How Do Low Rates & Inflation Work Together To Challenge The Foundations Of Retirement Investing?

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

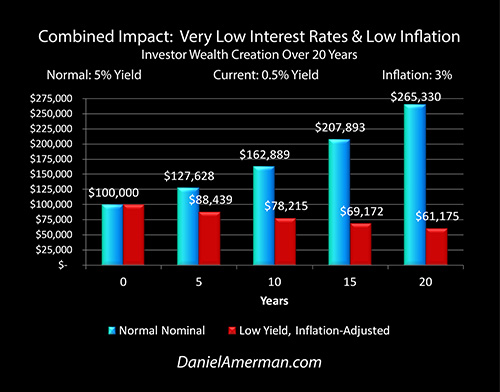

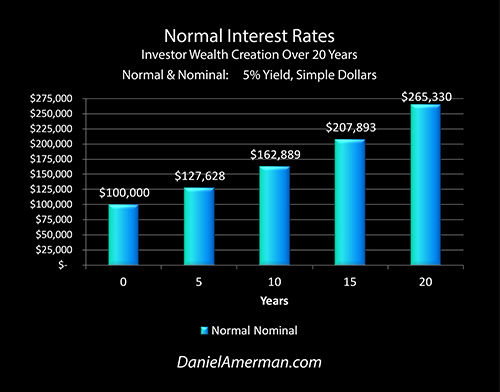

TweetThe blue bars in the graph below show how the average person can ordinarily build wealth through saving and letting their money work for them. With the passage of time, there is a steady increase in both their wealth and their financial security. The blue bars represent normal market conditions, and typical interest rates.

The red bars represent the current situation for the US and other nations over the last several years. Which is that on average, savers slowly lose the purchasing power of their savings, and the more time that goes by, the greater the loss and the less the financial security.

What the red bars show is the quite personal impact of something vast and otherwise impersonal – which is governments creating what economists refer to as negative real interest rates. As is being done as a matter of stated policy right now in many places around the world including the United States, with "real" meaning inflation-adjusted. (Europe and Japan also currently have "nominal" negative interest rates - where investors may actually pay money to the borrower - which is different than the subject of this analysis.)

Few people aside from economists and financial professionals are aware of this policy, let alone how it works. Yet, because it dramatically changes investment results for the entire nation, it is already affecting how much wealth you build, and may have a powerful impact on when you personally retire as well as what your own standard of living will be in retirement.

In this resource we will walk through a four part series of financial analyses to close that knowledge gap, so that you will have the information you need to understand the very personal implications for your own life now and in the years to come.

Normal Times

Our starting analysis is a common investment strategy, in normal times, viewed from the usual perspective – which is simple (nominal) dollars, i.e. not adjusted for inflation. We invest at 5% in a bond or certificate of deposit, and if we start with $100,000, then by the end of year one we have $105,000.

As shown in the above graphic, by the end of year five we are up to $127,628, by year ten that is up to $162,889, and we're up over $265,000 in twenty years. Very simple, very normal, this is how wealth creation is supposed to work, and is why the sooner we start saving, the better off we are.

Very Low Interest Rates

Unfortunately, however, that isn't how things have actually been working out in practice. Instead of high or moderate interest rates rapidly building wealth, we've had very low interest rates in the United States and around much of the world for some years now.

These unusually low interest rates are no accident or happenstance, but rather are created as a very deliberate and openly stated matter of governmental policy. Indeed, take a look at the financial pages of a major newspaper on almost any given day, and there is a good chance there will be discussion of some aspect of the Federal Reserve's policy of creating very, very low interest rates, or perhaps about whether rates will be moved up a bit so they are just very low instead. (The highly publicized 0.25% increase in the Fed Funds rate range by the Federal Reserve in December of 2015 still leaves us with very, very low interest rates by historical standards.)

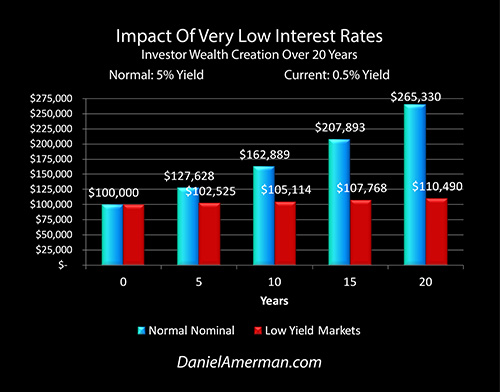

So how do our commonplace plans for wealth creation hold up with the current situation of very low interest rates?

Our second analysis incorporates very low interest rates, and the impact on a saver is shown visually in the graph above. If the earnings rate drops from 5.0% to 0.5%, then the saver doesn't have $105,000 at the end of the year – but rather $100,500.

Instead of having $127,628 in savings at the end of year five, the saver has only $102,525.

And if the unusually low interest rates that we have seen in recent years continue to persist, the saver earns only $10,490 in profits over the next 20 years, instead of the $165,330 they might have received in normal times – and may have been counting on.

A Low Rate Of Inflation

It is also important to keep in mind something that most people don't think about much, which is exactly why it is that for just about every year of our lives the dollar has been worth at least a little bit less on December 31st than it had been when the year started.

To the extent that this slow erosion of the value of what our money will buy for us has been a continuous process throughout our lives, most people might think this is just a natural feature of money, something that nobody really has control over.

The truth however is that inflation is no accident, but instead, just as with low interest rates, it is a matter of deliberate and openly discussed governmental policy.

The prevailing economic theory is that stable economic growth for a nation is best achieved by creating a low to moderate rate of inflation, i.e., steadily reducing the value of money by a little bit every year. Now while it may seem minor most years, the effect is cumulative, and this is why for someone in their mid 70s to 80s, one dollar today will only buy about what five cents would have purchased when they were born in the 1930s.

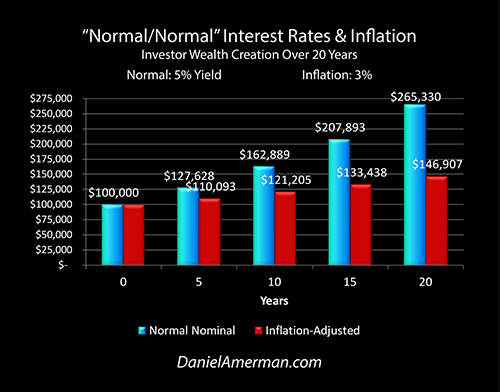

So our third financial analysis is to take into account what a low rate of inflation does to the purchasing power of our savings. And to properly isolate the separate effects of inflation from that of interest rate changes, we'll return to a normal 5% earnings yield, while factoring in a "normal" inflation rate of 3% – which is quite common over the long term.

Because the purchasing power of a dollar falls to 86.3 cents over five years, this means that our $127,628 in simple dollars only has a purchasing power of $110,093.

And because even a low 3% annual rate of inflation results in a dollar only being worth 55.4 cents by the time we are 20 years out, the purchasing power of $265,330 becomes only $146,907.

The above could be called "Normal/Normal" and on average, this type of situation has represented financial reality for much of our lives. "Normal" interest rates are high enough to substantially reward savers over time, and the farther out in time we go, then the more wealth that is created.

The government policy of creating "normal" low to moderate rates of inflation then steadily reduces the purchasing power of those savings, and the farther out we go in time, the less the dollar will buy for us.

But because the interest rates are higher than the rate of inflation, there is still significant wealth creation over time for all of us. So more time still means more wealth, and most financial planning is based on assuming this "Normal/Normal" situation will reliably exist.

The Combined Impact

So we looked at 1) a reduction in interest rates to very low levels – which is currently a quite openly stated matter of governmental policy – and saw that it reduced the rate of wealth creation with our quite normal investment strategy.

And when we separately looked at 2) the effects of a low rate of inflation – which is an equally open matter of governmental policy – it also reduced the rate of wealth creation.

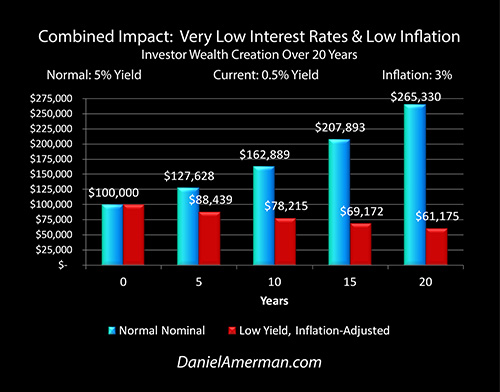

Since we currently have both inflation and low interest rates – what happens when those factors are combined?

The result is that the floor drops out from beneath many traditional investment strategies.

Our final analysis is very straightforward. First, as shown in our "very low interest rates" graphic, we adjust for a lower interest rate, and in five years we have $102,525 in simple dollars instead of the $127,628 we would have had with a historically more normal interest rate.

Next, as shown in our "low inflation" graphic, we adjust for a 3% rate of inflation reducing the purchasing power of each of those dollars to 86.3 cents over the five years. Combine steps one & two ($102,525.13 X .862609) and our future wealth is $88,439. Meaning we actually lost wealth.

And the farther out in time we go, the more wealth we lose. Twenty years out with normal interest rates and the way almost everyone sees things – which is simple dollars – we would expect to have a tidy quarter million plus dollars.

But because of 1) very low interest rates, we only have $110,490, instead of our hoped for $265,330. And when we take into account 2) the dollar in 20 years only having the purchasing power of 55 cents today, then that means the purchasing power of our starting $100,000 in savings is only about $61,000 in the future.

This means that we have lost 39% of what we started with, and we are down 77% compared to what we might have expected to have in normal times.

What we have just looked at is the practical, real world effects of negative real interest rates on average savers over time. And as we saw, interest rates don't actually have to literally be negative (although they are in Europe & Japan, and there is a possibility they could come to the United States).

The same effect is achieved when interest rates are simply lower than the rate of inflation, as they have been in the United States for some years now. Because if the investment return doesn't keep up with the rate of inflation, then our savings become worth a little less in purchasing power terms each year – not a little more – thus giving us a negative return in terms of what our money will buy for us.

For many long-term savers and investors, these results would be shocking, and might even be rejected out of hand on the grounds of being too fantastic, or just plain too foreign compared to what they usually see, and besides – too depressing to think about.

But the truly interesting part is that there is nothing secret, or conspiratorial, or even particularly controversial about what we have just been through. To the contrary, this is all happening in plain sight.

Very low interest rates, somewhat higher rates of inflation, and the use of unconventional monetary policies by central banks to create negative real interest rates are the quite openly discussed story of our times, for the professionals who follow such things. In such an environment the financial math involved in getting to our bottom line results is both reasonably basic and airtight (given the assumptions) – there is nothing controversial there either.

Now what is indeed unusual – is for the average person to understand what is happening, and the potential impact of these policies on their own personal life. If you are a saver, if you are a retirement investor, if you are a current retiree who is drawing down savings to support your lifestyle – then what you are reading here is about you and your own life.

Try this simple test: look at your bank or money market statement, and take a particularly close look at the earnings.

Next take a look at your grocery bill, or health insurance bill, or utility bill, or property tax bill, or the college tuition bill for your child, and compare it to a similar bill from a year ago – or from five years ago.

What almost all of us will see is a personal cost of living that is growing faster than the interest returns on our savings. This is what negative real interest rates look like in our lives. And the reason one can be confident that almost all of the people trying this test with their own bank statements and own bills will see exactly what is described - is that both the low interest earnings and the somewhat greater increase in prices are quite openly stated matters of national policy.

A Deliberate & Possibly Long-Term Situation

Now does this situation exist because governments have some malicious goal of hurting savers? No, I don't believe that at all. Instead there are some practical and very compelling governmental motivations for creating "negative real interest rates".

First, as explored here, many of the most prominent economists in the world, including people like Lawrence Summers and Paul Krugman, strongly and openly advocate these economic policies as being the best way to create economic growth and stimulate job creation. Crucially, what these economists fear and are attempting to fight is what is known as "secular stagnation", with "secular" meaning long term, i.e. ten years or more.

Now if the problem could last for ten years or more, it's reasonable to anticipate that the attempted "cure" could last for ten years or more. And regardless of the reasons for why this is being done, the side effect would be slashed standards of living for retirees relying on their investment income lasting for potentially many years. This could mean an extended reversal of financial planning projections, with wealth destruction replacing wealth creation inside of many retirement accounts, in inflation-adjusted terms.

There are other powerful advantages for governments when it comes to creating near zero interest rates along with somewhat higher rates of inflation, when we consider that the United States, Japan and most of Europe are all not only heavily indebted, but that they all have aging populations with increasing retirement benefit and medical expense. As explored here, the lower the interest rate, the less the debt payments, and the lower the budget deficits. Let me suggest that this creates a long term and major direct conflict of interest between governments and savers.

When we understand this sharp conflict of interest between retirement investors and heavily indebted governments, then we can see that there are "two sides to the coin". One side of "negative real interest rates" is savers losing wealth over time – and the other side is governments actually taking that wealth and using it to reduce government debts (as explained here), in a manner that has been extensively used in the past, through a process which history shows most voters simply don't understand.

Of further crucial importance is that creating negative real interest rates makes owning a nation's currency undesirable, which makes the currency fall in value, which makes exports cheaper, and thereby creates a competitive advantage for exporting goods. Japan previously successfully used this strategy to slash the value of the yen, while boosting both employment and corporate profits. The Europeans are attempting the same thing, and other nations around the world are also cutting interest rates so as not be at a competitive disadvantage, and to hang on to the jobs they have.

In other words there is a current global competition of sorts, in which nations are competing to make their real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates more negative than other nations, in the attempt to gain price advantages on the goods they're selling, as they try to take economic growth and jobs from each other.

With the unfortunate side effect being that they are also essentially competing to see who can most effectively destroy retirement investor wealth creation within their own nations.

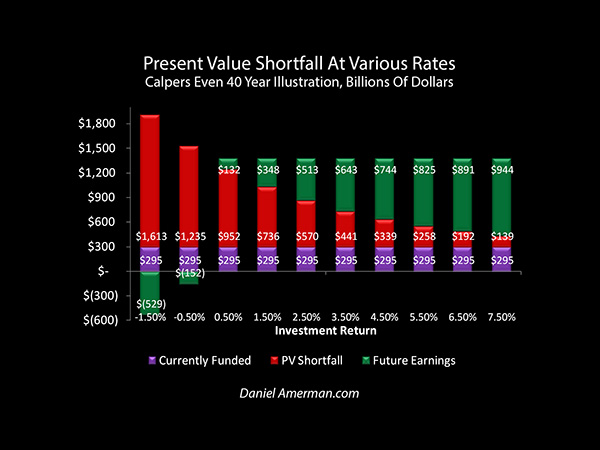

This destruction of investor wealth creation is also affecting the financial solvency of states, cities, school districts and other local governments across the United States. There has been wide coverage of a public pension crisis in the United States, but when low rates are taken into account, the shortfalls are far worse than reported, and could approach the catastrophic.

As explored in the analysis linked here and shown above, the issue is that state and local governments are generally still assuming very high legacy investment rates such as 7.50% for their pensions - and even with those high return assumptions, there are still drastic funding shortfalls, as shown on the far right of the graph. When we move to the left and explore the needed funding with lower returns, the shortfalls (red bars) soar upwards to an extent that could lead to major nationwide tax increases, or reductions in pension benefits - or both.

"Collateral Damage" & Our Future Financial Security

Now again, to be very clear, I don't think that preventing savers from building real wealth or bankrupting state and local governments is the goal of the United States government or other nations around the world. Indeed they would likely much prefer a greater increase in wealth, particularly as more profits means both increased future tax revenues and more future consumer spending. However, when necessary they are willing to allow saver wealth to decrease, because from their perspective, other goals are demonstrably more important.

A good analogy is that of "collateral damage" during warfare, with civilian casualties sometimes being the unintended consequence of soldiers fighting each other. In most wars nations try to avoid killing civilians, but if bombing or shelling the enemy is how the war is won, then they are willing to take the actions that will predictably lead to those civilian deaths.

What should be taken into account is that in this new place in world history, governments don't have just one temporary motivation for creating this difficult environment for investors. Instead, as reviewed herein and developed in much more detail in the linked resources, there are multiple powerful incentives including:

1) attempted economic growth;

2) attempted job growth;

3) reliably reducing the costs of otherwise impossibly large national debts; and

4) either going on the offensive – or just playing defense – when it comes to economic and currency competitions in our globalized world.

And every one of those has the potential of being a long-term motivation.

Which means that our future financial security and standards of living in retirement could end up being "collateral damage" for a long time to come.

Few people realize that the assumed wealth building which traditional retirement investing is based upon can be reversed. Thus they do not realize that we are currently in an environment where as the result of deliberate matters of policy by governments around the world – that reversal has already occurred.

And if we have yields lower than inflation, whether that is from interest rates, or from low dividend yields combined with stock markets falling from current "frothy" heights, then we don't have a mere downward adjustment. Rather, we have a complete reversal where wealth creation becomes wealth destruction. This can change everything that we think we know about investing, as well as every aspect of what we think our future financial security will be.

I believe that there are solutions, and that there are actions we can take to achieve future financial security even in an environment that is destructive to most investors. But they just aren't the usual solutions. To find them, the starting point is education.

***************************************************

Read Chapter One Of "The Homeowner Wealth Formula"

Read Chapter One Of "The Eight Levels Of Homeowner Wealth Multiplication"