Economic Fragmentation And Dollar Hegemony

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetWe’re having another of those kinds of weeks again, when more can happen in a week than sometimes happens in years. The last week like this was just last month when Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and the systemically important Credit Suisse all failed. To have weeks like this occur for two months in a row is… worth noting.

This week could be bigger when it comes to the long term investment markets, as well as our standards of living. In a speech given on April 17th, Christine Lagarde, the President of the European Central Bank and former head of the International Monetary Fund, has joined Janet Yellen, current U.S. Treasury Secretary and former Fed Chair, as well as former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers in using a new vocabulary.

Three eminent macroeconomists and powerful insiders are now very publicly discussing the rapidly evolving fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, as well as the potential for the loss of dollar hegemony. These developments have, of course, been in process for some time, but we now have policy makers formally acknowledging that the world economy is in the throes of fundamental change, the biggest we have seen since the end of the Cold War. This is not a fire drill, this is not idle speculation, we are witnessing major changes in real time.

This analysis is part of a series of related analyses, which support a book that is in the process of being written. Some key chapters from the book and an overview of the series are linked here.

“Central Banks In A Fragmenting World”

The full speech from Lagarde can be found on the website of the European Central Bank, and is linked here.

Let’s look at some key quotes, and then examine some of the implications. In the quote below, Lagarde discusses the fragmentation of the global economy:

“The global economy has been undergoing a period of transformative change. Following the pandemic, Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine, the weaponisation of energy, the sudden acceleration of inflation, as well as a growing rivalry between the United States and China, the tectonic plates of geopolitics are shifting faster.

We are witnessing a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, with each bloc trying to pull as much of the rest of the world closer to its respective strategic interests and shared values. And this fragmentation may well coalesce around two blocs led respectively by the two largest economies in the world.”

Lagarde also quite explicitly mentions the possibility of the related changes in international currency reserves.

“In the time after the Cold War, the world benefited from a remarkably favourable geopolitical environment. Under the hegemonic leadership of the United States, rules-based international institutions flourished and global trade expanded. This led to a deepening of global value chains and, as China joined the world economy, a massive increase in the global labour supply.”

“But new trade patterns may have ramifications for payments and international currency reserves.

In recent decades China has already increased over 130-fold its bilateral trade in goods with emerging markets and developing economies, with the country also becoming the world’s top exporter.[13] And recent research indicates there is a significant correlation between a country’s trade with China and its holdings of renminbi as reserves.[14] New trade patterns may also lead to new alliances. One study finds that alliances can increase the share of a currency in the partner’s reserve holdings by roughly 30 percentage points.[15]

All this could create an opportunity for certain countries seeking to reduce their dependency on Western payment systems and currency frameworks – be that for reasons of political preference, financial dependencies, or because of the use of financial sanctions in the past decade.”

Crucially, Lagarde discusses a world of greater instability, lower growth, higher costs, repeated supply shocks, and the acute supply vulnerability of Europe and the United States.

“But that period of relative stability may now be giving way to one of lasting instability resulting in lower growth, higher costs and more uncertain trade partnerships. Instead of more elastic global supply, we could face the risk of repeated supply shocks. Recent events have laid bare the extent to which critical supplies depend on stable global conditions.

That has been most visible in the European energy crisis, but it extends to other critical supplies as well. Today the United States is completely dependent on imports for at least 14 critical minerals.[3] And Europe depends on China for 98% of its rare earth supply.[4] Supply disruptions on these fronts could affect critical sectors in the economy, such as the automobile industry and its transition to electric vehicle production.”

For me, the most interesting part of Lagarde’s speech was the following:

“We have clear examples of what not to do when faced with a sudden increase in volatility. In the 1970s, central banks faced upheaval in the geopolitical environment as OPEC became more assertive and energy prices that had been stable for decades ballooned. They failed to provide an anchor of monetary stability and inflation expectations de-anchored – a mistake that should never be repeated for as long as central banks are independent and have clear price stability mandates.

So, if faced with persistent supply shocks, independent central banks can and will go ahead with ensuring price stability. But this can be achieved at a lower cost if other policies are cooperative and help replenish supply capacity.

For example, if fiscal and structural policies focus on removing supply constraints created by the new geopolitics – such as securing resilient supply chains or diversifying energy production – we could then see a virtuous circle of lower volatility, lower inflation, higher investment, and higher growth. But if fiscal policy instead focuses mainly on supporting incomes to offset cost pressures (in excess of temporary and targeted responses to sudden large shocks), that will tend to raise inflation, increase borrowing costs and lower investment in new supply.”

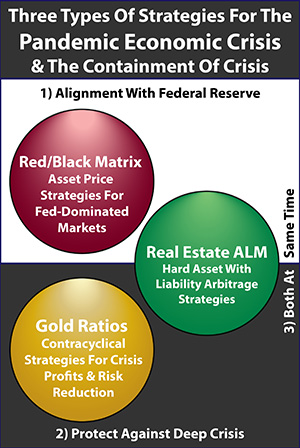

The reason I was so interested is that I was familiar with the concepts as I had been writing them out in detail over a period of weeks while getting prepared for my upcoming workshop. There are reasons for the similarity.

Making important financial decisions for most people is often a matter of experience and pattern recognition. We get experience living in the world as it is. We recognize patterns in terms of what works and does not. People learn what works in terms of making money, whether it be in stocks, bonds, real estate, precious metals, or their particular business, and they also find out where the risks are.

This experience-based pattern recognition usually works pretty well, with one glaring exception. That exception is when there is an economic or financial change that is so fundamental that it just pulls the rug out from underneath the way the world used to work. With such a fundamental change, at least a part of the experience-based pattern recognition from the “before times” becomes useless or even dangerous.

As long-time readers know, my usual position when it comes to Lagarde or Yellen is to disagree with them, or to criticize their actions (Summers is a bit more complicated). However, in this particular remarkable week, I find myself in full agreement with Lagarde, Yellen and Summers – the rug pull is in process, it is happening for real, and a lot of what was valid experience-based pattern recognition is now obsolete.

The reason for the similarities between Lagarde’s brief public overview and my presentation notes work-in-progress is that we are both identifying some of the fundamentals that are changing. We’re seeing the same “rug pull”.

1. Inflation. Inflation works in a fundamentally different way with competing fragmented economies with interwoven supply chains that are geopolitical competitors, even as there is an attempt to separate the supply chains while seeking to maintain currency reserve status. The “before times” didn’t have any of this, the path ahead is quite different.

2. Interest Rates. When Lagarde talks about “ensuring price stability” while avoiding the mistakes of the 70s, it is best to listen to her very, very carefully. She is talking about interest rates and monetary policy, she and Powell are speaking the same language – and it is the opposite of what the markets are currently anticipating. If maintaining price stability is the foremost goal of central banks in the current high risk fragmented global economy, then that means the “before times” are gone, and interest rates have a quite different path ahead than what most investors currently believe.

3. “Securing Resilient Supply Chains.” There’s some more econ-speak, what does it mean? What those four words mean is that we are going to see fundamental changes to our economy, employment and careers in that economy, what industries succeed or fail, who will be wealthy, and what investments are likely to suffer or thrive over the coming years. The leadership of the West has belatedly realized that they’ve handed our economies over to an opposing geopolitical “fragment”, which can break the economies of America and Europe at will, simply by withholding our supplies. Whoops! That was a bit of an oversight, eh?

The only way out, economically speaking is to make radical economic changes, that will necessarily have radical investment implications. Rug pull!

In yesterday’s (4/18/23) analysis, “Thinking Through The Unimaginable: America After The Fall Of King Dollar” (link here), I provided some of my draft presentation notes that are intended to introduce the second day session for my May 13-14 workshop. Some of those notes do relate to what Lagarde refers to as “securing resilient supply chains”:

- Another way of phrasing this is that exorbitant privilege has created fundamental and pervasive distortions in the US economy and markets, and those distortions will necessarily need to be corrected as the US adapts to the loss of exorbitant privilege

- The end of the distortions could be catastrophic for some investments, careers and world views

- On the other hand, for those who are able to participate in the corrections through investments and/or careers, this time of upheaval can be a time of tremendous economic opportunity

- To identify the distortions and corrections, we will need to dive deep into something inherently unstable, which is the current components of GDP and trade balances - our economic system cannot pay for itself absent exorbitant privilege

- What the day to day standard of living for the average American is based upon - and most importantly how we as a nation actually pay for that - are quite different than how they are generally presented

- When we look at the *specifics* of imports and exports this morning, and compare them to the components of our internal GDP, what we will find is that what we produce internally and how we value it is fundamentally incompatible with what the rest of the world demonstrably wants from us - and it is only exorbitant privilege that has allowed this distortion to exist

- Correcting the distortion of an unsustainable trade balance is not rocket science, many nations have faced problematic trade deficits before, curing them requires increasing exports and/or decreasing imports

- As we will be reviewing, the implications for inflation and interest rates are also not rocket science, many nations have also been here before, but these implications are outside of the “Overton Window” for both the current general market assumptions and retirement financial planning, almost no one is prepared to handle what logically comes next if reserve status is lost

- Absent exorbitant privilege, we have to find ways to give the rest of the world more of what it actually wants (increasing exports)

- To correct will require changing our external balance of trade in a number of categories, which will require a fundamental rearrangement of the components of our internal GDP, some of which will be lucrative for those involved

- The other basic correction tool is for the US to reshape its economy to internally produce much more of what it needs (decreasing imports), which will also require a fundamental rearrangement of the components of our internal GDP

Those particular notes assume what Yellen and Lagarde now openly admit is possible but hope will not happen, which is the loss of the reserve status of the dollar. Even if that doesn’t happen, however, we will need to fundamentally redo how the international supply chain works, and that will fundamentally change the U.S. economy. Indeed, those same changes could be called the attempted defense of the dollar.

“Securing the supply chain” means fundamental changes in how the American economy works, and there will winners and losers when it comes to those changes. The last fifty years of experience won’t necessarily help us here – we’ve been going in one direction for those fifty years, a reversal in direction is being planned, and the time to think through what will be different is before it happens.

******************************************

The brochure for the May 13-14 workshop is linked below. There is still space available at this time.