Is Simple Incompetence The Real Source Of Crises?

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

There are two quite different narratives for explaining the financial crisis of 2008, the resulting Great Recession and the chances for a new crisis. The first narrative revolves around theory and jargon. It's Keynesian versus Austrian economics, it is societal debt levels, it is fractional reserve lending and the velocity of money, and so forth.

There is a much simpler perspective, which is that no matter how exalted the credentials or how elevated the position, at the end of the day we're all human. Which means we're all vulnerable to getting in over our heads and just plain screwing up. And if these mistakes – which effectively result from our not being as good as we think we are – occur at a high enough level, then that has the potential to change economies and investment returns for entire nations, as well as the global financial order, and sometimes for decades to come.

It is this common sense and almost universal understanding that people sometimes get in a complicated mess, then take actions to try to get out of that trouble, but make big, whopping mistakes instead – that may be the most likely source of a potential future crisis.

Was Incompetence The Cause Of The Financial Crisis Of 2008?

Some people will tell you that it was greedy incompetence on the part of Wall Street that created the financial crisis of 2008. Other people will tell you that it was governments intervening in markets, forcing banks to lend to people with poor credit histories who lacked the capacity to repay loans, on the grounds that they had the same right to mortgage lending as their more affluent counterparts.

There is truth within both perspectives, albeit with neither one containing the whole truth.

But there is a third and far simpler explanation. And that is that the financial crisis of 2008 came about as the direct result of Federal Reserve incompetence – in two separate areas.

The first mistake stemmed from the United States being in a recession following the collapse of the tech stock bubble. Now recession following prosperity is of course part of the unending business cycle that has dominated economies over the centuries.

But what made this time different is that the economists running the Federal Reserve believed that their expertise and skills were so great that they could intervene and override the normal business cycle. By making money cheap and interest rates low, they could stimulate the economy and thereby shorten the duration and depth of that otherwise quite normal recession.

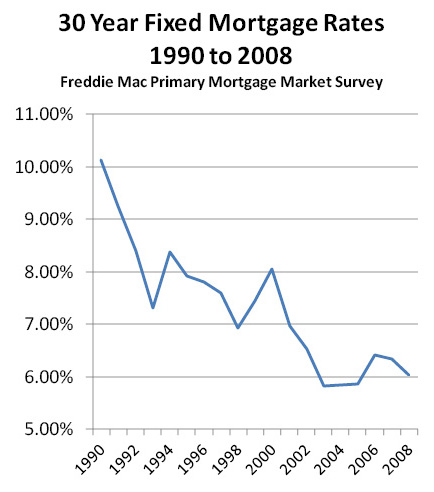

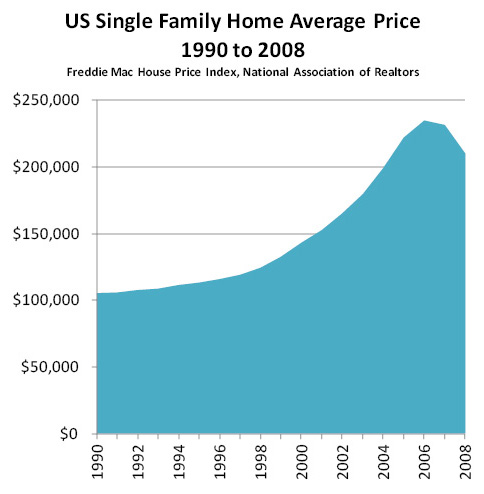

So as shown in the above graph, the Fed drove interest rates to the lowest levels that had been seen in 30 years. And this decrease in interest rates made mortgage payments the lowest they had been in many years, which in turn helped fuel a radical increase in home prices, as seen in the following graph. Lower interest rates were not the only factor – but they provided the essential fuel that enabled everything else.

Simultaneously, the Federal Reserve is the regulator for the US commercial banking system. And under its supervision (or lack thereof), the banking industry created a huge, fantastically complex – and fragile – market in derivative securities, which if stressed could bring down the entire global financial system. With the market in subprime mortgage derivative securities – which was the actual trigger for the financial crisis of 2008 – being only a very small part of the larger derivatives market.

Why the Fed was never held accountable for failing in its duties as banking regulator is a rather interesting question, when we step back and place things in perspective. After all, preventing banking crises was one of the main reasons the Fed was created in the aftermath of the Bank Panic of 1907 – it is core to why the Fed exists at all. And they failed at it, miserably. They completely failed to control risk, with this failure in regulatory oversight nearly bringing the entire system down in 2008.

But rather than being censured or punished, or even replaced altogether, the Federal Reserve was effectively rewarded with vastly increased powers over the US economy and markets.

So we have, 1) a failure in monetary policy which facilitated the creation of an "asset bubble" in the US real estate market. Even as, 2) regulatory incompetence allowed risks in the US and international banking systems to spiral completely out of control, without the Federal Reserve seeming to even notice that it was happening.

And it was when the popping bubble slammed into the newly fragile and high risk banking system – that the global financial order almost melted down.

Now because each of these sources of the financial crisis of 2008 were preventable, then arguably the crisis would never have occurred – if the Federal Reserve had simply been competent in performing its two core duties of acting as monetary steward and banking regulator.

It is interesting that this simple explanation for why the financial crisis of 2008 happened is not more widely acknowledged or discussed. The reason for that may be that it doesn't fit with any particular political or media narrative at the moment, but even more likely it's that relatively few people have any idea of what the Federal Reserve really does.

In any event, the current situation is such that there are no penalties for incompetence. And that being the case, the same basic group of people whose mistakes in judgment arguably were the primary source of the financial crisis of 2008 – are still collectively in power, and aren't feeling any pressure to change their behavior.

Now while this may be advantageous for the economists involved, there can be real problems for a society when it comes to having its chief decision makers being shielded from the consequences of incompetence.

And this is particularly the case given the extremely complex and fragile place in which the global financial system currently finds itself.

The Complex & Dangerous Challenges Ahead

Since 2008, US interest rates and market performance have arguably been dominated by the very active interventions of the Federal Reserve. Interest rates have been forced to historic lows, and the Fed has used extraordinary amounts of monetary creation to reach this objective. As further explored here, these very low interest rates have in fact been a key component of why bond and stock market prices have reached record levels, even while the underlying economy continues sputter, with the negative GDP growth in the first quarter of 2015 being only the latest example.

On a global basis, we are also in an interlinked and fragile financial situation, where central banks have been competing with varying levels of quantitative easing in order to lower the value of their currencies and give their national economies competitive advantages.

And perhaps most importantly of all, and enabling all of this – is that the world's largest and most sophisticated investors, the institutional investors, have been "retrained" to view the dominant source of market movements as being central banking actions.

Now the Federal Reserve has been talking about their desire to change this situation. They say they want to at least slightly increase interest rates. And they would like to gradually move the markets back towards a place where it is fundamentals that drive price movements instead of interpretations of key sentences in central banking statements.

There are myriad complications, however. For one, no one's ever done this before – this is new economic theory that is being tested as we go.

How exactly does one handle that transition from institutional investors basing their market judgments on central bank policies to making their judgments based on the economic fundamentals – without triggering a collapse in asset prices for stocks and bonds? How does one get off "the tiger" without being eaten (as explored here)? Now those are difficult and tricky questions.

In this tightly interlinked world of ours, how much instability is introduced if the Federal Reserve gets out of synch with the rest of the world by increasing interest rates – thereby making the US dollar far more attractive – at the same time that the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan and others are all using record degrees of quantitative easing to drive down their own currencies? Now that is another very good question.

What will happen to US unemployment if as a result of a surging dollar, American workers are suddenly at a major disadvantage relative to workers in Japan and Europe? What will happen to economic growth if US companies lose market share for both exports and imports simultaneously as a result of this stronger dollar? The answer to those two questions could change everything.

What happens to stock market values if the near zero interest rate source of market support is withdrawn simultaneously with investors determining that they can no longer rely on the Federal Reserve for support, at the same time that US companies are losing market share both domestically and on a global basis? Now there is a major dilemma!

And here is another compelling question: is there the potential for something to go wrong in that process?

The Problem With Vast Powers

Central banks such as the Federal Reserve, working together with national governments, have great powers indeed. They can create money at will on a multi-trillion dollar scale. If the laws and regulations limit them, the laws and regulations can be changed along with the very nature of money itself.

So what may look impossible if we look at money as being a limited resource, or if we look at something working within the current legal framework, can indeed be overridden at will. As we've seen around the globe ever since 2008.

However, if we move away from theory and grand powers to a much more fundamental perspective – which is that of people being well, just people – then these extraordinary powers are not necessarily a solution to the problems, but can instead become the problem itself.

Sometimes people who have extraordinary powers come to have a very high opinion of their own intelligence and their ability to effectively use those powers. They can sometimes become overly confident. And if in their hubris, that same group of people whose incompetence arguably caused the last crisis, attempt to use these grand powers to do something much more complex and difficult than what they had failed at the last time – it's just possible that the outcome may not be at all what they anticipate.

Indeed, the outcome for us all may quite different from what most expect.

We currently face a far more complex set of circumstances than we did in 2007 and 2008. And perhaps an important question to ask ourselves should be: if the central banks just plain weren't competent enough to handle the last set of problems, how certain can we be that they will be able to handle our current and future challenges?

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

If you find these "eye-openers" to be interesting and useful, there is an entire free book of them available here, including many that are only in the book. The advantage to the book is that the tutorials can build on each other, so that in combination we can find ways of defending ourselves, and even learn how to position ourselves to benefit from the hidden redistributions of wealth.