banks and/or clearinghouses when it comes to the interest-rate derivatives contracts.

This would take sovereign nations that are already facing rapidly accelerating interest-rate costs and ever more impossible deficits, and radically increase the amount of debt that they owe, thereby increasing the chances of their insolvency.

Simultaneously, through credit derivatives, the financial institutions are heavily exposed to bankruptcy risk on the part of the nations.

So an inability to pay interest-rate derivatives claims leads to the potential insolvency of the banks, the bailing out of which bankrupts the nations, which through credit derivatives creates another round of bankrupting the banks unless they are bailed out, and so forth.

So the world is currently as exposed as it was in 2008 to this triple combination of counterparty risk, with the associated contagion risk, which can then set off a fatal episode of liquidity risk (i.e. another institutional bank run), that could melt the system down in a matter of weeks.

This is all closely tied in with the rapid spread of "bail-in" rules and procedures around the world, for the International Monetary Fund as well as the national governments are keenly aware of the dangers within this complex chain of interrelationships.

The IMF and the various nations are acutely aware that derivatives exposures can help set off another chain of counterparty risk, contagion risk, and liquidity risk that could rapidly bring down both the banking system and national governments.

This is precisely why, as covered in my article, "Did An Obscure IMF Document Start A Global Bail-In Revolution?", so many nations are rapidly moving to have the ability to directly seize assets from unsuspecting lenders, investors and depositors, in order to deal with these risks which are in fact greater now than ever before.

Controlling The Risk

So, given this extraordinarily irresponsible ongoing behavior by the global financial system, how do the nations of the world keep a lid on it? How to keep interest-rate derivatives from destroying the world?

Well, they do so by controlling interest rates.

That is the point of current Federal Reserve policy, as well as the policies of the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan among others.

Now this doesn't mean that a 1-2% or even a somewhat larger increase in interest rates is necessarily going to pose an existential threat.

The system can withstand a moderate increase in interest rates, the Federal Reserve knows that, and that is why it tapered QE3 all the way down until the growth stopped (with halting the growth of QE being a very different thing than actually unwinding QE, and selling the assets). And it is also why there are frequent discussions of a small increase in interest rates, which could very well happen in the near future.

But make no mistake about it, the US government and the Federal Reserve are fully aware that we have a potentially existential event here.

If the US government were to lose control of interest rates, and interest rates shoot up, then it risks a massive sovereign credit crisis, it risks a credit derivatives crisis, and it risks the financial Armageddon of an interest-rate derivatives crisis.

That is why quantitative easing was created in the first place. And a return to QE along with a quick return to near zero interest rates remain the primary defenses against such a disaster.

There's also the closely related issue of the credit derivatives that are still outstanding around the world.

And in many cases here, whether we're looking at sovereign credit derivatives, which is insurance on nations' abilities to pay their debts, or whether we're looking at corporate credit derivatives – a sovereign credit-imperiling rise in interest rates, accompanied by massive increases in the cost of borrowings for all the corporations that have so highly leveraged themselves in the expectation that we'll have an unending environment of low interest rates, could quickly become catastrophic.

All three are tightly interlocked: sovereign credits, interest-rate derivatives, and credit derivatives.

And if we had a true return to market interest rates, all three could quickly combine to take down the global financial order as we know it, and the value of most people's investments along with it.

And how is this prevented?

It is by, if needed, creating of money out of thin air on a massive basis.

It's not so much about running the printing presses, but rather to try to deal with something that is even more volatile and dangerous, which is a potential collapse of the global financial order through a combination of counterparty risk, contagion risk, and liquidity risk that is created and fanned by the three danger zone areas of sovereign credits, interest-rate derivatives and credit derivatives.

Accepting That The World Has Changed

Neither of the two dominant belief systems in the markets fully accepts our new financial world, and the nontraditional ways in which governmental interventions in the form of very low interest rates and monetary creation are being used to stabilize the current system and prevent a new financial crisis.

If we look at the mainstream, there is this pervasive idea that we are returning to normal in some way, even if we're not quite there yet. We just have to sit this out for a little bit longer and trust that things will get right back to where they used to be.

Those who don't accept this mainstream perspective are often moved all the way over to the Gloom & Doom camp of those who have been continuously expecting economic and financial collapse for a number of years now. They look at the fantastic scale of monetary creation associated with quantitative easing, and are convinced that the end must inevitably be nigh.

Let me suggest that the two schools of thought in combination create a False Dichotomy (as explored here) where neither school of thought is fully accepting the new reality that we currently live in, meaning both the mainstream AND the Gloom & Doomers could be dangerously wrong.

The end of the financial system that characterized the second half of the 20th Century isn't nigh – it already happened. What needs to be understood is that our old investment and monetary system is gone. It ended in September and October of 2008, when extraordinary measures were taken to save the financial system – and which are still being taken today, as they remain needed.

Given that the toxins remain and the risks are not yet being controlled – there is a strong chance that removing all governmental interventions and returning to traditional free market forces would collapse the financial order in the near term. (Now, whether that is necessarily a bad thing, or merely the painful medicine needed to be temporarily endured to allow a return to genuine economic health over the medium to long term is another issue.)

Free market forces have created more real wealth for the world than any other economic system – but we have to remember that these forces do so by requiring honesty. Individuals acting in their own self-interest make the informed decisions about prices and returns, that in turn determine the best allocation of resources for economic growth. Honesty would necessarily force the collapse of a dysfunctional and unstable system in which resources are redistributed primarily by political and monetary decisions in a manner that is not understood by the general public or average voter.

Preventing the natural results of honesty and free markets is exactly why the government interventions occurred.

So, should genuine market forces ever return in such a way as to threaten this unnatural financial order that has only come to pass in recent years, then we can expect a swift return to massive government interventions.

This type of reasoning is reasonably well accepted among institutional investors, even if it is not usually phrased in quite this manner, and it explains this otherwise bizarre phenomena in recent years of bad economic news producing increases in market prices.

The relationship is that market prices are propped up by governmental interventions, these prices are endangered by the withdrawal of such interventions, this possibility makes institutional investors very nervous, and so each time there is bad news, the chances of the government reducing the level of interventions recedes, and relieved investors then bid up asset prices.

Let me suggest that interest rates simply can't be understood without understanding that seemingly counterintuitive relationship.

It is the potentially catastrophic consequences if interest rates were to rise on a substantial and sustained basis that forms the primary defense against rising interest rates.

Which works unless and until something unexpected happens, or a mistake is made, or both, and control is lost. And if that were to happen...

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

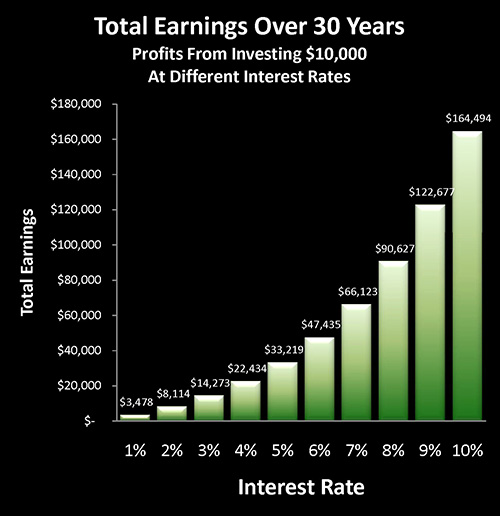

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

National debts have been reduced many times in many nations ─ and each time the lives of the citizens have changed. The "eye-opener" linked here reviews four traditional methods that can each change your daily life, and explores how governments use your personal savings to pay down their debts in a manner which is invisible to almost all voters.

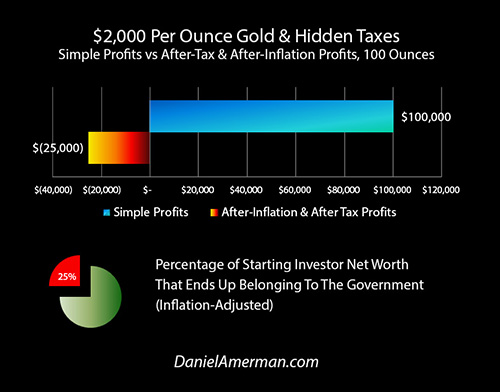

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows a quite different redistribution of wealth, which is how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unsuspecting precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

If you find these "eye-openers" to be interesting and useful, there is an entire free book of them available here, including many that are only in the book. The advantage to the book is that the tutorials can build on each other, so that in combination we can find ways of defending ourselves, and even learn how to position ourselves to benefit from the hidden redistributions of wealth.