Can A Nation $17 Trillion In Debt Afford Higher Interest Rates & Will This Change Our Retirements?

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Below is the 2nd half of this article, and it begins where the 1st half which is carried on other websites left off. If you would prefer to read (or link) the article in single page form, the private one page version for subscribers can be found here:

Shared Interest Rates, Opposite Objectives

Now if interest rates were entirely different for savers and investors than they were for the federal government, this problem with the government needing low interest rates on its extraordinary amount of debt would not be an issue for savers and investors.

Unfortunately, the opposite is true.

Whether explicitly stated or not, almost all interest rates are effectively tied to what is known as the risk free rate, which is the government bond rate. In other words, this federal borrowing rate is the base, most other interest rates are effectively tied to that base, and therefore most interest rates tend to rise and fall with the base federal rate.

So when interest rates on the federal debt climb, interest rates on deposits, money market funds, bonds and mortgage securities all rise as well.

And when interest rates paid by the government on its debt falls, all of these other interest rates usually fall as well.

So there is a sharing of interest rates so to speak, where the interest returns received by investors very directly correlate to the interest rates paid by the government.

Which means that we have a huge conflict of interest between the objectives of savers and the needs of the government.

Impact On Retirement Standard Of Living

There is another crucially important factor which is not just the returns when someone is building wealth by investing over a period of decades, but also the lifestyle that can be afforded once one has actually retired and is drawing down their portfolio to fund their lifestyle.

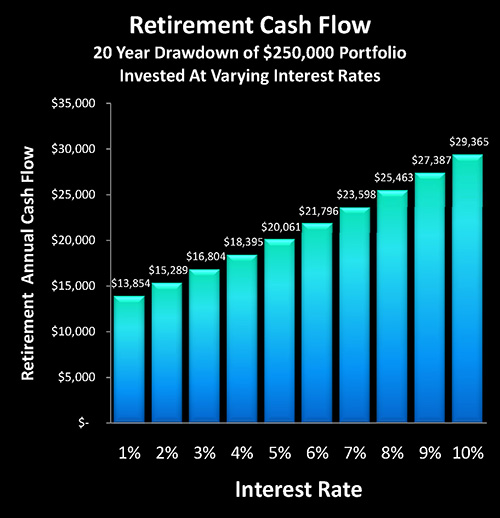

The graph below assumes $250,000 in retirement savings being evenly drawn down over a period of 20 years, with nothing left at the end of the 20 years. Now the higher the interest rate, naturally the more the interest income each year, which allows the principal to be drawn down more slowly. So with higher interest rates, retirees get both higher interest payments and larger average principal balances over time, which can combine to make a surprising amount of the difference.

So if we assume a 7% interest rate, as bonds have often returned over the last 40 years, the $250,000 portfolio would produce $23,598 per year in cash available for spending.

If we were to increase that rate to 10%, the annual standard of living would be almost $30,000 per year.

If on the other hand we were to drop it to 5%, the annual standard of living that could be supported from these investments would fall to $20,061.

Now the heart of the issue with very low interest rates is that if someone holds their money in short-term, high-quality investments that pay a 1% interest rate – then specifically because the federal government has suppressed interest rates to keep them down to a mere 1% – the saver's income is only $13,854 per year for those 20 years.

At a 2% rate it would be $15,289.

While this is little remarked upon, it's the incredibly important heart of the issue.

This drastic reduction in interest rates to serve the needs of a heavily indebted federal government may drop retiree incomes by 30-50% for decades relative to what they would be with longer-term average interest rates.

So tens of millions of retirement investors who are planning on supporting themselves primarily with their investment portfolios and the rewards of their many decades of disciplined savings may see their lifestyles drastically reduced – specifically because the federal debt outstanding is now approximately 17.5 trillion dollars.

It needs to be understood that the extraordinary amount of federal debt outstanding and future retiree lifestyles are tightly linked together.

Who Is Really Paying For The Debt?

Many well-intentioned older people feel very bad indeed about the massive federal debt which they believe we are leaving for our children and grandchildren to repay. And they are correct in that we are leaving tremendous financial challenges for our children and grandchildren, of which this extraordinary level of federal debt is a key component.

There are many more people who don't worry or think about the size of the national debt at all – and who have a strong desire to keep things that way. Yes, they are likely aware that the federal government owes some fantastic, almost surreal amount of money, but it doesn't seem to be affecting their personal daily lives in any way that they can see – so they just choose to ignore it.

Unfortunately, both groups of people – which is the great majority of the population – could not be more mistaken when it comes to the national debt being primarily a problem for the somewhat distant future.

For if we're talking about the value of the federal debt and its repayment in the decades ahead, the debt is actually far more likely to be paid in inflation (as explained here), or through a combination of inflation and artificially-suppressed interest rates (as explained here), than by our children and grandchildren toiling for decades to slowly repay the debt with dollars that have the same value as today's dollar.

Rather than being some far-off burden for our children and grandchildren to bear – the price of the massive amount of federal debt is being paid in the here and the now.

Anyone who has been frustrated by the paltry returns on their savings deposits, money market funds or bond funds is paying the financial price for $17.5 trillion in debt right this minute. Just as they've been paying the price for years now. And they are all too likely to keep paying the price for years and decades to come.

Anyone who has a retirement account is paying a price. Anyone who has or is entitled to a pension is paying the price, because that pension may very well be in financial distress now or in the future because it just can't get the interest earnings needed to meet its obligations.

Conversely – anyone who uses a loan to buy a car now or in the future is likely to benefit from low rates. As will anyone who takes out a mortgage to buy a house.

In some ways, the current extraordinary level of federal debt could be likened to sharing our solar system with a financial black hole. Just because people aren't seeing it every day – doesn't mean it isn't there. Whether seen or not – the massive gravitational pressure dominates everything around it.

And every time someone saves, invests, retires or makes a major purchase – the massive weight of that $17.5 trillion debt pulling interest rates down through the corresponding governmental interventions impacts their life, right that minute.

This "black hole" can be found in other nations around the world as well, for the United States is far from alone when it comes to having huge national debts with a rapidly aging population.

While this massive weight affects every part of society, there is one group that is more affected than any other. That group is the people who are following traditional retirement planning or other long-term investment strategies.

Traditional financial planning doesn't take massive federal debts into account, nor does it take into account the Federal Reserve creating money by the trillions to force interest rates downwards. Instead, investors are supposed to receive market interest rates that will reward them with a compounding of wealth before retirement, and a generous cash flow after retirement.

But if the federal government can't afford substantially higher interest rates – it could be a very, very long time before medium and high interest rates return. And if that is the case – tens of millions of people may never achieve the compounding of wealth they were anticipating for retirement, nor the level of cash flow they were counting on after retirement.

Before any problem can be solved, the necessary first step is to recognize the existence of the problem. Which is, in this case, to understand that a $17.5 trillion federal debt is neither irrelevant to our personal lives, nor is it just a problem for the distant future – but rather it is influencing and changing each of our lives every day right now, and is likely to continue to do so for many years to come, particularly as the debt grows steadily larger.