Fed Forced To Use Negative Liabilities

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetCan a loss be declared to be a gain? Is it legal to declare that the worse the losses - the greater the assets that are created from the losses?

For most of us, we would be charged with fraud if we attempted to do this. However, if the entity is the Federal Reserve - then the answer is yes. (It helps the books to make the rules that govern the books.)

The Federal Reserve is in a new kind of trouble, and for the first time it is now resorting to what could be called a hall of smoke and mirrors, where reality itself is inverted, and losses can be turned into supposed "assets" that are expressed in the form of literal negative liabilities on the balance sheet. Because this reality is the basis for our money and our financial system, that means we are all traveling down this new rabbit hole together.

Most people think they know what money is. Most of them are wrong - or at least they are for what the U.S. dollar actually is in 2022. As we will explore in this analysis, it is only when we see the new and experimental nature of the U.S. dollar, that we understand the source for these bizarre negative liabilities - which the technical solvency of the Federal Reserve, and therefore the solvency of the U.S. government are now becoming dependent upon.

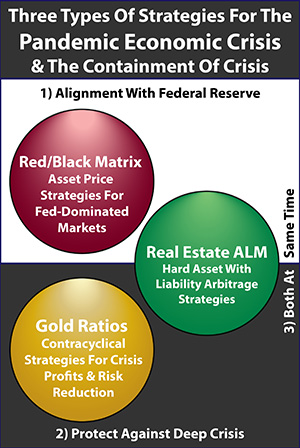

This analysis is part of a series of related analyses, which support a book that is in the process of being written. Some key chapters from the book and an overview of the series are linked here.

Negative Liabilities

A negative liability is a literal negative number that is entered on the liability side of a balance sheet. Let's say that an entity has $1 billion in assets, and $900 million in debts (liabilities). We take the assets, we subtract the liabilities, and we are left with an equity or net worth of $100 million.

Now, let's say we take a $100 million loss - and it is a real loss, a cash loss, and not just a bookkeeping entry. This leaves us with a choice. We can sell $100 million in assets to get the $100 million in cash to cover the loss - and that will leave us with $900 million in assets, $900 million in liabilities, and $0 in equity.

Alternatively, if we don't want to sell assets - perhaps to avoid taking a loss on the sale - we can borrow another $100 million, and use that money to cover the $100 million cash loss. We end up with $1 billion in assets, $1 billion in liabilities, and $0 in equity.

Those are the basic options for conventional accounting. However, if we get to create our own accounting rules - as the Fed effectively does - then we have an alternative. We can declare that our loss is actually a gain, a deferred asset (more below), and we can enter a negative liability on our balance sheet to reflect this.

So, we borrow another $100 million in cash to cover the cash loss, and we have $1 billion in assets and $1 billion in debts. Before calculating equity, however, we subtract the new $100 million negative liability, a literal negative number, that now appears on our liability side. We are now back to $1 billion in assets, $900 million in liabilities and $100 million in equity. Oh, the $100 million in new borrowings still exist, we had to borrow the money or we would be insolvent on a cash basis - but we can no longer see that new debt in the sum of our liabilities, because it has been canceled out by the new negative $100 million liability that also appears

Oh boy, it's fun to get to make the rules, isn't it? But wait - it gets better.

Let's say we lose another $100 million the next year (or the next month). We still don't want to sell assets, so we borrow another $100 million to cover the cash loss. In ordinary circumstances, we would now have $1 billion in assets, and $1.1 billion in debts, so we would be insolvent by $100 million. Unless we make the rules.

If we make the rules, then we declare that the loss of another $100 million in cash has created yet another $100 million in deferred gains. We express that by increasing our negative liabilities to $200 million. We start with $1.1 billion in liabilities, we add the negative number of $200 million, which means the sum of our liabilities is now $900 million, and when compared to $1 billion in assets, we still have $100 million in equity. When we compare the sum of the assets to the sum of the liabilities, the very basics of accounting, then nothing has changed. We never took the $200 million in losses, or took on another $200 million in debt, because the new debt has been cancelled out by the negative liabilities. The $200 million in losses AND (crucially) the $200 million in new debt are now invisible.

Sound a bit strange? Then don't look too closely at the dollars in your wallet, or the dollars in your bank account, because their value is based on negative liabilities as of October of 2022. As is the stability of the U.S. markets, the solvency of the U.S. government, and the reserve status of the U.S. dollar.

The Liability For Earnings Remittances Due To The U.S. Treasury

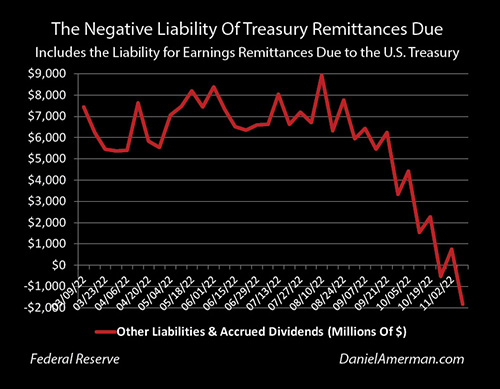

This negative liability is not some wild theory, but a matter of public record. Every Thursday, the Federal Reserve releases its H.4.1 statistical release which includes the consolidated balance sheets for all the Federal Reserve banks from the previous day. As can be seen in Table 5, the liability line item "Other liabilities and accrued dividends" was entered as a negative $521 million for the week ending October 26th, and a negative $1.8 billion for the week ending November 9th, 2022.

This unprecedented movement into negative liabilities is captured in the graph above. What had been almost $9 billion in ordinary liabilities as of August 10th, began a steep descent until it reached a literal negative liability of $1.8 billion three months later.

This previously obscure line item of the consolidated balance sheet of the Federal Reserve Banks is mainly composed of "the Liability for Earnings Remittances Due to the U.S. Treasury". In ordinary times, the Federal Reserve runs a profit. The Fed makes remittances of those earnings to the U.S. Treasury on a semiannual basis. When the earnings have occurred, but have not yet been paid to the government, then the Federal Reserve treats the obligation to pay money in the future as a liability today. That is very ordinary accounting, and a fairly minor line item entry, that the average saver or investor can usually completely ignore.

What is new and unprecedented is that the Federal Reserve is now running at a loss and not a profit (more below). It is borrowing the money to cover those losses. But, it is not reporting the losses, and it is removing the additional debts from the sum of its liabilities.

What the Federal Reserve is saying is that every dollar of losses that it takes today is a reduction in its future liability to pay profits to the Treasury. Losses today then become what the Fed refers to as a "deferred asset". Because this deferred asset is a reduction in future liabilities, it is expressed as a negative number on the liability side of the balance sheet, exactly canceling out the new debt that was taken on to cover the cash losses.

Again, this is bizarre smoke and mirrors stuff. In general terms, putting out financial statements that claim cash losses are really assets while hiding new debts is a good way to get to know the federal prison system from the inside. However, in this case, the rules that govern the Fed's books are what the Fed says they are.

Money Is Debt

So, what is the source of the losses? The answer is easy - and yet, it will be almost impossible to see for much of the population, because it contradicts well-known "facts" that are actually myths.

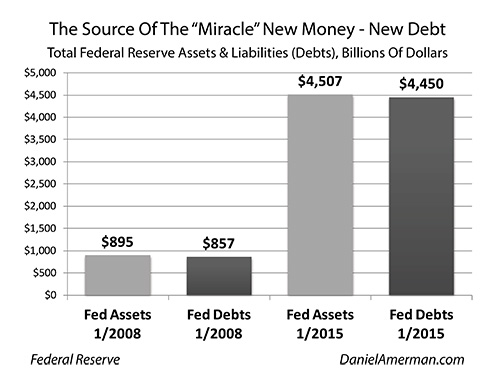

As shown above, and as described in my book "The Stealthy Raid On Our Bank Accounts" (free first chapter link here), the Fed rescued Wall Street and funded quantitative easing - transforming the markets - by borrowing the money. When the Federal Reserve increased its assets by $3.6 trillion between 2008 and 2015, it didn't "print" the money, but rather it borrowed the $3.6 trillion. It still (effectively) owes that money. And it has to make interest payments today on that money borrowed long ago.

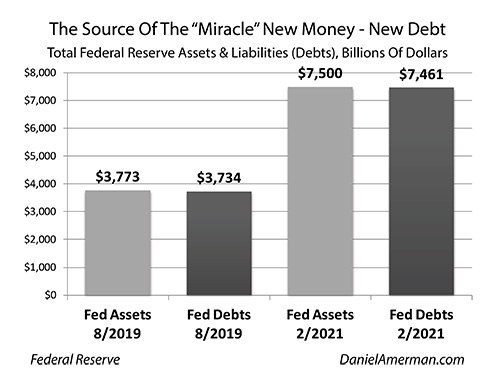

When the Federal Reserve funded the stimulus checks and the fantastic run-up in the national debt during the pandemic shutdowns, it did not "print" the money, but it borrowed the money. Those debts are still outstanding, interest payments have to be made, and interest rates are rising.

Paying For The Easy Money Of The Past - Indefinitely

We have seen what could be termed a double myth of easy money, which is being refuted on both sides. One myth was that of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), and the belief that the government could run up the debt and spend without limits. This is very appealing from a political perspective for the large portion of the population that has no understanding of economics - but it was always simple-minded, as it left out the accumulation of debt, and interest payments on that accumulated debt.

With MMT the debt never gets paid down, and it just goes higher and higher, reaching ever more fantastic levels. The other (lame-brained) assumption underlying MMT is that interest rates could be kept near zero indefinitely. This completely ignored financial history as well as the possibility of inflation returning.

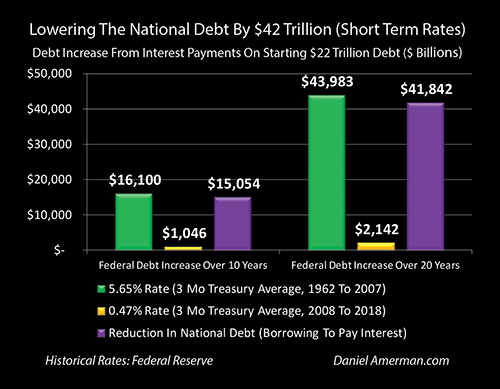

The problem, as I've been explaining for more than ten years, and as is illustrated in the graph from Chapter 18 (link here) in 2018, is that high levels of national debt cannot handle a major increase in interest rates, including a return to historical averages. This is because the government borrows the money to make the interest payments, meaning it is paying interest on interest, and an increase in rates sets off a compound interest problem, that rapidly increases deficits and a compounding of the national debt beyond control. The difference in 2022 from the graph above is the national debt potentially increasing by over $60 trillion from borrowing the money to make interest payments on interest payments, due to the 50% increase in the national debt in four years.

This is now being referred to as a "Doom Loop" as it begins in practice, but it has always been there. Every irresponsible step in sharply increasing the national debt has always had this financial suicide loop built into it, it was just being ignored by an irresponsible federal government, an enabling financial media, and a very short-term thinking Wall Street.

There is another (irresponsible) level to the Doom Loop. The very low interest rates for the national debt were created by the Federal Reserve borrowing the money to force interest rates down to unnaturally low levels - which then simultaneously lowered the Fed's own borrowing costs. As originally designed by Mr. Bernanke, this was a very clever step indeed, unless... unless interest rates rise too much while the Fed has its own high borrowing levels, and then look out. The Federal Reserve has just now "crossed the Rubicon", in terms of borrowing the money to make interest payments, which it hides by using a negative liability.

So, we now have a double potential Doom Loop going, with the government and the Federal Reserve each separately borrowing to make their own interest payments, that may just be getting started. The full relationship with debts, interest rates and inflation goes far beyond what will be covered in this introductory analysis, but anyone who is feeling complacent about the Fed being in control may be in for the surprise of their (financial) life.

Money Printer Goes Brrrrrrrrr...

The other myth is a very popular one - and it can even be a fun one too. Every time the Fed spends another hundred billion or trillion dollars, then those in the know just say "Money printer goes Brrrrrrrr....!". There are some great memes that go with it, and I particularly enjoy the animated GIF that has Fed Chairman Powell literally cranking on a printer that is sending the dollars flying. It is fun and well done.

But, it just isn't true, and believing that it is true is not a harmless error, but could be called a dangerous mistake.

I write this knowing that confirmation bias rules for most people, and that cognitive dissonance - however factual - is going to be unpopular. So, my apologies, as I don't mean to offend, but there are times when the truth needs to be spoken. This isn't a matter of opinion or differing views, it really is just the facts as can readily be seen on the consolidated balance sheet of the Federal Reserve Banks every week.

The Federal Reserve did not print the money for QE to buy government bonds from 2010 to 2014. The Fed borrowed the money to fund quantitative easing. While the money was spent by the government long ago, most of those debts are still outstanding. It isn't just that the government is still paying interest on its debts. The Fed is also still paying interest on most of the money it borrowed, on what is usually a daily basis with overnight borrowings, and those interest payments have been rising fast.

The Fed did not print the money for the pandemic stimulus checks. It borrowed the money, by the trillions of dollars. That money too has all been spent by the government. However, the Federal Reserve still owes all the money that it borrowed, and it has to continue to make what are usually daily interest payments on that debt, even as it sending those interest rates higher and higher in the attempt to combat inflation.

Each time that the Federal Reserve spends the money to fund the national debt - it creates what is effectively a one-way ratcheting mechanism on the cumulative amount of money that it has borrowed to fund that spending. Each time the Fed raises interest rates, it increases the cash that it pays out. A similar process is happening with the government debts - a one way ratcheting process with steadily more fantastic amounts of debt that are subject to interest rate risk.

The Federal Reserve used the trillions of dollars it borrowed to fund vast amounts of long-term government debt and mortgage-backed securities at very low interest rates, in what it thought was an act of economic genius. That money is long gone, and the interest payments made to the Fed are quite low (by design). However, the rising interest payments made by the Fed still have to be paid daily, and they have now reached the point where the money is going out the door faster than it is coming in, which has the Fed relying on some quite unusual accounting tactics. This would not typically be considered an act of economic genius.

So, there are layers upon layers of debts owned and debts owed. This layering of debts is the subject of Chapter Nine of "The Stealthy Raid On Our Bank Accounts" - and it is critical information. People believe money and things like Social Security are based on assets. There are no real assets - the gold-backed dollar is long gone. Instead, all the "assets" are debts, usually from entities that are already fantastically in debt, with no means of repaying their debts or even making interest payments on their existing debts - other than by taking on new debts.

And, while it was outside of the modeling assumptions used by the Federal Reserve - if the new debts have to be taken out at much higher interest rates than assumed, for a long enough period of time - then the financial viability of the entire system is at risk, including the value of the dollar (and euro), the reserve status of the dollar, the collective real value of the stock and bond markets, and the financial viability of Social Security and the pension system. This risk is greatly exacerbated by persistent inflation.

Reality is complex.

Ignoring the complexity, particularly if it conflicts with confirmation bias, is the natural human response to being confronted with new information that induces cognitive dissonance. That is a different form of reality.

However, when the complexity is in the process of failing, it also pretty much guarantees a blindside at some point, as the mainstream who ignore the complexity sees a failure in most aspects of what they believed would be their financial futures and their future standards of living. Hopefully, this analysis has been helpful in seeing what is actually happening, even as the source of financial stability in the U.S. resorts to labeling losses as assets, and bases its books on literally subtracting losses incurred from debts owed.