Deadly Deflation Myths

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

As will be demonstrated herein, using both historical and present-day events, key aspects of current deflationary theory can be characterized as the combination of 1) an absurdity; 2) a misunderstanding; and 3) an oversimplification; all working together to create 4) a serious danger for investors.

Few questions are of greater concern for investors than: "will it be inflation or deflation that will dominate the coming years?"

This has been a topic of ongoing and sometimes heated debate. However, could it be that the correct reply to this pivotal issue is... "wrong question"?

The very common belief that it must be one or the other – either inflation or deflation – is one of the myths that we will explore. Indeed, the premise behind the question itself is dangerously mistaken, and investors believing those to be the only two choices face multiple kinds of unnecessary risks for years and even decades to come.

First, let me clarify that if one goes by the common and very simplified use of the term "deflation", then I am not a "Deflationist". For I believe that the value of all of our money is very much at risk in the years ahead.

However, I am indeed an asset deflationist, and have been so for a long time. That is, I strongly believe that decreases in the value of investment assets in purchasing power terms is one of the largest dangers facing investors in the years ahead.

Now the distinction between the simple term "deflation" and the much more precise term "asset deflation" is no mere technical one. And indeed, understanding the difference has the potential to transform the way one interprets the financial world of both the past and present, and could lead to potentially quite different strategies for future investment.

In this two-part series, we will:

1) Uncover the elementary "apples and oranges" mistake at the heart of many Deflationist theories, which is the failure to distinguish between currencies backed by tangible assets – and currencies which are not (such as today's US dollar);

2) Show that the central monetary lesson of the US Great Depression of the 1930s is not, as commonly believed, the unstoppable power of deflation. Instead, history proves the direct opposite, which is that a sufficiently determined government can smash monetary deflation and replace it with inflation – at will and almost instantly, even in the midst of a depression;

3) Refute the very common but dangerously mistaken belief held by many investors, which is that asset deflation – the falling value of assets in purchasing power terms – somehow protects the purchasing power of their (symbolic) money, so they no longer have to worry about inflation; and

4) Reject the commonly-held perspective that inflation versus deflation is some sort of neutral, market-driven battle between economic forces, and recognize that rather than a neutral playing field, there is an arena designed and managed by the government in which the predominant force is deliberate governmental interventions. For the government has overwhelming incentives to create a particular range of outcomes for its own benefit, each of which will systematically strip wealth from investors in a manner which few investors will fully understand – meaning few will be able to defend themselves.

The Great Depression: A Succinct Statistical Summary

The Dow Jones Industrial Average reached a peak of 381 on September 3, 1929. By July 8, 1932, it had hit its floor of 41, a plunge of 89% in less than 3 years.

The United States Gross Domestic Product was $103 billion in 1929. By 1933 it had fallen to $56 billion, a decline of 46%.

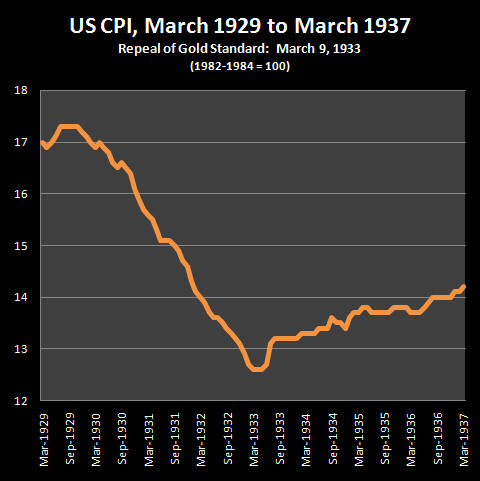

Accompanying the free fall in both the economy and the markets, price levels were falling as well – meaning that the value of a dollar was rising rapidly. The Consumer Price Index was at a level of 17.3 in September of 1929, and by March of 1933 had fallen to a level of 12.6. So what had cost a dollar in 1929, only cost 73 cents (on average) by 1933. This 27% deflation – or decline in the average cost of goods and services – represented a 37% increase in the purchasing power of a dollar.

For some, the effect of this deflation was to increase both their wealth and their standard of living. These are the people who had substantial money in savings – whether it was physical cash, or fixed-denomination financial assets that had survived the economic turmoil (such as accounts in banks that did not go bust), or the bonds of companies that did not default. For these individuals, all else being equal, their standards of living rose because they had the same number of dollars, and each dollar bought more than it had previously.

However, for most of the nation (and the world), this increase in the value of a dollar was achieved at great cost. The reason behind the increase was that dollars had become scarcer for businesses and most individuals. The destruction of the banks and much of the financial markets had dried up access to money on attractive terms. Widespread unemployment meant fewer dollars available to buy goods and services, which drove down the prices, which is what dropped the Consumer Price Index.

Most importantly, the deflation was not independent of the plunge in the markets and economy, nor just a result of it. Instead, as most economists agree, this monetary deflation was actually a reason why the Great Depression got as bad as it did.

Because there was not enough investor money, the source of funding for growing businesses was gone. Because they didn't have enough money, consumers were not spending. And because there wasn’t enough spending, businesses had to lay people off. Which further reduced consumer spending.

The nation was caught in a vicious deflationary cycle, which it seemingly could not break out of.

Yet, the United States did break out of the deflationary cycle, as illustrated in the graph above. After rapidly plunging for about 30 months, with the CPI seemingly in free fall and not able to find a floor – there was an abrupt turnaround. Not only was a floor found, but an immediate cycle of inflation replaced the seemingly unstoppable deflation. The nation essentially “turned on a dime”, from deflation to inflation instead. It is a cycle of inflation that has continued until this day.

What happened?

March 9, 1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933. He came into office with a mandate and agenda to stop the Depression, and that meant breaking the back of the deflationary spiral. His actions were swift, beginning with a mandatory four-day bank holiday imposed the day after his inauguration.

Five days after Roosevelt took office, on March 9th, the Emergency Banking Relief Act was passed by Congress. This was the first in a series of executive orders and bills that would take place over the following weeks and year, and would cumulatively take the United States government off the gold standard – and would also effectively confiscate all investment gold from US citizens at a 41% mandatory discount.

Prior to this time – from 1900 to 1933 – the US government had been on a gold standard, and had issued gold certificates. In a matter of days in March of 1933, there would be a radical change – a veritable 180 degree turn – that would not only repeal the gold standard, but effectively make the use of gold as money illegal in the United States.

Fallacy One: Confusing Apples & Oranges

There is a common simplification that people make when they look at money over time. They think that a dollar is a dollar, even if the purchasing power has changed a bit. This is a quite understandable mistake, particularly if your profession does not involve the study of money.

When we look back over history, however, nothing could be further from the truth. This assumption instead reflects an elementary logical error which could be quite dangerous for your personal future standard of living if it leads to your drawing the wrong conclusions.

The term “dollar” is only a name (the same holds true for the “pound”, “franc”, “peso”, “mark”, and all other currencies).

What matters is not the name, but the set of rules – or collateral – that back the value of the currency during a given historical period. When we look back over long-term history, then sometimes it is gold, sometimes it's silver, sometimes it's both – and sometimes it is something else altogether. (As a creature of politics, money has always been of a complex and quite variable nature, given enough time.)

So when we say history “proves” something about a currency, we need to be very, very careful that we are comparing apples to apples, rather than apples to oranges. For instance, when we look at precious metals-backed currencies, the deflation of 1929 to 1933 when the US was on the gold standard was nothing new. It was just the latest development in the ongoing cycle of inflation and deflation that characterizes this type of currency.

Indeed, there were four major deflationary cycles during the century before Roosevelt ended the domestic gold standard. And the deflations of 1839-1843 and 1869-1896 were each much larger than the deflation of 1929-1933, with the dollar deflating roughly 40% in each of those earlier deflations.

This deflationary history does not, however, reflect the value of the “dollar” (as we currently know it) bouncing up and down, but rather the value of the tangible assets securing the dollar bouncing up and down around a long term average.

Going off the gold standard wasn't anything new either. Many nations have gone through periods, particularly during wars, when more money was needed than there was gold or silver to back it up. So, they issued symbolic (fiat) currencies that were backed only by the authority of the government, or they debased the metals content of the coins.

These fiat currencies almost always turned out badly. Instead of cycling up and down in value over time, they tended to go straight down and never come back up. While global monetary history is complex and long, it is highly, highly unusual for a symbolic currency to experience major and sustained deflation at the levels that are the norm with precious metals-backed currencies.

It is this quite understandable but mistaken belief that "a dollar is a dollar” which creates the ironic situation of many millions of people believing that the deflation of the US Great Depression proves the case for deflationary dangers in the current low or no-growth, high unemployment and high debt economic situation. Not at all – what we have instead is the elemental logical fallacy of equating apples with oranges.

Yes, the US experienced powerful monetary and price deflation during the early years of the Great Depression, but that was with a dollar that was backed by gold. In other words, it was a currency that was almost the diametric opposite of today's dollar, which is nothing more than a symbol. With the steward and protector of that symbol's value, the Federal Reserve, being engaged in a multiyear program of quantitative easing that involves creating trillions of new symbols (dollars) out of thin air without restraint.

So, then, the only thing the dollar of 1900 to early 1933 has in common with the post-2008 dollar is the word "dollar". Yet, that has been enough to create this fundamental confusion.

Fallacy Two: Reversing The Historical Lesson

Let’s revisit the sequence of events. The United States was stuck in a powerful deflationary spiral with a gold-backed currency, that seemed unstoppable.

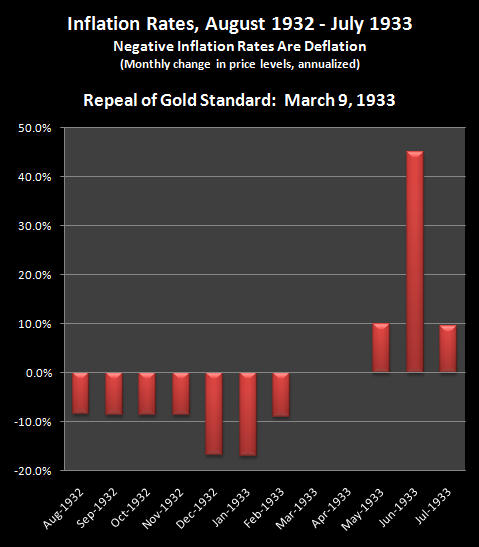

So, the government changed the rules, and replaced the old dollar with a new dollar, whose value was not based on gold. And what happened?

In the depths of depression, and at the height of a deflationary spiral, the government successfully broke the back of deflation within one week. In the midst of deflationary pressures far greater than what we are seeing today, the government not only stopped the deflation, but reversed it with inflation. Indeed, by May of 1933 – only two months after the currency rules were changed – the monthly rate of inflation hit an annualized rate of 10%, and even hit a 40%+ (annualized) monthly rate by June of 1933.

For someone who is concerned about a new US depression leading to unstoppable price or monetary deflation based on what they believe happened in the 1930s, let me suggest they study the above graph carefully, and with a particular focus on March of 1933. And to remember as well the one near-universal lesson from the long and convoluted history of money, a rule which has particularly powerful implications at this time and the years ahead: every time the rules governing a currency lead to a problem that causes too much pain for a government to bear – the government just changes the rules and changes the nature of money.

And the bigger the problem – the bigger the rules change, the more the nature of money itself changes, and the bigger the resulting redistribution of wealth.

So, when we look not at the gold certificates of long ago, but at the dollar we have today, what the Great Depression of the 20th century in the United States historically proves is not the unstoppable power of deflation, but rather the opposite: that a sufficiently determined government can smash deflation at will, virtually instantly, even in the midst of depression, and replace it with inflation.

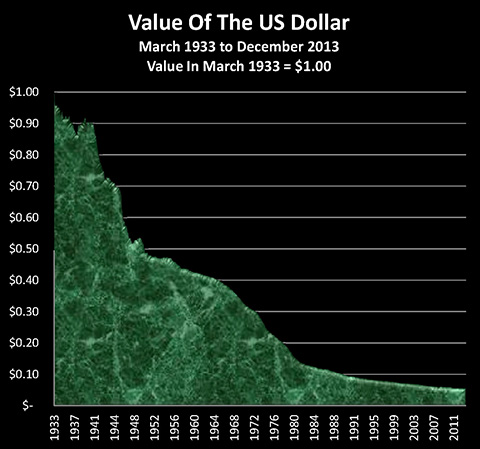

In the process of breaking the back of deflation – the nature of the dollar itself fundamentally changed.

Throughout the 19th century and the first thirty years of the 20th century, the value of the dollar went both up and down, as the (usually) gold-backed currency experienced regular cycles of both inflation and deflation. This cycle was replaced entirely by a new pattern – which could be characterized as down, down, down, as illustrated in the graph below.

(The graph above may look like it starts at 95 cents, but it doesn’t, it starts at $1.00. The fall in the value of the dollar in 1933, once the gold standard was abandoned, was so fast it can’t be seen with a 80 year scale and monthly increments.)

An 80 year old man or woman born in the 19th or 18th centuries would have seen the value of their currency fluctuate both up and down over their lifetimes, and there was a pretty good chance that at age 80, the dollar (or pound) would be worth the same or more than it was when they were born. When the US Government fundamentally changed the nature of money in 1933, it created an entirely different pattern: all down, and no up, so that for an 80 year old person today, a dollar will only buy what 5 cents did at the time they born.

So as we try to determine whether the current danger ahead is inflation or deflation, what is the monetary lesson from the US Great Depression?

The common belief is that the Great Depression demonstrates the awesome power of deflation, which the government can have a great deal of difficulty in fighting, if it can fight it at all. This is an extraordinary misunderstanding, and constitutes the second of our logical and historical fallacies.

What the Great Depression in fact showed was that if you have a tangible asset-backed currency such as gold or silver, and you enter a depression, then as history has demonstrated time and again, you're likely to have a period of substantial deflation.

However, what the events in March of 1933 show us is that even in the midst of a terrific burst of asset deflation and a terrible depression, if you take away the tangible assets that back your currency and you introduce a purely symbolic currency, then the force of inflation that is associated with a purely symbolic currency (as well as the changes in monetary policy that are thereby enabled) can be so powerful that it smashes the deflationary monetary pressures.

Indeed, the historical lesson to take away is that the value of money can turn on a dime when we are using a symbolic currency. Here we have absolute proof that even in the middle of a depression, the government has the power to stop a deflationary spiral at will. We can further see that this deflation-crushing strategy was not a one-time anomaly, but was so successful that it broke the ongoing inflation/deflation historical cycle, and led to a 95% destruction of the value of the dollar over the next 80 years.

What's In A Name?

When we go down to the firmament – the fundamental level of reality for a nation and the globe – a "dollar" is just a name. A name for a variable, that's all it is. In this case, there is a set of policies and rules for the dollar, which are highly variable, even if the name stays the same.

Consider the simple equation 5 + A = B, with the dollar being "A". By itself, "A" is just a name for a variable, it can mean anything. If "A" stands for 10, then "B" is 15. Change what "A" stands for to 10,000, and then "B" is 10,005.

This may sound like numbers-geek talk, and very few people think about money in those terms. Indeed, a great part of the population finds learning about these issues something to be avoided at almost all costs.

But regardless of whether most people understand this or not, it doesn't change the reality that the dollar is just the fixed name for an underlying variable which is anything but fixed. This "technicality" profoundly influences our economy. It can change income, employment and daily standards of living for the nation, and is currently the dominant factor in determining investment performance – at least in the early 21st century.

To better see this, let's track some of the recent changes in the variable behind the name, and how they have transformed the day to day lives of most of the nation and the world. As a starting point (though not "the" starting point), the United States faced major issues with a recession in the early 2000s due to the popping of the tech bubble and the resulting destruction of paper wealth.

The Federal Reserve made the decision not to wait out the recession, but rather to use its powers over the rules and policies that governed the symbol. It set out to counter the negative effects caused by destruction of paper wealth in an asset bubble ("wealth" that incidentally was itself never real) by making the dollar low cost and plentiful. In a move to stimulate the economy, it facilitated the creation of cheap and easy money by the banking system at low interest rates.

The lives of almost every person reading this – in the United States as well as around the world – changed with that decision, whether they were aware of it or not.

That is, while the name "dollar" stayed the same – its underlying nature changed. Moreover, instituting policies that enabled the creation of cheap and easy dollars by the trillions (albeit not directly by the Federal Reserve itself – yet) is what fueled the creation of the real estate asset bubble. For without a plentiful supply of money for all kinds of mortgages at remarkably low interest rates, real estate prices could never have climbed nearly as high as they did, because making mortgage payments would have been unaffordable.

If you made a great deal of money in real estate in the early to mid-2000s, whether through investing or just watching your home equity climb – it happened because the variable behind the name changed. And with that change in what the dollar really was, the economy changed, and so did the net worth of every real estate owner in the nation.

And when this artificially-induced bubble popped, if you or someone you know lost a great deal of money whether by foreclosure, or getting trapped in an underwater home – again, it was that geeky technicality of the rules behind the name changing that had created the bubble of prices inflating, and whose destruction had such a tragic effect on the lives of so many millions of Americans.

A Major Rewriting Of The Rules

In October of 2008, the collapse of the world's financial system was imminent as a result of the implosion of the US subprime mortgage derivatives market, which was driven by the popping of the cheap money-based real estate bubble.

There was a liquidity crisis raging, and a global bank run was in progress. Institutional investors were demanding back the money that they had lent to the major banks, but the banks didn't have the money, and if they were to sell their toxic assets at fire-sale prices to get the money, they would all become insolvent – leading to potential global financial devastation and global depression.

On a national basis, if the dollar were "a dollar" as the general population or many deflationist theorists see it, then it would have been game over, with no way out, because the money simply didn't exist to solve the crisis.

However, the financial order didn't collapse. That is because the person in charge of the rules governing the US dollar happened to thoroughly understand the two deflation myths we've explored thus far, and at will, he used the power of the Central Bank to transform the very nature of the nation's currency.

Benjamin Bernanke was fascinated by the US Great Depression of the 1930s, he'd been a lifelong student of its lessons, and he understood forwards, backwards and sideways that by changing the rules and the nature of money, what had seemed to be unstoppable deflation could be stopped in its tracks, in a matter of weeks. After many years of study, he had become convinced that the Depression had been longer and more severe than it needed to be, the problem being that the government was too timid, and that it should have aggressively changed the rules governing the dollar much sooner than it did.

Faced with a severe global crisis (which had many culpable "fathers", but the fuel for which was created by the Fed's folly in quite deliberately trying to overrule the business cycle with its interventions), Ben Bernanke chose not to walk away from policy changes gone bad – but rather to "double down" with an exponentially greater change in the nature of the dollar. Thus the response of the Federal Reserve to an existential global crisis was to swiftly and aggressively rewrite the rules, by fundamentally transforming the currency – all while keeping the name constant.

Quantitative Easing One created over $800 billion in new money out of the nothingness in a matter of weeks, giving the banks what they needed to meet the liquidity crisis and stay technically solvent.

Understanding that at its core, a symbolic currency is no more than rules and policies, Bernanke reacted to a seemingly impossible crisis by just doing a major rewrite of part of the equation – the rules and policies governing the dollar – and effectively deciding that "Y = $800 billion" instead of its former value of zero. (For those interested, there is a much more detailed description of excess asset reserves, sterilization and how this worked on my website's home page).

This new money was greater than total US physical currency in circulation after 200 years, and in excess of total annual US income tax revenue from just a few years before. The old rules behind the pre-2008 dollar disappeared, being replaced by the new rules, and the $800 billion in freshly created new dollars stopped the bank run in its tracks. None of which was particularly noticed by the population at large, because the variable's name, "the dollar", hadn't changed.

Symbols Creating Reality

However, what did change was the financial world as we knew it.

This is good place to think about two worlds that could exist today – but don't.

1) Think about how different your life and the lives of your loved ones might be if there had been an overt and complete financial collapse in 2008.

2) Think about how different your life and the lives of your loved ones might be if the Federal Reserve hadn't enabled the growth of the real estate bubble and subprime mortgage derivatives market in the first place, if there hadn't been any danger of collapse or crisis in 2008 and 2009, and if the "Great Recession" had never followed.

Either way, let me suggest that employment, income, net worth, retirement, and even food on the table might be working quite differently for many people.

And either way, investment performance would also have been radically different across all major categories including stocks, bonds, precious metals and real estate.

Indeed, when it comes to investment performance across all categories over the last 15 years, there is a very strong case to be made that the two dominant factors have been:

1) Changes in the nature of money in many nations; and

2) The interests of governments and powerful special interest groups, which are what determined which of the possible changes in the nature of money have in fact occurred.

In other words, there is much more variability to what money is and how wealth is redistributed than many realize. The process is far from neutral, and what guides the outcome is monetary gain, power and self-interests.

The tinkering has been nearly continuous since then.

Quantitative Easing One began with bank rescue and then morphed into real estate rescue, transforming real estate investment for the nation.

Quantitative Easing Two attacked the value of the US dollar (thereby changing global trade and stock market performance), and took control of US interest rates and therefore the bond markets – and therefore US solvency when it came to interest payments on the debt. The measures deployed reduced interest earnings by trillions of dollars, negatively impacting tens of millions of savers and investors, as well as pension funds.

Quantitative Easing Three has, among other things, created high bond prices, rising stock market levels, and rising real estate prices. It has contributed to a reduction in precious metals prices, and has enabled a profound redistribution of wealth within society.

Tapers are checking the increases in stocks, and have pushed emerging markets into a tailspin around the world.

Investment performance in any major category around the United States (and much of the world) over the last 15 years cannot be explained without including the profound effects of governments changing the nature of money in a way that serves their own self interests.

Nor can current pricing levels in any major category be explained – without factoring in those effects.

Which raises an essential question: if we can't explain investment markets performance in the past or present without taking into account self-serving governmental interventions that change the rules and nature of money, then how likely are we to make prudent investment decisions for the future, if we ignore those factors?

If the price and yield history of stocks, bonds, precious metals and real estate have all been profoundly influenced by these factors, then how can one make good investment decisions without at least incorporating them as one part of the decision-making process?

The Problem With Deflationary Theory

When it comes to money, my issue with much of deflationary theory is that it is based on myths rather than the two powerful historical realities covered herein. Just as it ignores recent economic history.

Yes, the textbook case for deflation in terms of the supply and value of money occurred in 2008, as it did in 1929. And in both cases the chosen remedy was the same: deflation threatened the currency, and so the rules governing the currency were changed.

When you have a symbolic currency with no outside limitations, the equation can always be rewritten to infinity, as has been shown in a number of nations. And if a nation goes to that extreme, and rewrites the rules and policies to force the creation of a near infinite amount of dollars, this can very quickly translate to hyperinflation and a near zero value for the currency.

Taken to this extreme, this is an absolute power, and there is no struggle. Which means that with a symbolic currency like the US dollar – which only exists by government fiat – inflation can always trump deflation at any time when it comes to the value of money.

Now, the "trick" for the Central Bank – and the corresponding risk for the nation – is the precision involved in not going to the extreme, but rather destroying just enough of the value of the currency to offset deflation while still maintaining control of that process. Too radical a rewriting of the equation, then control to the downside might be lost, and for a combination of external and internal factors, the currency may plunge in value far beyond what was sought (maintaining the value of a symbol is much trickier than destroying that value.)

(Another consideration is that the more powerful the case for monetary deflation with a symbolic currency, and the greater the risks for the nation, then the stronger and riskier the strategies that must be deployed by a Central Bank to fight that deflation, and thus the greater the chances of events spinning out of control, and therefore the greater the damage to the value of the currency. So when someone makes what appears on the surface to be an overwhelming case for deflation - they may actually be making an even stronger case for inflation. Interesting and mind-bending stuff, but I digress...)

To be clear, however, this is not to say that deflation isn't a major danger or that governments can always overcome it. For there is a different and more powerful kind of deflation, the dangers of which are much more solidly-based in both theory and history, and against which governments and markets can be rendered near helpless for decades.

This much more powerful and thus much more dangerous type of deflation consists of changes in the inflation-adjusted value of actual assets, such as securities, property and precious metals. There is a long history of such asset deflation devastating markets in nations for potentially decades at a time, as they try to recover from financial excesses. And this is why as I stated early on, I am an asset deflationist, for I fear that there is a strong chance that asset deflation in purchasing power terms may become an unstoppable force in the coming decade.

In summary, key aspects of current deflationary theory can be characterized as the combination of 1) an absurdity; 2) a misunderstanding; and 3) an oversimplification; all working together to create 4) a serious danger for investors.

The absurdity is the idea that a symbolic currency has some sort of inherent value and power, which a central bank or nation is powerless to fight, creating a situation where the symbol continues to soar in value in a manner that creates or reinforces economic depression.

The misunderstanding, as explored herein, is looking to the history of gold and other asset backed currencies - which are prone to powerful deflations that nations can indeed find impossible to overcome - and assuming that also applies to symbolic currencies, just because the name remains the same.

The oversimplification is mixing the value of money in with the value of assets and thereby saying it must be either deflation or inflation, with those being the only two choices.

The major danger is that because many believe that deflation is highly likely for assets when it comes to value, then because of the misunderstanding and the oversimplification, they believe that they are somehow protected when it comes to the value of their money - and tragically, they could not be more mistaken.

We will explore two further myths about deflation in the second part of this article, as we consider the differences between the value of assets, and the value of money.

To be continued...

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

If you find these "eye-openers" to be interesting and useful, there is an entire free book of them available here, including many that are only in the book. The advantage to the book is that the tutorials can build on each other, so that in combination we can find ways of defending ourselves, and even learn how to position ourselves to benefit from the hidden redistributions of wealth.