The Great Game, Gold Arbitrage & Three Little Pigs

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

The Great Game

An astute reader from Atlanta named Ken wrote the following in a letter to me:

"It seems that the game plan (for financial heavyweights) is to buy assets, real things that can't be papered away by the government, and pay back with depreciated dollars."

Ken gets it. Ken understands the Great Game as it is being played at the highest levels of our monetary system. The Game has two halves: going long the real, and short the symbol. That is, going long real assets by owning them, and going short the dollar and the financial system by selective and advantageous borrowing. That way if you are a hedge fund manager, CEO or “private equity” investor who has essentially gambled the world monetary system on your speculations, and you collapse the financial markets and the value of the dollar when you guess wrong – you don’t jump out the office window. Instead, you enjoy an extraordinarily lucrative early retirement.

That's because you still own the real – and the destruction of the value of the dollar just means that you no longer have to pay back most of what you borrowed to buy the real (in inflation-adjusted terms).

As an example, a financial “heavyweight” borrows $1 billion to buy $1 billion in real assets. If asset inflation in real terms occurs and the asset climbs to $1.5 billion, he can then sell the asset, pay off the $1 billion loan, and walk away with half a billion.

If the credit bubble he used to buy the asset unwinds and destroys 80% of the value of the dollar in the process -- no problem! The price of his real asset climbs with inflation, so it is now worth $5 billion in future dollars, even while he still only owes $1 billion.

So he sells the asset, pays off the borrowing, and walks away with $4 billion as a reward for his contribution to the credit bubble. In inflation-adjusted terms: the asset maintains its value at $1 billion, inflation shreds 80% of the value of the $1 billion loan, knocking it down to $200 million, and thereby creates $800 million in equity in real terms. There are a number of simplifications in this example, but that is the essence of the Great Game.

The question then is – what is your personal reaction to this scenario? One response is to loudly and frequently express outrage that this situation is allowed to exist. That is a most justifiable response.

Another response is to take your piggy bank and try to hide it somewhere where it won't be destroyed by the games other people are playing. That is a most understandable response.

Still another response is to say: "I wish this weren't happening, but it is, so how do I personally profit from it?” That is the most advantageous response.

THE THREE LITTLE PIGS

That "personal profit" part likely sounds pretty good. But, if we personally don't have the millions and billions to directly access the capital markets and play the Great Game – how can we participate in the profits? To find an answer, we are going to travel back in time, re-examine an old children's story, and explore the little-known key to how millions of households successfully turned inflation into net worth. The time we will travel back to is the last time inflation raged out of control in the United States, when the dollar lost 57% of its value between 1972 and 1982.

The children's story is The Three Little Pigs, with the big bad Wolf being played by Inflation. Playing the roles of The Three Little Pigs are three brothers: Dave, Mike, and Jim. Each brother accurately sees the Wolf of Inflation on the way, and each tries to protect himself by building a different kind of financial "house". That is our first variant on the children’s story; we are going to ignore the millions of households who don’t believe the Wolf is coming, and who thus lose their savings portfolios of straw and wood as a result. Instead, we will concentrate on historical brick-house performance.

The three brothers each inherited $9,000 in 1972. Each had already taken out a mortgage to buy a home in 1969. There had already been some inflation, and the value of each house by June of 1972 was up to an exactly average (rounded national median value) of $18,000, with a $9,000 mortgage outstanding. So the story begins with each brother having $9,000 in cash, a $9,000 mortgage and $9,000 in home equity.

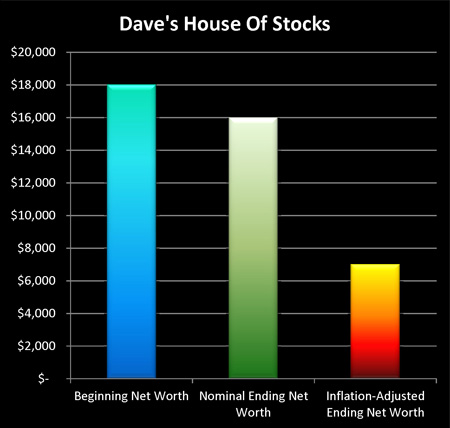

DAVE AND HIS HOUSE OF STOCKS

Brother Dave was a well read and educated kind of guy, and being financially sophisticated when it comes to conventional financial planning principles, he knew that common stocks were not only the key to long term wealth, but were an excellent hedge against inflation. So our first Little Pig sold his house, got his $9,000 in equity, and combined it with his $9,000 inheritance to buy $18,000 in stocks.

As a sophisticated conventional investor, Dave knew better than to try to beat the market, so he instead bought a well-diversified basket of common stocks, one that precisely tracked the performance of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The Dow was at 929 in June, 1972, but after ten years of inflation averaging 8.73% -- it was at 812 in June of 1982. This meant that the value of Dave’s portfolio had fallen from $18,000 down to $16,000, a loss of 13% over the ten years (the more precise value would be $15,733, but we are generally rounding to the nearest thousand).

Dave was disappointed to see that his stocks had not done as well in fighting inflation as the finance professors had indicated they would, even in nominal terms. However, Dave was downright horrified when he remembered to do what the newspapers so often forget, and converted his stock price performance to real dollar (inflation-adjusted) terms.

By 1982, after ten years of inflation, the dollar was only worth 43 cents in terms of 1972 dollars. So when Dave took his $16,000 ending value in 1982, and converted it to constant 1972 dollars, he found that his ending stock value was only $7,000. In real terms, Dave had managed to lose $11,000 of his $18,000 starting investment – meaning a real loss of 62% – by relying on common stocks to beat inflation.

(The percentages are based on the actual numbers, not rounded to the nearest thousand. The cost of housing for Dave for ten years, along with the receipt and reinvestment of stock dividends are two of the many items left out of this simple educational illustration.)

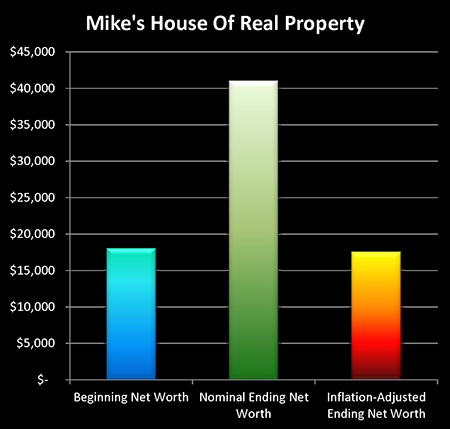

MIKE AND HIS HOUSE OF REAL PROPERTY

Brother Mike was a cautious kind of guy who didn’t believe in either the stock market or being in debt, but did believe in the value of real property in times of inflation. So our second Little Pig took his $9,000 inheritance, paid off his mortgage, was now debt-free, and hunkered down in his $18,000 house to await the storm. The Wolf of Inflation blew hard and battered the dollar, the economy, the markets and personal savings for ten long years – and by June of 1982, Mike’s house was now worth $41,000, again the exact national average. So, Mike made an apparent profit of $23,000, or 125%.

Mike felt pretty good about how his house withstood the ravages of inflation. Until he ran the numbers and took into account that a 1982 dollar was only worth 43 cents in 1972 dollar terms. Adjusting for inflation, Mike’s $41,000 house was only worth about 17,500 in 1972 dollars – he had lost $500 (or 2.5%) in real terms over the ten years.

Now, this is not to say that Mike did poorly. He almost maintained the real value of his investment during the most powerful bout of inflation in recent American history, and unlike his two brothers, he did have a place to live for ten years without making mortgage or rent payments, which freed up money that he could have then used for investing. But owning the house itself on a debt-free basis did not directly make him money in inflation-adjusted terms.

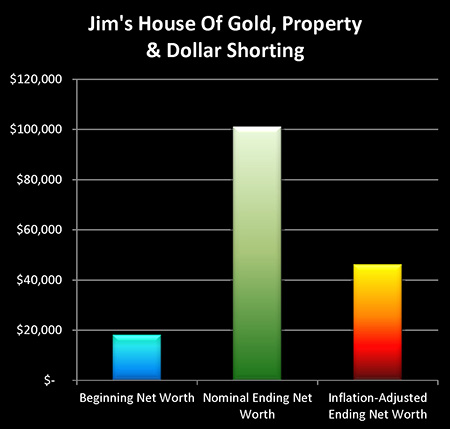

JIM AND HIS HOUSE OF GOLD, PROPERTY & DOLLAR-SHORTING

Brother Jim liked gold for fighting inflation, and he liked real estate too. Our third Little Pig wasn’t thrilled with debt either, but he did have a bit of a brainstorm. “Jimbo,” he thought to himself, “if I am convinced that the value of the dollar is going to be plunging – why should I pay off my debts now, when the dollar is expensive, when I could wait and pay off my debts when a dollar is cheap?” So, Jim chose not to pay off his mortgage, but instead refinanced it up to $14,400, using a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, which brought it up to an 80% loan-to-value. He then took the $5,400 he pulled out of his house equity, added in the $9,000 he inherited, and used the combined $14,400 to buy 232 ounces of gold, at the then-current price of about $62 an ounce. (The price is as of June, 1972, to keep comparability with the housing and inflation numbers. Gold did not become legal for individual Americans to own for investment purposes until January 1, 1975, but we’re treating it as if they could, to properly capture the inflationary period over the full ten years.)

So Brother Jim had a starting position in 1972 of owning an $18,000 house, owning $14,400 in gold, and owing $14,400 in a long-term and fixed rate mortgage. The Wolf of Inflation huffed, and puffed and blew hard for ten years, and three major financial changes worked together to dramatically change Jim’s net worth by June of 1982. The first change was that just like Brother Mike, the value of his house had climbed to a nationally average price of $41,000. This meant that it did not quite keep up with inflation, but lost about $500 in real terms.

The second financial change was that owning gold grew quite popular after ten years of sustained high inflation, and by June of 1982, gold was up to about $315 an ounce. This meant that Jim’s 232 ounces were worth about $73,000, which is a nominal profit of $59,000, or about 407%. When Jim adjusted for inflation, he was much happier than Mike, for even after discounting 57% for the decline in the dollar, Jim’s initial $14,400 had turned into $32,000 for a profit of 120% in real terms.

The third financial change was that unlike Mike or Dave, Jim had borrowed the equivalent of 80% of his net worth in a fixed-rate mortgage, that effectively constituted a long-term, tax-advantaged and relatively low-cost short on the value of the dollar. By 1982, inflation had shredded 75% of the value of that mortgage, including both the depreciation in the value of a dollar, and the value of having a long term loan locked in at a far below-market rate. So Jim’s debt had fallen from $14,400 down to $3,000 in real terms.

JIM’S WEALTH & ITS SOURCES

Adding it all up, Jim’s net worth in nominal terms went in ten years from $18,000 to $101,000, when we add the $73,000 in gold to the $41,000 in house value, and then subtract the $13,000 in remaining mortgage outstanding. When we look in nominal dollar terms, it appears that Jim made his money in gold and housing, while the mortgage paid down a bit. However, when we adjust all three factors into real dollar terms, we see that:

Jim made about $17,500 on his gold investment (1972 dollars)

Jim lost about $500 on the value of his house

Jim made about $11,000 through inflation shredding the value of his mortgage (and a bit of mortgage amortization)

When we add these up, we find that Jim’s net worth had climbed from $18,000 up to about $46,000 in real terms, giving him an inflation-adjusted total return of about $28,000 (155%) over the ten years of sustained inflation. Jim simultaneously went long the real and short the symbol, and when the symbol (the dollar) then had a loss of confidence and plunged in value – Jim’s net worth soared as a direct result.

While the first Little Pig lost 62% of his net worth investing in common stocks in inflationary times, and the second Little Pig lost 2.5% in real terms through owning real estate – our third Little Pig turned those problems into a 461% nominal profit, and a 155% real dollar profit. As an individual of quite limited resources, Jim played the Great Game and played it well.

THE GREAT IRONY

Gold did excel during the inflationary 1970s and 1980s, as it may again if another round of major inflation befalls us. This performance is well known. The irony, however, is that gold is not where most households made their money. As documented in my book, The Secret Power Within Your Mortgage, when we track exact national averages from 1972 to 1982, the average homeowner saw their real equity grow from 25% of their mortgage amount to 500% of their mortgage amount as a direct result of being effectively short the dollar during a sustained period of relatively high inflation – even while real estate prices were slightly declining on an inflation-adjusted basis.

This extraordinary growth is far from theoretical. The inflation-driven destruction of most of the value of the outstanding mortgages was what nearly destroyed the Savings & Loan industry back in the 1980s, and I spent years as a young investment banker trying to help financial institutions survive the massive damage. Indeed, this event constituted one of the largest transfers of wealth from institutions to individuals in American history.

You likely know someone who held onto their house for decades over this era and became “house rich” as a result, enjoying the benefits of a huge equity in their home even as they made little $50 or $100 monthly payments long after the national average mortgage payments had moved to over $500, and then to over $1,000. Yet, to the extent people think about it at all, they often mistakenly believe this increase in personal wealth was a result of the run up in home values (which merely more or less kept pace with inflation), rather than inflation effectively forgiving most of their largest debt and making most of their payments.

CHECKING THE BACK DOOR

Sometimes if the front door is locked, you need to check the back door. If direct asset purchases are problematic, and your net worth is equal to your assets less your liabilities – liability management becomes your back door. This back door is standing wide open - at interest rates that have been manipulated by the Federal Reserve to be far below free market rates - and constitutes a highly effective way of shorting the value of the dollar in a long-term and tax-advantaged manner.

It is this back door that created enormous amounts of homeowner wealth the last time inflation went out of control in the United States. It is creating the back door within investment strategies that is key to the Great Game as it is being played right now, for when the Game finally ends – the back door of inflation shredding the value of the debts is what will allow many of the people who created the problem to walk away wealthier than ever. In some cases this will be accidental (as it was for most homeowners in the 1970s), but for the more astute investors this is quite deliberate. As it needs to be for you, if you are to enjoy the same protections and profit potential.

When you put a “back door” on your long-term wealth preservation and creation strategy, then you have a 1-2 combination with both assets and liabilities. The assets you lead with are then a matter of choice, and the effectiveness and costs of this strategy will vary widely with that choice. Gold, the choice for Jim illustrated here, has powerful advantages for near term and major inflation – but is also quite expensive in terms of cost of carry, as you won’t have interest, dividends or rental income to offset the mortgage payments. There are pros and cons to gold as there are with a diverse range of alternative investments.

A Puzzle For Turning Inflation Into Wealth Mini-Course Readers

Let’s take a minute and go back over the results achieved by Jim when he owned a home, borrowed with a mortgage, and bought gold. By purchasing gold during a time of economic turmoil, and by buying at $62 an ounce and selling at $315, he made a 407% return during a decade when the stock and bond markets were being pummeled. Even after discounting for a dollar only being worth 43 cents by the end of that decade, Jim still made a (pre-tax) real return of 120% on his investment.

Results of this type, from the last time stagflation punished the United States, are exactly what many investors are currently seeking through investing in gold. It is also interesting to note that these superior results were achieved during a decade when real estate values were (on average) falling in real terms.

So what would have happened if Jim had skipped the money-losing real estate investment, and put everything he had into gold, during a decade of outstanding gold performance?

If Jim had sold the house, taken his entire $18,000 and bought gold at $62 per ounce in June of 1972, then he would have owned 290 ounces of gold. His $18,000 would have become worth $91,000 by June of 1972, for a monetary gain of $73,000, which would have equaled a percentage gain of 407%. His investment would have become worth a little more than $39,000 in inflation-adjusted terms, for a real gain of 120%.

In other words, by skipping the money-losing real estate investment with 80% mortgage financing, and putting everything into gold during a time when gold excelled as an investment – Jim would have earned $7,000 less in real (after-inflation) terms, and dropped his simple total return from 155% down to 120%. Remember, Jim only started with $18,000 between cash and house equity - so $7,000 in additional real profits is a tremendous boost.

This is of course on a pre-tax basis, with a very simple analysis. When we fully include the inflation tax benefits and the value of having a place to live for ten years, then Jim’s multiple asset strategy outperforms a gold-only strategy by a much wider margin, even after we have fully incorporated the effects of making mortgage payments over the ten years. Indeed, as we saw in our earlier reading, "Creating Wealth With An Inflation 'Tax Shelter'", when we add the benefits of the inflation tax shelter, then the real estate / mortgage combination alone would have produced after-tax and after-inflation benefits equivalent to a conventional investment earning about 22% per year.

Rephrased then, if we could travel back in time with what we know now, the correct answer to gold versus real estate in 1972 was neither gold nor real estate – but both. This is true even when we assume a foreknowledge that gold would have a stellar performance, and that real estate would not quite keep up with inflation.

Multiple-Asset Turning Inflation Into Wealth Strategies

What we just saw was an example of making more money in inflation-adjusted terms by putting 56% of your assets into an asset that loses money in real terms, instead of 100% into an asset that more than doubles your investment in real terms. How and why this works is beyond the knowledge of most people. Indeed, it might seem counter-intuitive - if not impossible - to most individual investors, and that might have included you before you started this course.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

If you find these "eye-openers" to be interesting and useful, there is an entire free book of them available here, including many that are only in the book. The advantage to the book is that the tutorials can build on each other, so that in combination we can find ways of defending ourselves, and even learn how to position ourselves to benefit from the hidden redistributions of wealth.