Chapter 18: The New Threat To Housing & Stocks From Government Deficits

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA, MBA, BSBA

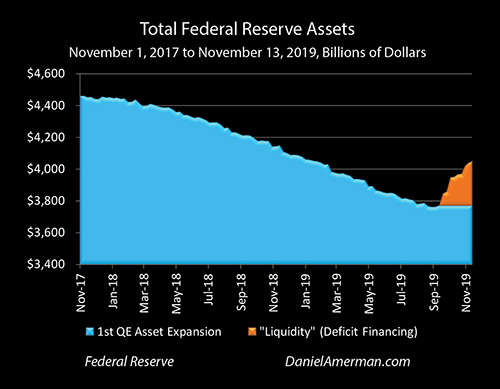

TweetA new era began for us all in September and October of 2019, with the introduction of a new element that is likely to become one of the dominant investment market influences in the 2020s.

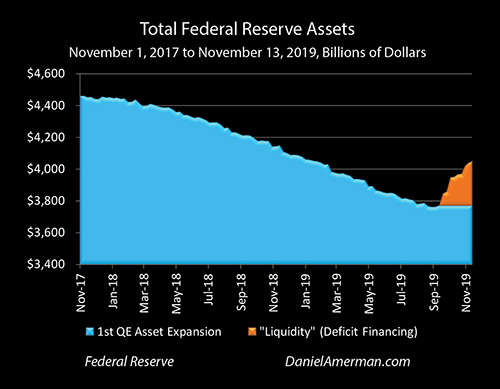

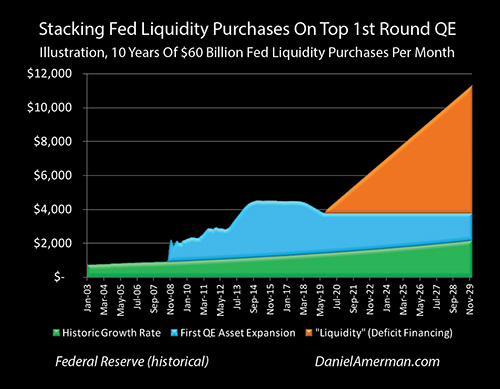

What is shown in the orange area of the graph above is something brand new. When we understand why the Federal Reserve abruptly reversed course, created $280 billion in new money in two months and injected it into the financial system - then we can also explore why this new element could still just be getting started and could lead to quite different prices and risks for stocks, bonds and homes in the 2020s, making the new decade entirely different from the 2010s or any previous decade.

Already $23 trillion in debt, the U.S. government will have a voracious need for cash in the 2020s. Ordinarily, a government in this situation would have to pay steadily higher interest rates to get that money. But, the federal government can't afford to pay higher interest rates without the annual deficits and the national debt exploding upwards, as explored in the previous chapter.

Entirely separately, and as explored in numerous previous chapters - the Federal Reserve's main tool for maintaining financial stability is that of interest rates. The Fed has its own quite different existential need to maintain very low interest rates - or to even rapidly force them much lower at will.

However, if the federal government sucking staggering sums of cash out of the markets on a monthly basis over the coming years ever sends interest rates spiking upwards - as almost happened in September - then the Fed's ability to maintain stability could collapse, along with the basis for the currently elevated values of retirement account investments and homes across the nation. On the other hand, as also explored in previous chapters, the process of maintaining stability could lead to still higher home and stock prices.

As of the fall of 2019, the day has arrived when the financial impact of the national debt on average savers and investors is no longer theoretical, but rather something that has the potential to radically change home prices, retirement account values and financial security for the average person in any given month or year - and the real time linkage that can cause these losses or gains is not some distant default or round of hyperinflation.

While everyone is at risk - the great majority of the population does not yet understand the new direct linkage of deficits to their financial security, the very real current dangers - or the counterintuitive ways in which the soaring national debt could actually act to increase the household net worth of the nation (for at least a time). They need to - or the risk is a "blindside" to the lifestyles and retirement plans of many tens of millions of people that could be larger and more enduring than the financial crisis of 2008.

This analysis is the 18th chapter in a free book. The earlier chapters are of essential importance for understanding the linkages between interest rates, home prices, stock prices, and bond prices; as well as how the Fed's heavy-handed interventions have already changed the fundamentals of investing. An overview of some key chapters is linked here.

An Interest Rate Spike & An Abrupt Reversal

The first problem occurred during the week of September 16th, 2019. The base issue is that in order to fund spending, the government needs to pull massive amounts of money out of the US economy on an ongoing basis. This money needs to come out in one of two forms, either taxes or deficit borrowing. In the week of September 16th - both were hitting simultaneously.

Third quarter corporate withholding taxes were due, which was the tax side.

It was also settlement day for a recent Treasury auction that had involved new funding for the government. This is crucial because a lot of Treasury sales involve rolling over existing borrowings, so the money comes out to investors from the Treasury paying off the old borrowings, that means the money is there for investors to buy the new obligations, and on a net basis - the government is not pulling its spending money out of the private economy.

However, on a simple basis (there are always levels within levels when it comes to government accounting), when the government is spending more than it takes it in from taxes, then it needs the cash to do so, and that cash comes from the private sector (or other sources), in the form of new debt sales. So, to the extent that the government runs ongoing deficits - those are funded with new cash that has to come in from somewhere.

Estimates vary, but in September of 2019, somewhere in the neighborhood of $100+ billion had to pulled out of the private sector, and much of that money for corporate withholding taxes and funds to purchase new Treasury obligations to finance deficit spending was "parked" in the repo market, lent to financial institutions at very low interest rates.

Then in October of 2019, about $134 billion of net new Federal borrowings needed to be funded. And that money had to come from somewhere, as did the money for November.

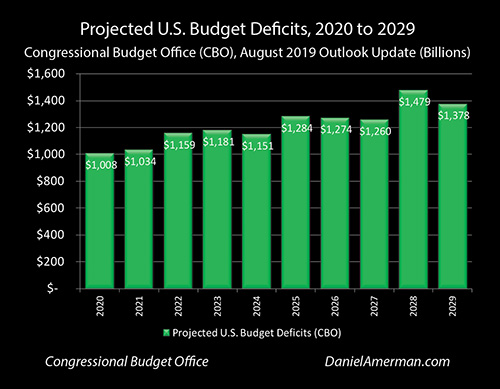

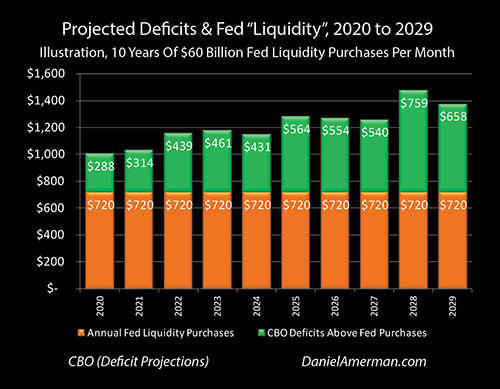

The graph above is based upon Congressional Budget Office projections, and it shows that during the 2020s, the U.S. government plans to have annual deficits above $1 trillion every year. Every single year, the U.S. government intends to spend at a trillion dollars more than it will collect in taxes - that is the base case if everything goes as planned, not a stress test - and that means that it has to get at least a trillion in cash from somebody or somewhere, each and every year without exception. (And that is before some of the extraordinary promises for future spending that are being proposed in an election year.)

When we look at the deficits on a cumulative basis, then the plan is to spend about $12.2 trillion more than is taken in through taxes over 10 years. So, the plan for the 2020s is for the Federal government to pull an average of about $102 billion in cash out of the financial system each month.

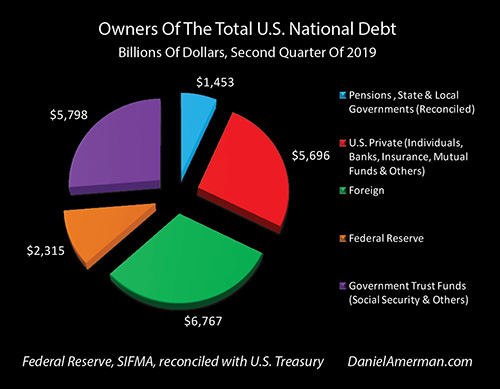

Furthermore, unless the money is coming in from the "outside", i.e. foreign governments or investors, or the Social Security & other Trust Funds, or the Federal Reserve, then the money needs to come in from somewhere in the U.S. private sector, whether that be financial institutions, corporations or individual savers.

It is worthwhile to compare the size of the red slice in the "pie" above, to the cumulative total of planned deficits in the 2020s. The total ownership of U.S. Treasury obligations by individuals, banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, and other private investors is "only" about $5.7 trillion. So, unless the money comes in from somewhere else - then the base plan to run $12.2 trillion in deficits in the 2020s means that the federal government intends to borrow about 214% more money from domestic nongovernmental sources than it has borrowed over the entire previous existence of the nation (on a simple basis, not adjusting for inflation).

This is a fantastic sum of cash that the government plans to pull in from the rest of the nation. Just as one comparison - it greatly exceeds the total of all student loan debt outstanding, all auto loans outstanding, and all credit cards outstanding. So if everyone took every dollar of student debt they owed, everything they owed on their auto loans and every dollar they own on their credit cards, then all of that together for the entire nation would not even be close to how much cash the federal government intends to get from us all via borrowing during the 2020s.

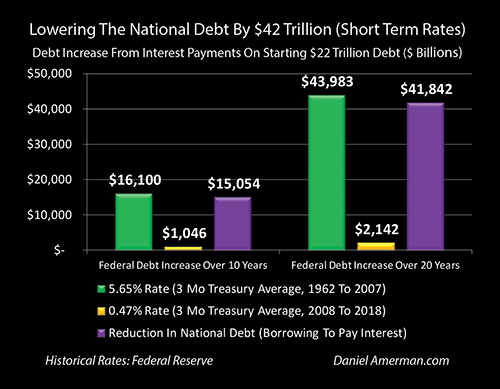

As explored in the previous analysis, if the interest rate on the national debt were currently at long term historical averages - averages for a much less indebted nation - then that by itself would be enough to add another $15 trillion to the national debt over the next ten years, not including any other deficit spending. This would be on top of the $12 trillion in CBO projected deficits, and would then radically increase the amount of cash the government would need from investors and the financial system each month.

(How the national debt and changes in interest rates work is actually a good bit more complicated than that because of the weighted average life of the national debt, but it is still fair to say that a rapid increase in interest rates would rapidly increase deficits which would rapidly increase the need for still more cash, and could thereby set off still more interest rate increases - and still higher deficits - if the national debt were being financed in a free market.)

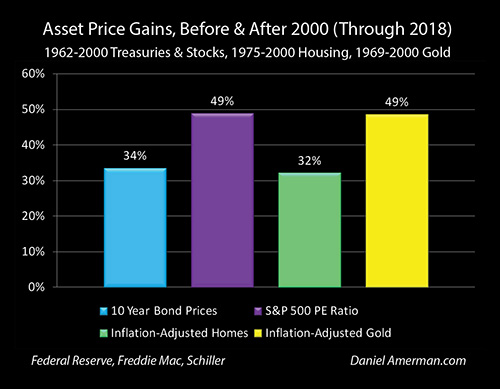

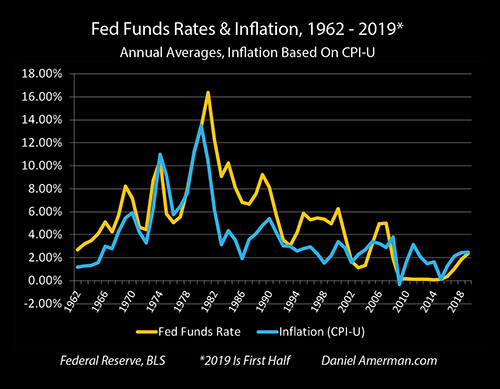

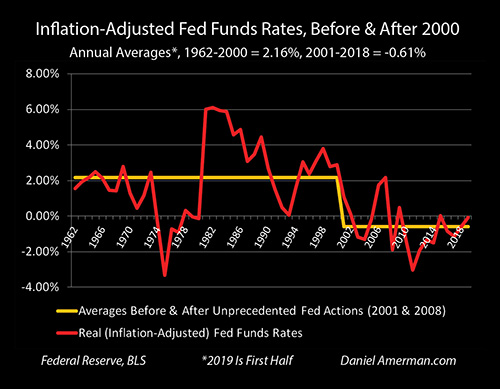

An entirely separate but equally existential issue for individuals and the nation is that as shown above and extensively developed in previous chapters, we currently have asset values for bonds, stocks and homes (as well as gold for separate reasons) that are at levels that are far above historic averages.

These highly elevated asset prices are based upon - and dependent upon - what are very low interest rates by historical standards.

And indeed, as introduced in Chapter One, our current very high stock and home prices are based on the maintenance of a quite unusual situation, that of negative real interest rates. When the rate of inflation is higher than the interest rate paid, then investors lose purchasing power each year. This is an unnatural state for investors - but yet, the Fed has on average been maintaining this state since 2001, and our current retirement account and home values are effectively dependent upon the Fed maintaining this unnatural state into the future.

Now, what makes this unnatural situation persist over time is to have lots and lots of "liquidity". The need is to have an abundant supply of money, with free cash sloshing around all through the system. So long as there is enough cash floating around, much of it goes to where the Federal Reserve (acting as both regulator and monetary authority) has set up the system to encourage it to go - which is to short term Treasury bills, the repo market, and fed funds at rates that are far below historic averages.

However, the danger is that when the U.S. government is acting as what could be likened to a gigantic vacuum cleaner, voraciously sucking that free cash out of the financial system in order to fund its deficit spending, the government might pull so much cash out that in any given month - or day - that the remaining free money floating around in search of a home might not be in great enough supply to fund the debt and other short term borrowings at the irrationally low interest rates that the Fed is counting on. That would be a real problem. And that brings us back to the fall of 2019.

Sucking The Excess Liquidity Out Of The System

A routine job for a corporate treasurer or a banker is to maximize the "float earnings", the daily return on cash right up until the moment the cash is spent. The corporations that had taxes due on September 16th, and the entities that had bought new Treasury obligations and needed to pay for them at settlement - each needed the liquid cash to do so. And a very common place to "park" that money right up until the moment it needs to be spent is in the "repo" market.

The "repo" or repurchase agreement market is not something that most individuals are familiar with - but it underpins the U.S. financial system, and is an extremely important source of cash for many banks and institutional borrowers.

A repurchase agreement is essentially a secured loan, that is legally a sale. Collateral - generally U.S. Treasury obligations - is sold to a buyer (who is effectively a lender). There is a simultaneous agreement at the time of the sale to repurchase the collateral at an agreed upon price and time, which is usually the next day. The difference in price between the sale price and the contractual repurchase price is effectively the repo rate of interest, which is generally close to the Fed Funds rate for overnight repurchase agreements.

Institutions who need cash enter in repurchase agreements with institutions who have excess cash, and this happens behind the scenes on a massive basis everyday in the U.S., and indeed it underpins the liquidity of the U.S. financial markets and the major participants. It usually works flawlessly, and the markets - and the stability of the U.S. financial system - depend on this happening.

Now while the repo market is generally overnight lending, many financial firms use it as an ongoing source of funding. They have to repay the money each day, and they may not actually have the cash to do so. Instead, they rely upon being able to borrow through a new repo agreement, every day, to repay the money they borrowed via the repo agreement from the day before. This is generally a seamless and absolutely reliable process, and while the interest rate varies on a daily basis, they count upon the money being there and within a certain reasonable range in terms of interest rates.

The week of September 16th, the repo borrowers had to give the lenders their money back, so the U.S. government could pull its $100+ billion in cash for the week out the financial markets, and fund its deficit spending. No problem, the repo borrowers turned to the repo market to borrow the new cash so they could repay the previous day's loans, like they did every day - only this time, the money wasn't there.

Uh oh.

The repo borrowers absolutely needed the new money coming into the repo market in sufficient amounts to replace what was going out to the U.S. government (ultimately), or they could default. The interest rate - which was supposed to be below 2% went to 3%, and 6% and even (very briefly) went to almost 10%, as repo borrowers scrambled to find a way to get enough new cash to come into the repo market to replace what had to go out in a matter of hours.

In other words, the liquidity ran out, in that one crucial market. And without the liquidity - the Fed's effective ability to force very low interest rates on the nation ran out, even while the stability of the financial system was being imperiled.

Now, while the average person likely has no idea that any of this happened (or even what a "repo" is) - the sum total of the nation's stock portfolios, retirement accounts and homes were all teetering on the edge that week. The Federal Reserve - very briefly - lost control of interest rates in one critical market, as a result of not properly understanding how the U.S. government's voracious consumption of cash to finance deficits would suck more liquidity out of the system than the Fed's economists thought it would.

Another way of phrasing this is that the Federal Reserve thought there was more excess liquidity in the system than there was, they thought they had ample safety margins to handle what they knew perfectly well was coming the week of September 16th - and it was the U.S. government removing $100+ billion in cash from the system in practice in that particular week that exposed the error in the Fed's models. (That is the problem with the modeling of complex systems that haven't been tested, particularly as an increasing number of pressure points further increase the complexity even while decreasing the tolerance for errors.)

Current stock, bond and house prices in the United States are all based upon not just very low interest rates, but the market's confidence that the Federal Reserve effectively has iron-clad control over those rates, and the ability to prevent an interest rate spike. If the markets lost confidence in the Fed, and thought free market interest rates were a genuine possibility, then the floor could fall out from underneath stock, bond and home prices, and this could happen in a swift and even catastrophic manner.

Of course, that isn't what happened, but what did happen instead is one of the main reasons why the 2020s will be a very different decade for investors and homeowners than the 2010s, and starting immediately.

Flooding The Financial System With Liquidity

Faced with a liquidity crisis in the repo market, the Federal Reserve created $53 billion in new money in an afternoon and directly supplied that money to the repo market. This was a very rare action, and it was the first time that the Fed had directly put money into the repo market since the financial crisis of 2008.

The Fed repos were immediately "oversubscribed", meaning that the amount that the Federal Reserve had intended to be more than ample, was not nearly enough. More financial institutions needed cheap overnight money from the Fed than it had realized. So the next round was to put $75 billion into the repo market on the next day.

These were intended to be very temporary emergency interventions, but instead the market grew dependent upon them. As of November of 2019, the repo market was still dependent upon the daily injection of extraordinary sums of money by the Federal Reserve in order to function normally and in the interest rate range desired by the Fed.

While very little noticed by the general population, the repo crisis had the full attention of institutional investors in September of 2019 and afterwards - because multiple ripple effects were in danger of being set off, that could have very negative consequences in multiple ways

However, there was a problem. The extraordinary Federal government deficits are not a "one off" - but are an expected and continuous factor going into the indefinite future, even as the Fed has an existential need for maintaining far below free market interest rates - also into the indefinite future - as part of the cycles of crisis and the containment of crisis.

The immediate problem is that while the September funding of $100+ billion in government cash flow could be funded by the Federal Reserve maintaining its new repo facility - the U.S. government's ongoing deficit spending would suck another $134 billion in cash out of the financial system in October of 2019. And then more in November. Where was that going to come from - and at what interest rates?

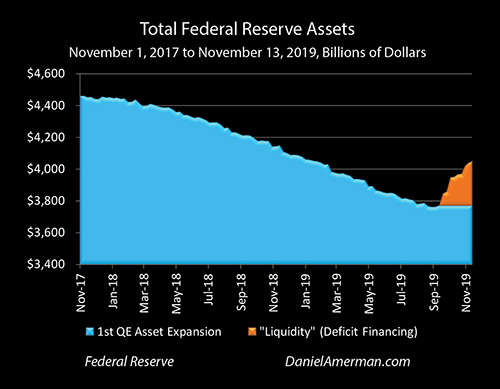

So the Federal Reserve scrambled and announced a quick emergency reversal of course. Their planned program of shrinking the balance sheet and reversing a previous decade of monetary creation, i.e. quantitative easing (QE), had already abruptly stopped earlier in 2019. As part of a quick and extraordinary pivot, the Fed committed to a new program of rapid balance sheet expansion, and began purchasing $60 billion per month of short term U.S. Treasury obligations, in a program that will extend at least into the second quarter of 2020.

When we add together the two new liquidity components of 1) the Fed creating money to stabilize the repo market, and 2) the Fed also creating money to buy $60 billion per month of U.S. Treasury obligations (from the markets and not the Treasury) then we get the orange area above.

This creation of $280 billion in new money in two months offset 40% of the Fed's $690 reduction in its balance sheet, that had taken eighteen months to achieve. All those years of talk about how the Federal Reserve would slowly unwind its QE monetary creation from its last round of the containment of crisis (as covered in Chapter Eight) - all went out the window, and without even any form of crisis that the general public was aware of.

When we take just the $60 billion per month and extend it over the next ten years, then we get the illustration graph above, which is based upon the earlier graph of CBO projected budget deficits. The new monetary creation works out to $720 billion per year, and it could be the critical component when it comes to enabling the ability of the U.S. government to suck out over a trillion dollars per year in new cash out of the system - without sending interest rates soaring upwards.

Of course, this is just an illustration - the Federal Reserve has not announced any ten year plans in this regard. On the other hand, given that "the Rubicon has been crossed", if the market does grow dependent on ongoing Fed liquidity injections to at least partially offset the U.S. government voraciously pulling liquidity out of the system in order to fund its planned budget deficits - when and how does this stop? And given the increasing size of the projected future deficits - are the liquidity injections more likely to go below - or above - the level $720 billion per year that is shown?

Accepting that specifics in practice are likely to vary from the smoothed illustration shown, if continued over ten years, this would mean that $7.2 trillion of the planned $12.2 trillion in budget deficits would effectively be covered by monetary creation, even if the money is never (for several good reasons) sent directly from the Federal Reserve to the U.S. Treasury.

This would leave an additional $5 trillion of deficit financing that would need to come in from other investment sources, and whether that would happen at very low interest rates that are likely to be below the rate of inflation remains to be seen. However, the chances of bringing in $5 trillion in new money at very low rates has to be seen as being much higher than the chances of bringing in over $12 trillion at irrationally low interest rates.

Now, let's return to our graph from Chapter Eight, the historical and future size of the Federal Reserve balance sheet, and add in the orange of ongoing liquidity injections / monetary creation at a rate of $60 billion per month.

In this graph, I've separated the green area of the historic growth rate in Federal Reserve assets, from the blue area of quantitative easing that was associated with the prior cycle of the containment of crisis. As covered in Chapter Eight, despite the solemn assurances of the Federal Reserve in 2008 that this extraordinary policy of creating money effectively from the nothingness and using it to directly move markets would be used only on a short term basis in dire emergencies - the increase in power for the Fed was too much to give up, and the Fed kept expanding its assets as it found new uses for monetary creation.

With the full recovery of the economy, the Fed really was supposed to wean itself and the markets off of relying on this emergency tool. However, as can be seen in the shrinkage of the blue area above, the Fed was only able to travel a relatively short distance on the return to normality, before abruptly stopping in the summer of 2019.

As shown, if the planned creation of $60 billion per month in new liquidity were to continue over time, then this effective partial funding of the budget deficits while keeping interest rates far below what a free market would demand, will fundamentally change the nature of the Federal Reserve, its balance sheet and the U.S. dollar itself.

The National Debt Supercycle Asserts Dominance

Had interest rates soared in September and October, this would have had devastating consequences for stocks, bonds and homes. Indeed, many trillions of dollars of household net worth could have already been lost, if the Federal Reserve had not intervened with extraordinary acts of monetary creation on an emergency basis, creating $280 billion in new money, and injecting it into the system to flood the markets with new cash.

This isn't a distant theory, this is right now, and this is likely to not only continue but to grow ever stronger in the coming years. Our world has genuinely changed, and the extraordinary acts of fiscal discipline and political willpower that would be needed to reverse direction - don't seem to be anywhere in sight. Instead, it is quite the reverse, as presidential candidates compete to buy votes by promising spending could exceed what is shown herein by fantastic margins.

To the extent they think about it at all, many people seem to see the national debt as being some abstract concept or political issue that has no impact on their day to day lives. They would not even dream of changing their savings or retirement account decisions to take a $23 trillion national debt into account, the very idea of doing so would be just completely foreign to them. (Unfortunately, these people will be in for one heck of a surprise at some point, and perhaps much sooner than they think).

For the many millions of people who do care deeply, and who do recognize just how surreal and short-sighted it is for the United States to be running $1+ trillion a year deficits on top of a $23 trillion national debt, it seems that they often see the national debt in very negative terms and with a life changing price to be paid - at some point down the road. There could be a future default, or a future round of hyperinflation, but in the meantime, before the collapse arrives, they usually don't seem to see any connection between their current financial decisions and planning, and what is happening with deficits or the debt.

If the reader will permit, let me quote myself from an analysis on this subject in May of 2014.

"In some ways, the current extraordinary level of federal debt could be likened to sharing our solar system with a financial black hole. Just because people aren't seeing it every day – doesn't mean it isn't there. Whether seen or not – the massive gravitational pressure dominates everything around it.

And every time someone saves, invests, retires or makes a major purchase – the massive weight of that $17.5 trillion debt pulling interest rates down through the corresponding governmental interventions impacts their life, right that minute.

...While this massive weight affects every part of society, there is one group that is more affected than any other. That group is the people who are following traditional retirement planning or other long-term investment strategies."

This has been on the way. What happened five years later in September and October of 2019, was that the rapid growth of the black hole, the staggering monthly amounts of cash that deficit spending is pulling out of the system - nearly reached out and pulled us all in. To continue the analogy, the surprised crew of our starship at the Fed were asleep on the job, their navigation model did not properly account for just how much liquidity was being pulled out of the system and it was only the emergency change in course and application of $280 billion in monetary creation "rocket fuel" (so far) that allowed us to break free.

I do realize that for most people, changes in total federal reserve assets sounds highly theoretical, with an excitement factor that falls somewhere between watching paint dry and watching the grass grow. Hopefully, using the analogy makes the orange area above a little more clear in terms of why it happened, how close we came, the radical change in course, and why the Federal Reserve is pouring on the rocket fuel in the attempt to climb out of the danger zone.

As the cumulative result of decades of irresponsible political and monetary decisions, we are in very interesting times as the 2020s approach, and there is nothing theoretical about just how quickly the success or failure of those emergency maneuvers could change the day to day lives of many millions of people - who by and large have absolutely no idea that any of this is happening.

A Predictable Collision

In confirmation of the predictable nature of something like this happening - and why it is likely to be far more important in the coming years, transforming the 2020s, I would like to also offer the quote below from an analysis I wrote and published in March of 2018.

"The United States government has a voracious need for new money - but with an over $20 trillion debt, it can't afford to pay higher interest rates over the long term. The Federal Reserve is currently going through what could be called a market liberalization cycle, or a quantitative tightening cycle, where it reduces the supply of artificial money, and lets the market fund more of the federal debt with real money at higher interest rates.

That is a daunting task - how to get huge sums of money without paying whopping interest payments that would send the national debt upwards and out of control. How are the U.S. government and Fed going to do that? Is there a well thought out and brilliant plan for doing so?

Early indications as seen in the market this week, is that there is no plan, they have no idea how to do this, and they are just going ahead anyway. The government needs the money to feed a politically created major increase in deficits, so it is borrowing, the Fed's textbook says this is the time in the business cycle to raise rates, so it is raising, and the two trains are speeding down the track straight at each other.

The government just sold $126 billion of Treasuries on Monday - and it had difficulties, which meant it had to pay higher interest rates. That was before auctioning the $169 billion planned for later in the week, to fund the government's deficit driven need for about $300 billion in cash in a single week."

Whether we want to call it being pulled into a black hole, or the head on collision of two speeding trains - this has been coming in plain sight for a very long time, as I have been explaining to readers over the years.

However, what is much more important is what is on the way. What we know right now when looking at projected budget deficits is that unless there is some kind of major reversal of course, this will just get more powerful each year, and is likely to have an ever greater impact on stock prices, bond prices, housing prices and gold prices in each year, changing them in ways we never saw in the 2010s or previous decades. Starting in 2020 there are also growing implications each year when it comes to financial stability, and the chances of a crisis of potentially epic proportions.

(The March of 2018 public analysis with the collision between trains above also appeared in the "2019 Overview" DVD set and manual (pages 165-172) that was released in December of 2018, as being one of the critical changes that was on the way and to keep an eye out for, as well as being one of the conflicts that could cause the Fed to reverse course on interest rates and quantitative easing. Of course, the Fed did do so in 2019, with higher stock, bond and home prices being among the results. More information is available in the "Seven 2019 Scenario Results" linked here.)

Understanding The Linkage

In the previous seventeen chapters of this book in progress, I've worked hard to create a series of analyses that explain things like Federal Reserve policies, the economic cycle, interest rates in nominal and real terms and how they change home and investment valuations, the roles of quantitative easing and monetary creation - and how all of these are coming together to become dominant influences on stock prices, home prices, and bond prices in ways that we have not seen before, in practice and in real time.

My hope for those who have been reading along to this point - particularly for those of you who are not financial professionals - is that these essential factors are really starting to make sense, and that you are understanding the connections, as well as the very practical and even life changing implications.

Once those are understood - then something else can also be understood. That is what a $23 trillion national debt is really all about, the true systemic danger of endless $1+ trillion annual deficits, how those powerfully intersect with cycles of crisis and the containment of crisis - and how they are doing so right now.

For the average person, the immediate danger from deficits and the national debt is not government default or hyperinflation - it is setting off a potentially calamitous destruction of the value of their retirement accounts and homes. In order to see this - the linkage has to be understood - and hopefully this and the previous seventeen chapters have been helpful to you in seeing how all the various pieces come together.

This danger could be a number of years away - or it could be less than a year away. We are all living inside a highly complex system, in unprecedented circumstances, with many outside stresses. While the Federal Reserve has extraordinary monetary powers, we are already seeing that even in the early stages, the complexity and demands of the situation are at times surpassing the capabilities of the existing decision makers and the models they rely upon.

Learn more about the free book.

********************************************