SVB And Collapsing Global Financial Defenses

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetA major financial collapse occurred the weekend of March 11th - but it wasn't Silicon Valley Bank or Signature Bank.

After the Financial Crisis of 2008, the leading economic powers of the world spent years studying what went wrong, they decided how to cure the risks, and they solemnly agreed on the steps they would all take together take to make sure that it never happened again.

As we will review in this analysis, the U.S. Treasury Department and Federal Reserve just tossed all those agreements out the window in one weekend. The global defenses are gone, the risk of systemic financial crisis is up sharply, and Silicon Valley Bank is the least of our problems.

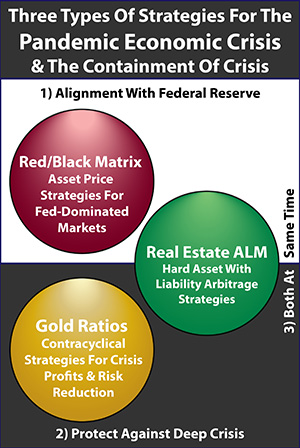

This analysis is part of a series of related analyses, which support a book that is in the process of being written. Some key chapters from the book and an overview of the series are linked here.

The Lessons Of The Recent Past

Let's go back to 2009. The world had just barely escaped total global financial meltdown. Every major bank in the West could have collapsed, along with the international financial system.

The leading economic powers of the world did not want to see this happen again. So, beginning in 2009, they decided to restructure the global banking system to prevent a repeat. This was a multiyear process, that became the Basel III international banking accords. While the accords are still being implemented, most of the major changes were put in place between 2010 and 2015. As the leading global financial power, the United States was of course at the center of developing and implementing these new banking regulations.

What the risks were and how banking could be restructured to prevent a financial meltdown were intellectually developed over a multiyear period, and in 2012 there was an IMF Staff Discussion Note released that was titled, "From Bail-Out To Bail-In: Mandatory Debt Restructuring Of Systemic Financial Institutions". In that lengthy "Note", the staff economists at the International Monetary Fund did a particularly good job of summarizing the sources of risks, the dangers from those risks, and how to remove the risks.

As long-time readers may(?) recall, I thought this was vital information for people to know, so in 2013 I published a lengthy analysis (link here) of how banking was being transformed and the new risks for depositors. Ten years later, those risks that had been there all the time have now become the stuff of shocking headlines. Indeed, if we want to understand what has been happening in this past week, as well as the dangers of a new financial crisis, the intellectual framework for understanding what is happening has been there the entire time.

For those who haven't read or don't remember the analysis, I would recommend reading the original, but here are some key sections that are relevant for today. These are risks to the system from Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs):

"As covered on document page 4 (PDF page 5), there are three different ways in which the failure of even a single SIFI can imperil the entire global financial order.

The first major risk is "direct counterparty risk", with the SIFIs having an extraordinarily complex web of hundreds of trillions of dollars of interlocking commitments and contracts between themselves. The failure of a single SIFI could trigger a chain reaction of losses that would spread like dominoes, knocking down one SIFI after another – as well as other banks and investors around the world.

The second major risk is one of "liquidity". Since SIFIs rely heavily on borrowing, if the sources of their funds flee in the event of trouble, this would leave the SIFIs potentially insolvent unless they could quickly sell assets to cash out departing lenders, which would rapidly drive down prices, and with everyone selling assets together this could create a global "fire sale" on investments that's enough to crash the world's financial system in a matter of days.

The third major risk is one of "contagion", where the failure – or even looming failure – of one major institution introduces a psychology of panic into the marketplaces, which by itself is more enough to bring down the global financial order. After all, perception can and does create reality when it comes to financial markets.

Now all of these risks received a great deal of attention after the global banking system nearly went under in 2008, and in theory they were supposed to have been taken care of by restricting the ability of the SIFIs to take risks, and also by reducing the percentage of the world's financial assets that are held by the SIFIs.

However, as covered at the bottom of page 4 (PDF page 5) – this hasn't been working out in practice.

To the contrary, there has been an even greater consolidation of assets into these "too-big-to-fail" banks and financial institutions than there ever was before the crisis started. As a result, this has created "unsustainable public finances", where the extraordinary cost of conventional bail-outs potentially threatens the solvency of the nations themselves. And such a sovereign insolvency could in turn trigger insolvency for the SIFIs. So again we have a toxic feedback loop between the SIFIs and the nations that must bail them out in the attempt to avert global financial collapse."

"Plainly put, the existing laws can't handle the problems that have been created by this intertwined world of "too-big-to-fail" institutions that continue to take massive financial risks for private gain, seemingly beyond the control of the sovereign nations, even as the sovereign nations dealing with their own financial problems increasingly lack the credible financial resources to massively bail-out these institutions without risking their own solvency. So the bail-outs are unaffordable, but yet a failure to bail-out would lead to swift global financial chaos."

Back to the present in March of 2023. We just saw forms of all three big risks come into play simultaneously. There was liquidity risk: Silicon Valley Bank did not have the money to pay its depositors. There was counterparty risk: the failure of Silicon Valley Bank could have led to failures at venture capital firms and start-ups throughout the tech sector lost almost all of their cash. There was contagion risk: Signature Bank immediately failed as well, and share prices were hit hard for some regional and small banks around the nation.

These risks are not new or unique. The risks have been studied in great detail, all three were also in play in 2008, and they are the classic prescription for creating a financial crisis. The specific forms the risks take differ with each round, but the underlying risks remain the same.

The Bail-In Solution

The economists of the world did find a solution to these seemingly impossible problems which was to replace bail-outs with bail-ins, as described below:

"One way of looking at a bail-in is that it is the opposite of a bail-out. In the case of a bail-out, when there's an issue with a bank (or government, or government retirement system) not having enough assets available to meet the claims against it, funds are brought in from the general public, supposedly to serve the needs of the general public.

With a bail-in, there is no bankruptcy, but assets are taken from selected investor classes, thereby reducing the claims against the corporation.

Solvency is therefore achieved and the needs of the general public are met, but without the general public having to actually pay for it.

Now while the IMF document uses the term "bail-ins", they also offer a quite different way of explaining the process, as shown on page 7 (PDF page 8). As stated, "the bail-in capital could be seen as a form of insurance (provided by creditors) against bank insolvency".

Now if we think through this approach – this way of finding completely new solutions for a system that otherwise lacks solutions, the implications are global, and they are extraordinary.

The way it works is that in the event of a potential financial meltdown, the government – or international organization – identifies particular investment types and classes of investors. These investors hold assets, and in some cases these assets are the liabilities (such as bonds) of the institution that is in trouble.

The government effectively says to these investors, "you may think that you own an asset, but what you've really done is you have underwritten an insurance policy. And if this institution in which you've invested your assets should run into financial difficulty, you have in fact pledged your assets to prevent the insolvency of the corporation, for the greater good of the global financial order".

Now the owner of the investment asset had no idea when they made the investment that they were doing this. They've never received an insurance premium for taking this risk. But nonetheless, a category of investment assets are retroactively declared to be insurance, and they can effectively absorb all the losses and keep the SIFI – or the government, or the public retirement system – solvent for the benefit of all."

Bail-ins have been the law of the land in the United States since the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act of 2010. According to the law, the way the financial defenses of the United States and the rest of the global financial system are set up, it is the shareholders and bond investors who are supposed to get wiped out in a bail-in, and any remaining shortfalls will be covered by the uninsured depositors.

For financial professionals (as well as the more savvy members of the general public), this is basic, basic stuff. If a bank fails, then the insured deposits are guaranteed, but anything over the $250,000 limit for insured deposits is at risk of losses that could reach 100%. There are no surprises there, it is an open matter of the law. (Whether Silicon Valley as a whole was grossly incompetent or something else was in play will be explored in the next analysis in this series. "Smart but innocent" will likely be the Narrative, but believing this strains the limits of gullibility.)

For fifteen years, this was the message that the United States was pushing to the rest of the world, the need to replace bail-outs with bail-ins. It also should be noted that this was particularly vital when it came to the SIFIs, the systemically important financial institutions. Obviously, there would be strong political pressures to bail-out instead of bailing-in in the event of crisis, but in order to prevent a potential global financial meltdown, the governments of the world had to promise each other that they would stand firm, and use bail-ins. The promises were made, as reflected in Basel III.

So, when an actual financial crisis began with what was on a global scale a relatively small bank - but with exceptionally politically connected depositors - what did the United States do? The government tossed fifteen years of work on assembling global defenses right out the window over the course of a single weekend. Banking regulators in Europe are reportedly furious on a behind the scenes basis, but what are they going to do about it?

The natural result is that there may be another contagion of sorts that is spreading, and this contagion is on the regulatory side. Credit Suisse is currently in trouble, as some other leading European banks may be as well. We don't know what will happen yet, but if they do go under, the rule book was supposed to be crystal clear. As a systemically important financial institution Credit Suisse is supposed to be bailed-in - with uninsured depositors taking losses as necessary - in order to preserve the financial system. However, now that the Swiss government has seen the US government abandon its promises as the opening move in this round of crisis - what are the chances that the Swiss will take the needed political damage?

What are the chances that the Germans will pay the political price to bail-in Deutsche Bank if needed, versus the much more politically palatable bail-out?

Unsustainable Public Finances

Back to 2013, and why the world agreed to move to bail-ins instead of bail-outs:

"The governments themselves are deeply in debt, the overall global economy continues to underperform, and many nations have far greater promises which have been made to their populations than they currently have the funds to pay, or are likely to have the funds in the future. So "stimulus" programs keep the global economies running, even as the debts continue to mount up.

And the leading source of government insolvencies over the long term is unfunded and unpayable government promises for retirement benefits.

So we have three separate but tightly interlocked components, with those being effectively bankrupt sovereign governments, effectively bankrupt public retirement systems, and a global system of major financial institutions who have entered into interlocking derivatives contracts, that are subject to collapse at any time when the next major financial stress hits the system.

All three are tightly interlocked; all three are dysfunctional. And the whole thing is held together by increasingly aggressive government interventions. Quantitative easing is of course a government intervention, and the "bail-ins" are another form of government intervention. These stresses grow worse each year as the populations of the United States, Europe and Japan continue to get a little bit older on average, even as the jobs for the young – that are needed to pay for those retirement promises – continue to fail to materialize.

This situation is entirely outside the current media message that the world is getting healthy again and these crises are receding in the rearview mirror. Instead they're escalating, and the system remains more at risk than ever, as covered in the IMF report.

However, despite five years of crisis – the financial order hasn't collapsed yet. And while it certainly could collapse at any time as a result of a political miscalculation, there's frankly no need for the global financial order to collapse. Indeed it could continue to exhibit a surprising stability over time – albeit a completely dysfunctional stability from the perspective of most savers and investors."

Back to 2023, and while it has been quite the ride since 2020 in particular, the global financial order did indeed "exhibit a surprising stability over time". The underlying problems have, however, gotten much worse than they were.

The U.S. national debt has shot up from $18 trillion to $31 trillion in just ten years - a shocking level of increase. The too-big-to-fail banks, which should perhaps be referred to as the too-big-to-politically-control banks, are bigger than ever, and it looks like they will get bigger still as money leaves the small and regional banks, to concentrate on the banks that create the risk of systemic financial meltdown.

In both the United States and Europe, aging populations have created even more pressures on public spending, compared to ten years ago.

There seems to be some sort of reckless and accelerating process in play. There was the fantastic increase in the national debt during the pandemic. Then money was no object when it came to attempting to forgive hundreds of billions of dollars in student loans - without even a congressional vote. Money is no object when it comes to aid to Ukraine.

This is all happening in the context of Russia, China, India, Saudi Arabia and many other nations trying to assemble a parallel financial system, that will free them from dependence on the dollar and the Western financial system. (There is also the consideration during this time of Great Power strife that if the Western financial order is teetering - will a rival such as China give it a shove?)

Then trouble came, and in just a single week - the United States jettisoned the primary defense of the global financial system against collapse, even while it may have created an implicit guarantee for the entire $17.6 trillion in bank deposits, effectively promising to bail-out rather than to bail-in.

Politics As A “Defense”

I’ve never liked bail-ins. That is why I’ve warned people about bail-ins for the last ten years, so that they wouldn’t make the same mistakes that were made with Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

That said, I’ve always understood why bail-ins existed - they were a clever workaround for a politically corrupt system. The fundamental fix has always been the same – simply break up all the systemically important financial institutions. Take all the JP Morgans, Goldmans, and Citibanks and break them up into 20+ smaller institutions. The IMF staff economists knew this as well, but they know their place in the global pecking order, and they did not want to upset their masters.

Mega banks create mega profits through essentially unfairly dominating the global financial markets, with a heft and power that smaller, more competitive banks do not have. Oligopolies are more profitable – particularly for insiders – than the more economically desirable ideal of perfect competition.

Banks themselves are by their very nature highly leveraged, debt is the source of their money. High leverage oligopolies inherently carry huge systemic risks. An inevitable side effect of having mega banks is that the system can blow up at any time if they fail. All of us individually then, the populations of the nations, every day carry the risk of catastrophic financial wipeout not because it is necessary, but because it is more profitable that way for those who matter, those with money and political power.

This was made abundantly clear in 2008 – and it was never fixed. The people who blew up the financial world kept right on going, making more money than ever, because in the real world the financial safety of the voters and average people is not even a serious consideration compared to the insider relationships between the mega banks and the highest levels of our political system. Unfortunately, when problems don’t get fixed, they get worse.

This framing is necessary for understanding what is happening day by day in the current crisis. Forget the Narrative in the corporate media, the good of the public is way down the list when it comes to what is governing the actions of the government, the regulators and the big banks. Yes, they don’t want to blow the system up. But, there are no regulators or bankers burning the midnight oil trying to save the public. Rather, they are trying very hard to save themselves – first and foremost – and they will choose riskier options that are better for them, instead of safer options that harm them.

The global bail-in regime that was devised by academics and staff economists was based on a theoretical world of virtuous governments making the necessary tough choices, and it did not survive its first contact with the real world. The first major decision in the current crisis was to dismantle the defenses of the public – because that benefited the people who mattered. Reducing the size of the big banks is existentially necessary for the good of the public, yet, the big banks are growing larger, more powerful – and riskier – instead, as deposits flood into them.

As events continue to develop over the coming days and weeks, it is important to keep in mind that there are two distinct types of risk in play. One risk is the risk that we get another round of global financial crisis. The second risk is whether the current financial system can survive such a crisis, if it does arrive.

It is this second level of risk that has been increasing over the last ten years and has now gotten quite a bit worse just in the last week. Again the framing is everything – the choices made did not decrease the chances of catastrophe, but increased the chances instead, because they were willing for the public to take that chance if it financially helped key political constituencies.

These choices do not increase the chances for a near-term crisis, but they do mean that the chances of a catastrophe scenario are up sharply, in the event of a crisis. And if such a catastrophic crisis does hit - there's a good chance that we come out on the other side with a global financial order that is no longer based on the dollar or euro, with lifelong implications for us all.