Five Little-Known Tools That Governments Use To Reduce Large National Debts - And The Impact On Our Money

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetThe United States government is currently about $20 trillion in debt, which is roughly the size of its annual economy. When it comes to savings and investment decisions, the most common way of dealing with this problem – is to completely ignore its existence. As if to say that this wasn't anticipated in the usual financial planning models, and it looks quite bad, so we will all just pretend it doesn't exist.

For understandable reasons, the national debt seems somewhat abstract to most people. But what history shows us is that how nations reduce debts is deeply personal and even life changing for the individual citizens of that nation. For this has happened before in one form or another many times in many nations over the centuries, and we know that each time the national debt is repaid or otherwise reduced – the personal lives of the people are changed, sometimes dramatically.

Participation in this process is not optional, it is mandatory, and pretending it does not exist – offers an individual no protection whatsoever.

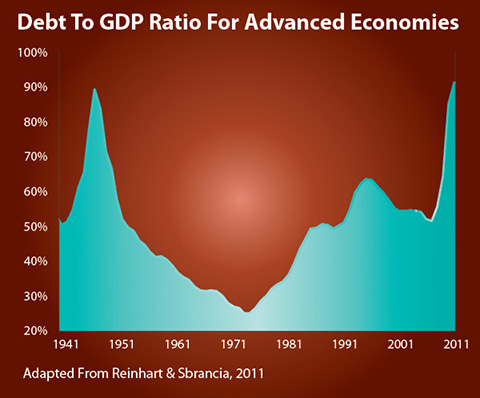

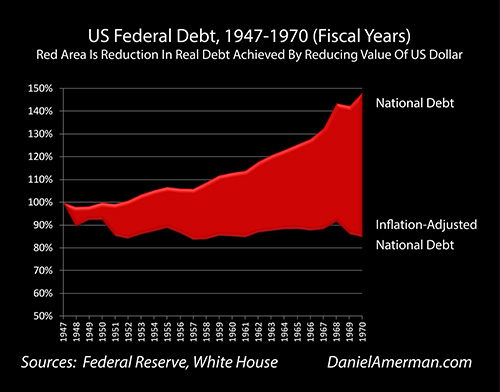

A historical example that is highly relevant for today is what happened with the United States between 1947 and the early 1970s, when the federal debt (measured as a percent of the economy) fell from near 100% down to about 30%.

This reduction in the effective level of debt was no accident and it wasn't free, not by any means. Instead, the powerful tools deployed by the government dominated interest rates and bond markets for decades, and every saver in America helped to pay through a steady decline in the value of their money.

Now the United States is quite suddenly back up to a national debt equal to about 100% of the size of the national economy, and it is far from alone, as many other nations have also become heavily indebted in recent years. While there are unique aspects to the current situation – the core tools for reducing national debts remain the same.

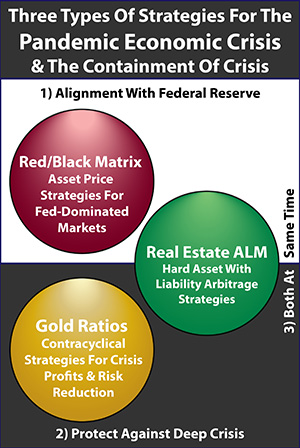

Listed below are the four primary methods which nations use in practice to pay down huge government debts when they have borrowed in their own currency. Which particular method the government chooses could end up being the number one determinant of the value of your savings, as well as your long-term financial security.

1) Decades of austerity with higher taxes and lower government spending. This drastic measure can lower economic growth rates for decades, and fundamentally change investment returns – meaning we all pay together. It is also overt and clearly understood by voters, and can thus have devastating political implications.

2) Defaulting on government debts. This radical option can devastate bond and stock portfolios, bank deposits and retirement accounts – also meaning we all pay together. It is also clearly understood by voters, and thus can have devastating political repercussions.

3) Inflating away the value of the debt through rapidly slashing the value of the currency. Very high rates of inflation rapidly reduce the value of salaries, savings, and retirement accounts – again meaning we all pay together. Because collapsing the purchasing power of savings and salaries powerfully impacts the day-to-day lives of voters, this can have devastating political implications.

4) Use five tools together to create a combination of very low interest rates and somewhat higher rates of inflation that effectively uses private savings to pay down public debts in a manner that is complex enough that the average voter never understands how it works, thus allowing governments to use this potent but subtle method of taking vast sums of private wealth, year after year, decade after decade, with almost no political consequences.

This fourth method that nations use to control or reduce the real value of debt is a process which economists refer to as "Financial Repression", and it is by far the least known or understood by the general public. Not coincidentally, it is also the most common method of national debt reduction that has been used in the modern era. So if the "very low interest rates" part of the recipe sounds familiar – it should.

The use of the five tools of Financial Repression has strong advantages for the government. First, it works in practice – and professional economists understand this very, very well indeed. As published in a working paper on the IMF website, Financial Repression is what the US and the rest of the advanced economies used to pay down enormous government debts the last time around, with a reduction in the government debt to GDP ratio of roughly 70% between 1945 and the early 1970s.

Second – and of crucial importance – is that there was almost no political damage, even while most major nations deployed it over a period of 25+ years to pay down the debts of World War II. So Financial Repression is proven not only to be effective, but in practice to carry very few if any negative political consequences, quite unlike the better known "high drama" solutions of austerity, default or high inflation.

This avoidance of any political cost is also proven by current events since 2010, for even while the major components of classic Financial Repression have been reappearing for the first time in decades in the United States and other nations – there has been relatively little media coverage or general discussion.

To understand this "miracle" debt cure for governments requires understanding the source of the funding. That is, the essence of Financial Repression is using a combination of inflation and government control of interest rates in an environment of capital controls to confiscate much of the purchasing power of a nation's private savings.

Rephrased in less academic terms – the government methodically destroys the value of money over a period of many years, and uses regulations to force a negative rate of return onto investors (in inflation-adjusted terms), so that the real wealth of savers shrinks by an average of 3-4% per year (in the postwar historical example).

Indeed, over time Financial Repression can be every bit as destructive to wealth building through savings and retirement accounts as is austerity, default or high rates of inflation.

And because of the sheer size of the problem – most of the population must be made to participate, year after year. Financial Repression therefore uses an assortment of carrots and sticks to ensure that investors have little choice but to participate – on a playing field that has been rigged against them as a matter of design – even if they are among the small minority who are aware of what is being done to them.

This analysis is part of a series of related analyses, an overview of the rest of the series is linked here.

Understanding Financial Repression

Financial Repression and its devastating impact on retirement investors was the subject of a Bloomberg article, and it has also been previously covered by the Economist magazine, which included the following summary:

"... political leaders may have a strong incentive to pursue it (Financial Repression). Rapid growth seems out of the question for many struggling advanced economies, austerity and high inflation are extremely unpopular, and leaders are clearly reluctant to talk about major defaults. It would be very interesting if debt (rather than financial crisis or growing inequality) was the force that led to the return of the more managed economic world of the postwar period."

The phrase "Financial Repression" was first coined by Shaw and McKinnon in works published in 1973, and it described the dominant financial model used by the world's advanced economies between 1945 and somewhere between 1970 to 1980 (the specific duration varied by nation). While academic works have continued to be published over the years, the phrase fell into obscurity as financial systems liberalized on a global basis, and former comprehensive sets of national financial controls receded into history.

However, since the financial crisis hit hard in 2008, there has been a resurgence of interest in how governments have paid down massive debt burdens in the past. And in 2011 a fascinating study of Financial Repression, "The Liquidation of Government Debt", authored by Harvard economics professor Carmen Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia, was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The paper was circulated through the International Monetary Fund, and to understand why it has caught the full attention of global investment firms and governmental policymakers, take a look at the graph below:

The advanced Western economies of the world emerged from the desperate struggle for survival that was World War II, with a total stated debt burden relative to their economies that was roughly equal to that seen today. The governments didn't default on those staggering debts, nor did they resort to hyperinflation, but they did nonetheless drop their debt burdens relative to GDP by about 70% over the next three decades – and the very deliberate, calculated use of Financial Repression was how it was done.

The Five Tools Of Financial Repression

The specifics of Financial Repression have taken somewhat different forms in each of the advanced economies, but historically they each come down to two fundamental components: A) creating a mechanism for "shearing", i.e., a way to transfer wealth from savers to the government on an extraordinary scale – but without ever explicitly saying that is what is being done; and B) using the government's control over laws and regulations to erect a series of "fences", making it very difficult for investors to escape the "shearing" pen, but again, without ever explicitly saying that this is being done.

As covered in the IMF working paper / governmental tutorial, this combination of shearing and fencing in the postwar era shared four to five core characteristics: 1) inflation; 2) governmental control of interest rates to guarantee negative real rates of return; 3) the funding of government debt by financial institutions; 4) capital controls; and 5) discouraging (or even outlawing in some cases) precious metals investment.

As further explored herein, most of these historical components have reappeared since 2010, in response to the extraordinary rise in government debt levels which resulted from the attempts to contain the damage from the 2008 crisis. The specifics for how the modern version works are in some cases quite different from the well studied postwar example, but they share the following features:

1) Inflation (Shearing #1). First and foremost, a government that owes too much money destroys the value of those debts through destroying the value of the national currency itself. It doesn't get any more traditional than that from a long-term, historical perspective. Without inflation, Financial Repression just doesn't work.

Historically, the rate of inflation does not have to be high so long as the government is patient, but the higher the rate of inflation, the more effective Financial Repression is at quickly reducing a nation's debt problem.

For example, per the Reinhart and Sbrancia paper, the US and UK used the combination of inflation and Financial Repression to reduce their debts by an average of 3-4% of GDP per year, while Australia and Italy used higher inflation rates in combination with Financial Repression to more swiftly drop their outstanding debt by about 5% per year in GDP terms.

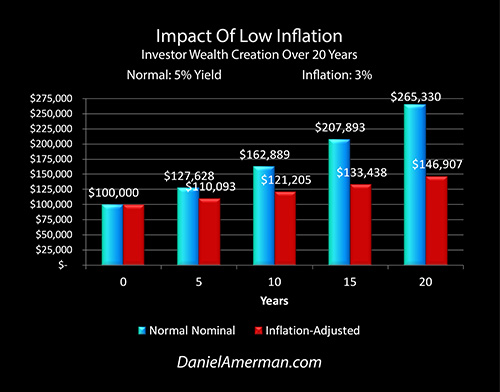

The first blade of the shears is shown in isolation below, and the graphic illustrates how inflation works in combination with normal market conditions, i.e. normal interest rates which are above the rate of inflation.

By themselves, the normal low to moderate "background" rates of inflation that have been created around the world by central banks as a matter of policy for most of our lifetimes are not fun and they do slow the rate of wealth creation. But they don't stop it – normal savings still steadily build wealth over time for most people (at least in pre-tax terms).

Conversely, because governments pay their debts back in dollars (or other currencies) that are worth less than they were at the time of the borrowing, inflation does lower their real cost of borrowing. But there is still a true cost to borrowing, so long as the interest rate paid is greater than the rate of inflation.

In other words, the real building of wealth via interest receipts for individuals requires a real cost of debt for governments.

2) Negative Real Interest Rates (Shearing #2). Shears and scissors each rely on having two blades. Where one blade might be close to worthless in cutting wool or paper, squeezing two blades together can accomplish the same task with remarkable ease and efficiency.

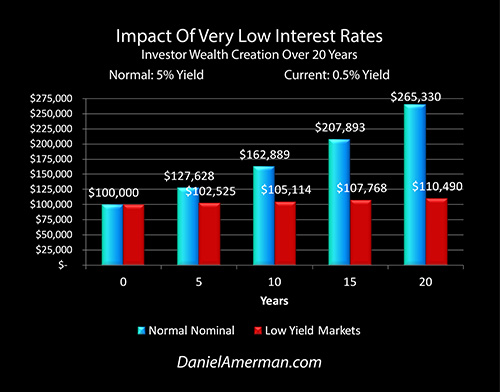

The second blade of paying down government debts with private savings is that of forcing interest rates below the rate of inflation, with near zero interest rates (such as those we have right now) being particularly effective.

The graphic below isolates the second blade, that of very low interest rates. While the blue bars show the usual building of wealth with compound interest during times of normal interest rates, the red bars show how very low interest rates can remove almost all of the financial benefits from long term savings. As all too many retirees and retirement investors have been finding out for themselves in recent years.

But by itself, the second blade of very low interest rates doesn't destroy wealth. There is still positive wealth creation, just at a very slow rate.

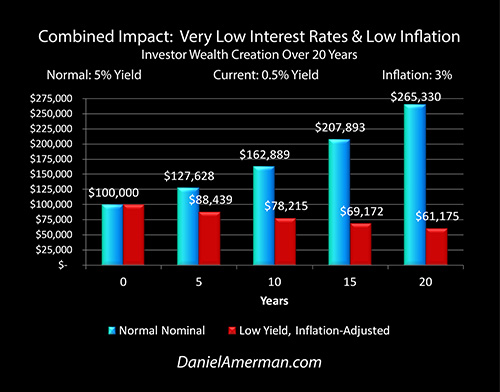

The power of shears and scissors is created by two blades coming together, and the graphic below shows the surprisingly powerful impact on savers when the blade of low to moderate inflation is forced against the blade of very low interest rates.

The real return on investment turns negative for savers, and wealth building inverts into wealth destruction. And the longer the time we savers invest, then the more time the scissors have to work on reducing the value of our savings.

(This is a difficult concept for many people to initially grasp, but the implications can turn retirement planning and other investment strategies upside down. A full length, step by step tutorial on how this works and the multiple reasons why governments are currently creating this situation can be found here.)

Now, in a theoretical world, some would say that governments can't inflate away debts because the free market would demand interest rates that compensate them for the higher rate of inflation. Sadly, this theoretical world has little to do with the past or present real world.

For if we look at the current market, the substantial majority of US government debt is outstanding at rates that are less than even the official rate of inflation. This has been true for some years now, even as it was true (on average) for decades in the past.

The scissors were steadily cutting away at private savings from 1947 to 1970 – and as shown above, the benefit was passing through to the government. The national debt appears to grow (before inflation), and there were many expenses, including the Korean and Vietnam wars. But the two blades were working away that entire time, and indeed grew more powerful as wartime higher rates of inflation increased the sharpness of the blades.

So the national debt in simple (nominal) dollar terms was higher in 1952 than 1949, and much higher in 1970 than it was in 1967. Yet, the inflation-adjusted value of the debt was lower in 1952 than 1949, and lower in 1970 than in 1967. Even as the real value of the national debt was substantially less in 1970 than it had been in 1947.

For that to happen required two blades, and in the past there were formal government regulations that determined the maximum interest rates that could be paid. As an example, Regulation Q was used in the United States to prevent the payment of interest on checking accounts, and to put a cap on the payment of interest on savings accounts.

In combination the two blades did something remarkable.

In the United States and other advanced economies, the national debts were completely out of control by the end of World War II. And by using the two blades of low to moderate inflation and still lower interest rates, the debt was held in place and even forced down in inflation-adjusted terms. Even while economic growth soared. The combination meant the debt monster was tamed.

But there was a price to this "miracle", which was slowly taking real wealth from the savers of each nation in a multi-decade process, which combined two blades and year after year of patience. Which meant year after year of savers losing real wealth, even if the overwhelming majority never understood what was happening, or that it was deliberate, or why it was being done.

Now, Regulation Q is long gone, but government control of short, medium and long term interest rates has nonetheless been near absolute since 2010 in the United States. Even with the very small Federal Reserve increase in December of 2015, interest rates are still far below historical averages, and well within the range where Financial Repression is highly effective.

So long as the Federal Reserve maintains control, there is no need for explicit interest rate controls – or even necessarily for ongoing Quantitative Easing (QE). However, should the Fed begin to lose control, there is a strong possibility that either interest rate controls or another sharp increase in QE will return to the US financial landscape, with similar controls or changes in monetary policy returning in other nations.

***************************************************

Read Chapter One Of "The Homeowner Wealth Formula"

Read Chapter One Of "The Eight Levels Of Homeowner Wealth Multiplication"

***************************************************

3) Funding By Financial Institutions (Fence #1). With this component of Financial Repression, the government establishes incentives for financial institutions such as banks, savings and loans, credit unions and insurance companies to hold substantial amounts of government debt. This can be publicly phrased as "mandating financial safety", instead of the more accurate description of mandating that investments be made at below-market interest rates to help overextended governments recover from financial difficulties.

This funding is sometimes described as a hidden tax on financial institutions, but let me suggest that this perspective misses the important part for you and me. Which is that as financial institutions operating within a country are effectively subsidizing this liquidation of government debt by accepting less than the rate of inflation on interest rates, the gross revenues of all financial institutions are depressed, and therefore less money can be offered to depositors and policyholders.

Then, because financial institutions make their money not on gross revenues, but on the spread between what they pay out and take in, then arguably, the guaranteed annual loss in purchasing power is not absorbed by the financial institutions, but rather passed straight through to depositors and policyholders, i.e. you and me, as further explained here.

The goal of this third element is to make sure that all savers are lending to the government at artificially low interest rates – even though the great majority of them never directly purchase a government security. One way of doing this is savers making deposits which pay very low rates of return, with banks using those very low cost deposits to purchase government debt that also pays a very low rate of return.

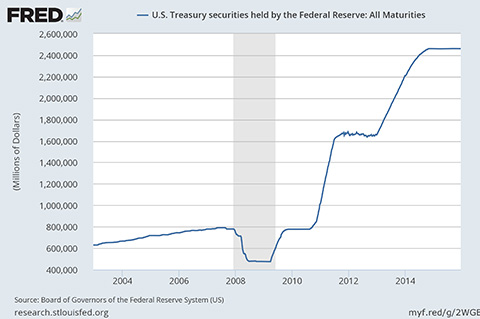

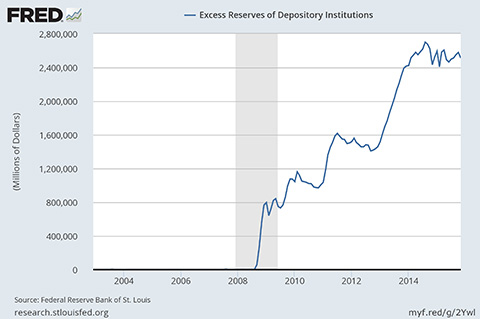

While little remarked upon, that is exactly what has been happening on a multi-trillion dollar scale in the United States, as part of the Federal Reserve's Quantitative Easing program. This can be clearly seen in the graphs below:

The Federal Reserve has purchased about $2.5 trillion in US Treasuries at extremely low interest rates – and it has financed these purchases by borrowing about $2.5 trillion from US banks at (on average) even lower interest rates. Which the banks are financing by paying virtually no interest rates at all to depositors.

On a net basis, the banks and the Fed drop out of the middle, and savers are left financing the US Treasury, with essentially no interest income gained, and an annual reduction in the value of the investment principal within an environment of ongoing inflation. This is a classic example of Financial Repression on an effective basis, even if the specific tools being deployed take a different form this time than they did in the postwar example.

In 2015 and 2016 the forced participation of savers in funding the national debt is substantially increasing again. Fidelity Investments has changed to 100% of their $115 billion Cash Reserves fund, the world's largest money fund, being invested in US government debt as of December of 2015. It is expected that many other money fund companies will also change their policies and invest only in US government and agency securities, because of a change in regulations that will occur in October of 2016.

Now, another textbook element of Financial Repression is that the forced funding of government debt is presented as being mandated by the need to increase safety for the public. As explored here, by tightening the regulations on money funds, another $1 trillion of saver money may soon be exclusively invested in US government debt at very low interest rates. And sure enough the public justification for the regulatory change is that it is needed for the safety of investors, the change is for our own good.

There is still another new twist on keeping saver money going to the government, and that is the recent creation of MyRAs, the user-friendly "my retirement accounts" for small investors, that are presented as being one part of the campaign to help close the income and wealth disparity gap in the US.

To help close this gap the United States Treasury is offering a no-fee and very convenient means for low income and middle class investors to build retirement wealth, with initial contributions as low as $25, and ongoing contributions as low as $5. And of course, the money will always be safe - because the retirement accounts have to be 100% invested in US government obligations, as a matter of law.

4) Capital Controls (Fence #2). In addition to ongoing inflation that destroys the value of everyone's savings and thereby the value of the government's debts, while simultaneously making sure that interest rate levels lock in inflation-adjusted investor losses on a reliable basis, there is another necessary ingredient to Financial Repression: participation must be mandatory. Or as Reinhart and Sbrancia phrase it in their description / recipe for Financial Repression, it requires the "creation and maintenance of a captive domestic audience" (underline mine).

The government has to make sure that it has controls in place that will keep the savers in line, while the purchasing power of their savings is systematically and deliberately destroyed. This can take the form of explicit capital and exchange controls, but there are numerous other, more subtle methods that can be used to essentially achieve the same results, particularly when used in combination.

This can be achieved through a combined structure of tax and regulatory incentives for institutions and individuals to keep their investments "domestic" and in the proper categories for manipulation, as well as punitive tax and regulatory treatment of those attempting to escape the repression. A carrot and stick approach in other words, to make sure that investor behavior is controlled.

For a modern example, we can go back to the Affordable Care Act and one crucial element that was slipped in there with zero public debate. That is FATCA, which has been changing the flow of capital for US citizens on a global basis. FATCA makes it dangerous for foreign institutions to deal with US savers and investors.

They are forced into onerous reporting requirements on the financial activity of US citizens that could be administratively difficult to do, and require changing their internal procedures on a wholesale basis. If they don't comply in exactly the way that the US government wants – then these foreign institutions face potentially severe penalties.

So what are a lot of foreign institutions around the world doing?

They're not allowing US citizens to open accounts. The easiest and most risk-free thing for the bank to do is to simply not open the accounts. Which is effectively a form of capital controls.

Extraordinary Timing

The timing of events in the last few years is fascinating.

When did Quantitative Easing 2 (QE2) appear with the Federal Reserve's overtly taking control of US medium and long-term interest rates, forcing rates ever lower beneath the rate of inflation?

It was November 2010.

When did the surge in bank asset reserves begin with QE2, with an ever greater percentage of bank assets going to the Fed, which used the money to acquire very low- rate US government debts?

That was 2010.

When was FATCA made a matter of law, fundamentally reducing the ability of US citizens to move their money out of the country (albeit not to become effective until 2014)?

That was 2010.

With no press releases, and after an absence of about four decades, three of the core components of Financial Repression almost simultaneously were brought back into play (with the fourth component – inflation – having been there the entire time). Even while federal debt was soaring when measured as a percentage of the economy, returning to levels not seen in almost 60 years. Indeed, debt levels have not been this high since the last time Financial Repression had been used.

Coincidence?

5) Precious Metals Controls (Fence #3). Now there is a fifth component that is very important as well. This one's a little more optional, but it's part of classic Financial Repression in the United States as well as the UK and other nations.

And that is if the government is creating inflation, and as a matter of law it's not allowing citizens the ability to protect themselves from that inflation, then investors will be tempted to seek refuge in precious metals.

So the fifth component of classic Financial Repression is to either make illegal or discourage investment in precious metals. To some extent that's already true in the US when we look at our collectibles tax treatment as compared to other investments, which strongly penalizes investments in precious metals, as explained here.

At this stage, there have been fewer changes with regard to precious metals than with the other categories of Financial Repression. However, it is worth keeping in mind that the more successful precious metals investors are in dodging Financial Repression – then the more likely the return to Financial Repression for precious metals investors. After all, the underlying theory is based upon not allowing savers to escape the pen.

A "Low Drama" Approach To Systematically Cheating Investors

The governments of the world are in deep financial trouble, and would naturally prefer to avoid the "High Drama" approaches of overt global defaults, very high rates of inflation, or comprehensive austerity coupled with massive tax hikes – if possible. For each of those radical routes is highly unpopular, and could lead to political turmoil that would remove the decision makers and the special interests who support them from power. A more subtle approach sounds far more attractive, particularly since it has worked before over a period of decades, with an almost boring lack of political turmoil.

To get out of trouble by way of Financial Repression, the governments must wipe out much of the value of their debts, without raising taxes to the degree needed to pay the debts off at fair value. In other words, they must cheat investors on a wholesale basis. There is nothing accidental going on here, all that is in question are the particulars of the strategies for cheating the investors, meaning the collective savers of the world.

Again, the time-honored and traditional form that heavily-indebted governments use to cheat investors is to devalue the currency. Create inflation, and tax collections will rise with that inflation but the debts won't, and meanwhile the savers of the world will be paid back in full with currency that is worth less than what was lent to the governments in the first place.

When many people think of inflationary dangers, they think of high rates of inflation, perhaps 10% per year or more. They take a "High Drama" approach, and think that if rates of inflation are more moderate, then there isn't that much to worry about.

Ironically, however, this belief could not be more mistaken, for what history shows is something else altogether. "Moderate" rates of inflation have historically been quite effectively used over a period of decades to redistribute wealth from individual savers to national governments on a massive scale with virtually no political costs – because the taking of wealth is being done slowly, subtly, and through a process that the general public has historically not understood.

Learn more about the rest of the free book.

***************************************************

Read Chapter One Of "The Homeowner Wealth Formula"

Read Chapter One Of "The Eight Levels Of Homeowner Wealth Multiplication"