Why Is The Federal Deficit Really Falling?

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Below is the 2nd half of this article, and it begins where the 1st half which is carried on other websites left off. If you would prefer to read (or link) the article in single page form, the private one page version for subscribers can be found here:

The "Crowding Out" Of Private Economic Growth

What has happened over the last three fiscal years is in reality not only quite different from what is being publicly presented – but it was also entirely predictable given the constraints facing the government.

In 2010 – the starting year for this analysis – I first published an article (since updated and available here) titled "High Government Deficits "Crowd Out" Stock Market Returns", in which I made the case that we should anticipate that because an aging population meant an increasing percentage of people would be receiving retirement benefits each year – that combined with other rising transfer payments, the percentage of the economy consumed by the federal government must rise.

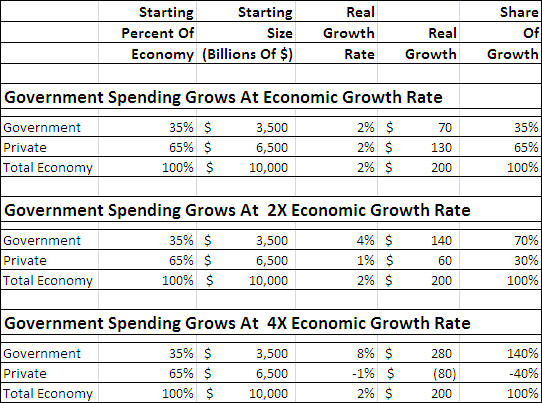

This is just common sense. There is only so much total economic growth available. And if the government's share of that economic growth is rising at a rate higher than total economic growth – then economic growth in the private sector must be falling relative to total economic growth.

Indeed, as shown in the chart and developed in much more detail in the linked article originally from 2010, this anticipated increase in government spending must necessarily be matched by a decrease in private dollars available for consumption, standard of living and investment growth for the rest of us.

But it is somehow not taken into account in either government press releases or in most mainstream financial analyses of expected investment performance. If it were, and the public better understood these fundamental relationships, there would be a demand for major changes in the most common investment strategies.

Now of significant note is that whereas this 2010-2013 analysis focuses only on federal tax receipts, the above chart from 2010 (and the article, "Crowding Out") factors in state and local government taxes as well. And the more levels of government that are included, the lower the governmental spending growth rate that is needed to consume all private sector economic growth.

Tweaking Inflation Rates

An important related question to consider is whether we accept the current quite low official government rates of inflation.

If you find that your personal expenditures for such things as grocery store food, restaurants, gasoline, utilities, college education, and healthcare are increasing at a rate in excess of the official 1.5% or 2% per year, then the effect on you is much greater than what is shown here.

If a higher rate of inflation is what you are personally experiencing, and is even 1.5% greater than the official rate used herein – then most certainly no real growth occurred in the economy in after-inflation and after-federal tax terms for all three years between 2010 and 2013. We would still have had positive growth in the overall economy (so long as the true rate were less than 2.3% above the official rate), but every bit of the economic growth would've been consumed by the government in spending – and in partially closing the deficit.

Leaving no growth whatsoever for the overall private sector.

Another issue affecting results is that official deficits are based on government accounting, which is politically designed to allow the government to report lower deficits. Apply the same type of accounting used by private corporations and individuals, then as has been widely reported (including here), government deficits soar far beyond what the federal government indicates, and the situation is even more extreme when it comes to the share of the future economy that will be taken by the government.

While the limited goal in this one analysis has been to "truth test" the government's recent optimistic assertion – through using only the government's own numbers – those three additional factors of a likely higher real rate of inflation, the inclusion of state & local government taxes, and the use of governmental accounting need to be at least considered as well. Relatively small movements in any one of these categories are sufficient to entirely consume the slim 4.1% after-inflation and after-tax increase in the private sector over the three fiscal years from 2010 to 2013.

Investment Implications

As my long-time readers know, for many years now I've been advocating an approach to preparing for the future which is not mainstream, but neither is it "gloom and doom" – it is just common sense and reality-based.

As I've long been pointing out as a basic matter of demographics in the United States (and many other nations), the simple fact is that we have an aging population that has been promised expensive retirement benefits, and this means that the government's share of the economy is likely to be steadily rising.

If the government is taking steadily more of the economy, that leaves steadily less of the economy available for private consumption and private growth. And slashing private growth rates slashes the wealth that can be created by private investments.

And if an aging population by itself translates to a lower overall economic growth rate – as many economists believe – that exacerbates the problem.

Moreover, if we accept the historical evidence that deeply indebted nations usually experience lower overall economic growth rates – that further exacerbates the problem.

However, that does not mean that this will all take a highly dramatic form. Nor is there any more reason to believe it will dominate the headlines five or ten years from now, just as it isn't appearing in the headlines right now. Instead, it is likely to be more of a slow but nonetheless irresistible background force, which in the interests of the government and most of the investment industry, the majority of the public will neither be aware of nor understand.

The heart of the issue for investors is that all across the nation – and in analogous situations in other nations – we're being told that if we invest in stocks we will benefit from the growth in the economy on a predictable basis based upon decades of past performance.

However, as total stock returns are the combination of dividends and capital gains – and because dividends are currently quite low by historical standards – this means that capital gains in the years ahead will need to be unusually high if stocks are to perform at historical levels. And given that the primary driver of capital gains for the market over time is supposed to be economic growth, this means that economic growth will in turn need to be unusually high if historic stock returns are to be delivered.

Meanwhile, deficits are being lowered and the government is being funded by appropriating a disproportionate share of that economic growth.

Which means that disproportionately less is available for private investors.

Which naturally should be expected to substantially reduce many investment returns over the longer term.

Another crucial issue is, as my readers know, that economic growth is not the only place where the government is effectively competing with investors for resources.

That is, the biggest reason that the deficit is now below $1 trillion is that interest rates are by historical standards very, very low. If interest rates were to go up substantially – then the deficit explodes.

Therefore, as previously covered in other analyses here and here, the federal government has an overwhelming motivation to keep interest rates very low. The efforts that a deeply indebted and financially stressed government makes to keep interest rates low – suppress interest rates for the entire nation.

In other words, the interests of the government are in some crucial ways in direct competition with the interests of traditional long-term investors when it comes to interest rates, as well as who gets to keep what economic growth there is. What helps hold deficits down are low interest rates, which simultaneously reduce interest payments to investors from bonds, annuities, CDs and money market funds.

So when we look at both stocks and bonds, the two traditional legs that long-term investing in general and retirement investing in particular are usually based upon, in both cases because we are investing for an environment where an already deeply indebted government must pay for new expenditures that are rising at a rate faster than the economy as a whole, we are likely to be outcompeted by the government for yield with both stocks and bonds.

This is not necessarily about gloom and doom, nor is it end-of-the-world talk – this is simply the reality of an aging population with slowing growth rates.

Unfortunately, most investors are not basing their strategies on this reality. Instead they are being encouraged to invest for a future that consists of the past endlessly repeating itself, with stocks and bonds delivering yields over the decades much like they did in the 20th century.

In other words, implicitly they are investing for a world which has two economies. There is one economy that is increasingly dominated by the government, which is consuming economic growth even while suppressing interest rates. And then there is that second economy of blue skies and clear sailing, where investments reliably deliver results like they did in days long gone by.

But given that there is only one economy, this quite common approach of investing for the past may perform very badly indeed in a future of much lower private sector growth and low interest rates.

There are alternative approaches, however. Which begin with accepting that the present and the future are different from the past, and quite likely to continue to be so. Which means that everything changes when it comes to finding the best strategies.

Risks, returns and opportunities are very different in government-dominated economies – and positive results can become much more difficult to obtain. Which strongly increases the benefits of understanding this new environment.