Did An Obscure IMF Document Start A Global Bail-In Revolution?

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

When revolutions start, it's not uncommon for almost nobody to notice. It may take years or even decades before historians can look back, point a finger and say "that's where it really began."

An obscure International Monetary Fund "Staff Discussion Note" may have already started a "Bail-In" financial revolution that could transform the global investment world.

In this quite remarkable document, the staff discusses a world where risks to the global financial system have not gone away – but are worse than ever. As candidly discussed, the "SIFI" (systemically important financial institution) problem has not been improving, but instead has been getting worse than ever – and there doesn't appear to be any solution under existing contract law and bankruptcy law.

More risk than ever is concentrated in fewer financial institutions, while there is no way under existing law to unwind a failure of one of these institutions without risking triggering global financial chaos. Moreover, there is a deadly feedback loop between these "too-big-to-fail" institutions and sovereign governments. That is, as the IMF staff discusses, the bailing out of these massive institutions can bankrupt sovereign governments, and sovereign governments going bankrupt can wipe out the "too-big-to-fail" institutions.

So the IMF staff has come up with an audacious plan for how the globe can emerge from this seemingly impossible situation. The key word is "insurance".

The proposal is to take selected classes of investments, and retroactively decide that these assets aren't really assets at all. Indeed, the owners of these assets have – without realizing they've done it – agreed to provide insurance for the global financial system. So if a major crisis arises, the global financial system merely goes to these unknowing "insurance" providers and helps itself to their assets effectively, and the crisis is dealt with. It's a miracle solution!

Now there is the issue that some investors might actually object to this taking of their investment assets for the greater good of society. Which is exactly why the IMF staff recommends that this be done by way of statutory law, in a manner that overrides contract law – and is involuntary, with no investor permission needed. It would also be retroactive as needed, thus applying to people who already own these classes of investments.

After the bail-ins of the Cypriot banks and the Polish retirement system, the development of bail-in procedures is spreading rapidly around the world, including the EU, Canada and the United States. What is fascinating and troubling - though perhaps not surprising - is how global politicians are in practice completely changing the "bail-in" concept, setting aside the IMF-proposed changes that could have forced genuine banking reforms and potentially increased global financial stability, and instead are creating a broader threat to investors.

Moody's Investors Service has already lowered the credit ratings of Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase and Bank of New York Mellon in anticipation of possible future bail-ins. Moody's accompanying statement explained: "Rather than relying on public funds to bail out one of these institutions, we expect that bank holding company creditors will be bailed-in and thereby shoulder much of the burden to help recapitalize a failing bank."

A World At Risk

The IMF Staff Discussion Note is titled, "From Bail-Out To Bail-In: Mandatory Debt Restructuring Of Systemic Financial Institutions". Originally released in 2012, it could be viewed as a source document for the global movement to bail-ins. The note is available on the International Monetary Fund website, and a link for downloading the PDF is below:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2012/sdn1203.pdf

(The original discussion is well worth reading, and this analysis refers to particular document page numbers within it. Please note, as is often the case with PDF documents, that the page number in the actual document (which is what you will see if you print it out) is one off from the electronic PDF page number.)

One of the main questions explored in the document is just why the IMF believes that the world needs these major changes in the laws and how investments are treated.

While positive headlines abound in the media about rising stock markets and improving conditions, as it turns out, the International Monetary Fund staff sees a quite different picture. What they see are serious ongoing risks to the global financial order that are being caused by the major financial institutions around the world – which they refer to as SIFIs, otherwise known as "too-big-to-fail" institutions.

As covered on document page 4 (PDF page 5), there are three different ways in which the failure of even a single SIFI can imperil the entire global financial order.

The first major risk is "direct counterparty risk", with the SIFIs having an extraordinarily complex web of hundreds of trillions of dollars of interlocking commitments and contracts between themselves. The failure of a single SIFI could trigger a chain reaction of losses that would spread like dominoes, knocking down one SIFI after another – as well as other banks and investors around the world.

The second major risk is one of "liquidity". Since SIFIs rely heavily on borrowing, if the sources of their funds flee in the event of trouble, this would leave the SIFIs potentially insolvent unless they could quickly sell assets to cash out departing lenders, which would rapidly drive down prices, and with everyone selling assets together this could create a global "fire sale" on investments that's enough to crash the world's financial system in a matter of days.

The third major risk is one of "contagion", where the failure – or even looming failure – of one major institution introduces a psychology of panic into the marketplaces, which by itself is more enough to bring down the global financial order. After all, perception can and does create reality when it comes to financial markets.

Now all of these risks received a great deal of attention after the global banking system nearly went under in 2008, and in theory they were supposed to have been taken care of by restricting the ability of the SIFIs to take risks, and also by reducing the percentage of the world's financial assets that are held by the SIFIs.

However, as covered at the bottom of page 4 (PDF page 5) – this hasn't been working out in practice.

To the contrary, there has been an even greater consolidation of assets into these "too-big-to-fail" banks and financial institutions than there ever was before the crisis started. As a result, this has created "unsustainable public finances", where the extraordinary cost of conventional bail-outs potentially threatens the solvency of the nations themselves. And such a sovereign insolvency could in turn trigger insolvency for the SIFIs. So again we have a toxic feedback loop between the SIFIs and the nations that must bail them out in the attempt to avert global financial collapse.

The IMF also identifies the related problem of a "shadow banking system" which also creates systemic risk, but is not subject to the same regulations as the formal banking system.

As discussed on page 8 of the document (PDF page 9), there are two other major problems with the global financial system that feed into these three major risks, making them far more dangerous.

One of them is that because these major financial institutions are generally exposed to a huge amount of risk in their derivatives holdings – which on a global basis dwarf the equity that they have – these derivatives in an insolvency situation could lead to a "disorderly unwinding" which could disrupt the financial markets. In other words, it could lead to a global financial meltdown – although the IMF staff uses a little more carefully chosen vocabulary.

The other core problem, as analyzed by the IMF staff, is that general corporate insolvency proceedings do not provide sufficient tools to manage the risks to financial stability when it comes to a SIFI failing. Which means that under existing law, there simply isn't the capability to manage this – except by bringing in massive amounts of public funds from already financially stressed sovereign states, which then risk triggering their own insolvencies, which then also risk triggering the insolvencies of other SIFIs in this toxic feedback loop.

Plainly put, the existing laws can't handle the problems that have been created by this intertwined world of "too-big-to-fail" institutions that continue to take massive financial risks for private gain, seemingly beyond the control of the sovereign nations, even as the sovereign nations dealing with their own financial problems increasingly lack the credible financial resources to massively bail-out these institutions without risking their own solvency. So the bail-outs are unaffordable, but yet a failure to bail-out would lead to swift global financial chaos.

The Insurance Loophole

For an outside but rational investor, the solution might seem to be obvious. We didn't have this problem before the SIFIs – so get rid of these "too-big-to-fail" financial institutions. Break them up. Restrict their ability to take risks if the public is necessary as a backstop for them to take risks. Unlimited and unregulated risks are fine, but only those which their private investors / owners can actually afford to take. So that in the event of bad decisions leading to failure, the private investors may be wiped out, but no public backstop is needed.

And in doing so, the need for the public to bail-out these institutions would end, as would the toxic feedback loop between the SIFIs and the effectively bankrupt sovereign nations.

Now the IMF staff is aware of this obvious solution, but is very careful not to touch upon it, other than perhaps to implicitly say it just hasn't been working.

That is because the core of the problem is political. The SIFIs are simply too politically powerful for them to be broken up by the politicians of the sovereign developed nations. It's simply not politically practical for the governments to change the behavior of these institutions – even though they place the stability of the entire global financial system at risk on a daily basis.

So when considered from a practical political perspective, another solution needs to be found.

The alternative solution that the IMF document proposes is to use "bail-ins" instead of "bail-outs". My recent article titled, "Bail-ins & Taking Private Wealth", explains in further detail the concept of bail-ins, and how they're currently being used in the real world.

http://danielamerman.com/articles/2013/BailInC.html

One way of looking at a bail-in is that it is the opposite of a bail-out. In the case of a bail-out, when there's an issue with a bank (or government, or government retirement system) not having enough assets available to meet the claims against it, funds are brought in from the general public, supposedly to serve the needs of the general public.

With a bail-in, there is no bankruptcy, but assets are taken from selected investor classes, thereby reducing the claims against the corporation. Solvency is therefore achieved and the needs of the general public are met, but without the general public having to actually pay for it.

Now while the IMF document uses the term "bail-ins", they also offer a quite different way of explaining the process, as shown on page 7 (PDF page 8). As stated, "the bail-in capital could be seen as a form of insurance (provided by creditors) against bank insolvency".

Now if we think through this approach – this way of finding completely new solutions for a system that otherwise lacks solutions, the implications are global, and they are extraordinary.

The way it works is that in the event of a potential financial meltdown, the government – or international organization – identifies particular investment types and classes of investors. These investors hold assets, and in some cases these assets are the liabilities (such as bonds) of the institution that is in trouble.

The government effectively says to these investors, "you may think that you own an asset, but what you've really done is you have underwritten an insurance policy. And if this institution in which you've invested your assets should run into financial difficulty, you have in fact pledged your assets to prevent the insolvency of the corporation, for the greater good of the global financial order".

Now the owner of the investment asset had no idea when they made the investment that they were doing this. They've never received an insurance premium for taking this risk. But nonetheless, a category of investment assets are retroactively declared to be insurance, and they can effectively absorb all the losses and keep the SIFI – or the government, or the public retirement system – solvent for the benefit of all.

Using Statutory Law To Override Contract Law

Now because the investors – whose assets are essentially funding the insurance that preserves the major financial institutions – didn't actually realize that what they were doing was pledging their assets to guarantee the payment on insurance claims, there's a case to be made that this could be a bit sticky from a contract law perspective. Given that this didn't appear anywhere in the prospectus.

Which brings us back to our previous discussion from page 8. One of the reasons for bail-ins in the first place is that using the current laws as written for traditional bankruptcy proceedings simply doesn't work to try to unwind one of these "too-big-to-fail" banks. Per the IMF staff it can't be done, as there's simply too much global risk and damage.

So there are three key paragraphs on page 12 (PDF page 13) that address this. The first one is that "there are compelling arguments in favor of an approach that minimizes the role of the courts". Keep those judges out of it in other words, as they might not do what they're supposed to do. Indeed, the IMF explicitly recommends not allowing the judiciary the ability to reverse this resolution, although it could be allowed to award damages in some instances.

Instead, it is more appropriate for the "decisions to be taken by the banking authorities". In other words, the very same regulators who failed to properly regulate the banks and allowed the disastrous situation to be created in the first place are the best possible experts resolve the crisis.

There's also the problem of getting creditor approval that might be required in a bankruptcy. The IMF document addresses this as well, stating that "the need for quick and decisive action in the interest of financial stability pleads against incorporating a procedure for creditor approval". Getting creditor approval can be a very messy part when going through a bankruptcy proceeding – therefore it's simply eliminated with the bail-in structure.

Perhaps most important of all is the bottom paragraph on page 12, which states that "bail-ins should be applied to existing debt as well as debt issued after the bail-in power is enacted".

In other words, this is retroactive when it comes to investment decisions. In theory, the IMF proposals are based on nations enacting bail-in legislation in advance, so investors are warned, and the yields on securities that are subject to bail-in should rise proportionately as the market evaluates the insurance premium that it should be receiving for providing this protection to other investors.

However, in the real world, as the IMF acknowledges, when you need the assets – you need the assets. So the government takes them, regardless of whether the investor had any idea at the time they made the investment that they would be subject to becoming "insurance" and having their assets effectively taken and converted into potentially worthless equity.

The Source Of The "Free" Insurance

Now let's more closely examine the potential sources for this miracle cure for financial crises, which allows for rescues without limit, and which doesn't require raising taxes or increasing the deficit.

We'll do so by considering something most people rarely do, which is what savings really are.

When we make a deposit at a bank, we are taking our assets and providing them to the bank for its use.

What most of us usually don't think about is that the moment that deposit occurs, a new liability is created – for the bank. It's a liability simply because they will have to pay us back. So it is their promise to pay us back – their liability – that is our asset, that is our savings, and is our source of security.

And traditionally – absent a bail-out – if the bank does a bad job of it and the investment assets become worth less than the liabilities, then the financial institution becomes insolvent, everyone there loses their jobs, the shareholder's stock investments get wiped out, and depositors and other lenders (or the bank deposit insurance fund) take a hit.

Now with bail-ins, the drastic shift in the traditional perspective is that it is our assets that are recognized as being the threat to the too-big-to-fail banks.

With the old bail-out paradigm, bankruptcies are triggered by assets falling in value. With the new bail-in paradigm, it's not falling asset prices that cause bankruptcies – but instead it is having too many liabilities that causes the bankruptcy.

And because of the importance of these financial institutions and their extremely powerful political connections, what has been figured out is that governments can deal with the threat of insolvent banks by dealing with the threat posed by their liabilities.

Once we accept that the liabilities which threaten the global financial order are the same thing as our assets and our deposits – then we need to accept that with the new bail-in paradigm, in the event of a major financial crisis things may not work at all like they used to, and it could be our savings that pay the price.

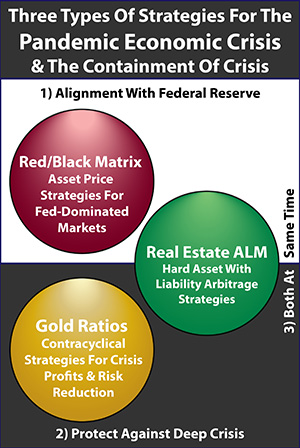

Rethinking Assets & Safety

The global movement towards bail-ins in dealing with financial crisis obviously creates a fundamental conflict between the needs of society in this case, versus decades of almost unquestioned assumptions among the financial community and individual investors.

It also creates a sharp bifurcation between two entirely different categories of assets.

The first category of assets has value in a fundamental sense, but no fixed value. A financial asset like a stock which represents an ownership interest in a corporation is one example.

Tangible assets are another example, where the asset is something we can physically reach out and touch, such as real estate or precious metals.

What they all have in common is that you own an actual asset. What they also all have in common is that you never know for sure what you can sell them for in the future – as the price of the asset is likely to bounce up and down with the markets.

The second category of assets is when somebody – often a large financial corporation – owes you money. This could be a deposit, or a bond, or an annuity. It is the promise to pay you that is the source of value to your asset.

Now we might on a common sense basis say that we would rather own an asset that's real, instead of relying on the promise of someone else to pay us back.

But with the traditional financial theory of recent decades, what have been considered the safest of all assets for investors have been assets that are really the liabilities of other organizations, the promises to pay us back. And the reason they're deemed to be so particularly safe is that this promise to pay us back has a fixed value (in nominal terms at least, before inflation).

We know the principal amount that will be paid to us. And in some cases, we know the interest that will be paid to us. And this is intended to bring a certain amount of security to us when it comes to covering calculated monthly expenses like housing, or food or transportation in retirement.

However there's an inherent assumption with that, which is that it is highly reliable – indeed practically guaranteed – that we will be repaid.

That is, assuming that we're investing our money conservatively, perhaps through a highly rated financial organization, or in using a large mutual fund to achieve a high degree of diversification through our 401(k) accounts – if done properly, it is supposed to be near certain that we're going to get our money back.

But when it comes to preserving the financial order, what has been recognized by the governments of the world is that the cheapest form of financial rescue is quite simply to wipe out the value of some of the liabilities – without going through bankruptcy.

So what this tells us is that when we provide our money to major financial corporations, we may now be inadvertently entering into a direct and powerful conflict of interest, where in the event of crisis the government has very strong financial incentives to rewrite the rules so that we don't get repaid all of our money.

On the other hand, when we purchase a straight-up asset such as real estate, precious metals or stocks – which have fundamental value, and more importantly are not the liability of anyone else– then there is no conflict of interest.

Therein lies the stark contrast between the two categories of assets that may turn out to be the most crucial consideration of all in the years ahead – choosing assets where it is not in the direct financial interests of governments and corporations to reduce the value of our investments in the event of crisis.

Unfortunately, these potentially deep conflicts of interest between governments and investors are not even considered by most conventional investment strategies. To a large extent traditional financial theory is instead basically moving along on inertia and autopilot at this point. We have unquestioned assumptions with regard to the safety and security of the overall financial order that have been driving traditional financial planning for many decades.

Meanwhile, the governments tell us through words and press releases that everything is fine, but when it comes to actions, procedures enabling bail-ins are spreading rapidly around the world because the governments know that's not truly the case.

And what may seem like this minor technical distinction between "real assets" and "liability-based assets" could be one of the major determinants of investment security – or insecurity – for many tens of millions of investors around the world.