The Unstable Funding For The National Debt

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetThe markets are currently facing a fundamental and growing source of instability - the funding for the national debt.

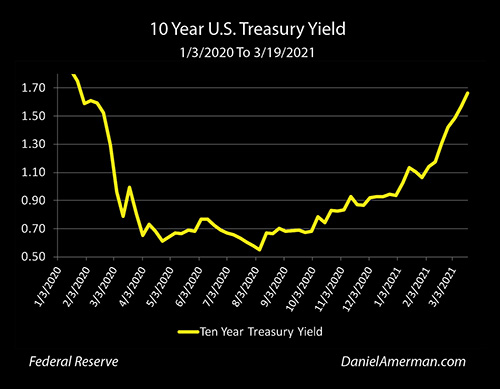

The yield on the 10 year Treasury obligation has been rapidly increasing, and on a weekly basis it has tripled since its floor in August of 2020, rising from 0.55% to 1.66% over the last seven months. This increase in interest rates has led to rising mortgage rates, and has been causing volatility in the stock market, particularly with Tech stocks.

As we will explore in this analysis - the fundamental issue is that the markets are sated, there is no more demand by investors to fund the U.S. Treasury, and this has been true since even before the pandemic. At this time, even the current funding for the debt is dependent on $1.6 trillion in "hot money", investors who have no long term interest in funding the national debt, and who are requiring higher and higher interest rates to keep their money in U.S. Treasury obligations.

Because the funding for the current $28 trillion national debt is not stable, even as still more trillions in new debt will need to be funded this year and next year - interest rates are not currently stable, and therefore neither are the price levels for the bond and stock markets.

This analysis is a brief outtake from my upcoming May workshop. For those of you who will be attending, this is a section of what we will be going through during the first part of Saturday morning, helping to set the stage for the rest of the weekend. For the many readers who will not be going to the workshop, we are living in times of extraordinary financial turmoil, the markets and the funding for the new stimulus as well the national debt in general are not at all stable, and hopefully this outtake will contain some useful information and perspectives for you.

Putting The Growth In the National Debt In Perspective

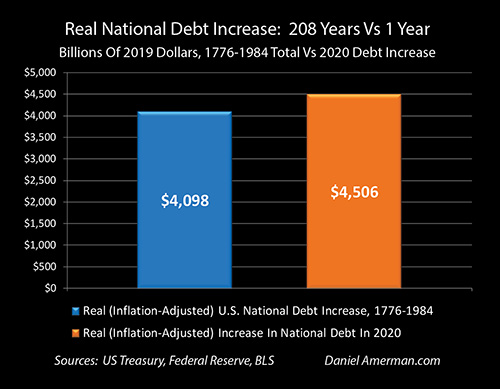

The increase in Treasury yields can best be understood by looking at the graph above. As explored in the analysis linked here, the United States government borrowed more money in 2020 than it did in its first 208 years in existence, and this is true even after adjusting for inflation.

The amount of money involved is staggering, to the degree that it is almost impossible for most of us to wrap our minds around it.

But as we will be exploring at this workshop, it is not only entirely real but our lives have all changed as a result. Our financial futures can no longer go down the paths that almost everyone is counting on, history repeating itself (which is the usual underlying financial planning assumption) is no longer an option.

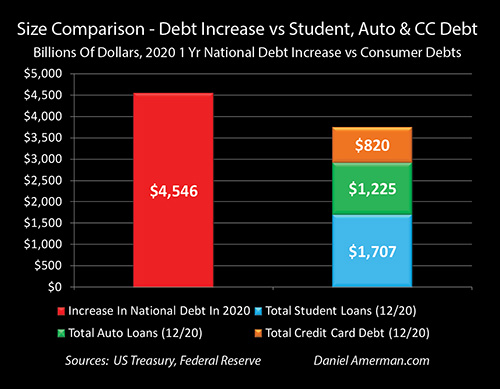

To place what happened in 2020 in perspective, let's compare the one year increase in the national debt to the three largest sources of consumer debt (not including mortgages).

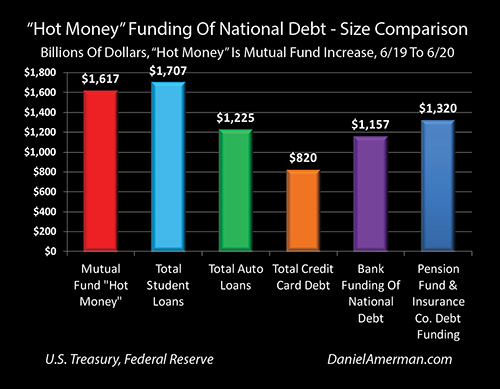

Everyone knows that student loans have becomes an overwhelming problem, with literally tens of millions of people struggling to repay their loans, sometimes unable to buy homes, or even feeling unable to afford to get married and have children. It took decades of borrowing for the national total to reach $1.7 trillion in outstanding student loan debt, and paying for this burden is changing the day to day lives of literally millions of people.

But yet, when we compare total student loan debt to the one year increase in the national debt - the staggering amount of student loans becomes almost minor in comparison, as can be visually seen in the graph above. The total outstanding borrowings to pay for college that built up over a period of decades amount to only 38% of the one year increase in the national debt.

Another major category of consumer debt is auto loans. Cars are a very tangible asset and they are easy to understand, which makes them a tangible way of understanding what is really happening right now, and its unprecedented implications for us all.

Picture yourself on a packed interstate in rush hour traffic in a major metro area, such as Los Angeles, and all the cars on all the streets and all the parking lots - and all the loans used to pay for all those cars. Now expand your vision to thinking about Houston and Atlanta as well, Chicago and Seattle, the rest of the nation and all the tens of millions of vehicles being financed by large loans for all those millions of households.

Add them all up, and we have $1.2 trillion in outstanding auto loans for the nation, with tens of millions of monthly payments being made on all those loans. But yet, when we compare this total outstanding auto debt to the borrowing by the U.S. government in just a single year - the total auto loans are equal to only 27%, or about one quarter of the one year increase in the national debt. Debt that will require its own payments by us all into the indefinite future, as debt is piled on debt.

Credit card debt is an alluring source of spending money that has ended up financially consuming millions of lives, as people struggle to make the interest payments in particular on the money which they may have spent long before. Again, it is no exaggeration to say that millions of people are carrying what is for them crushing credit card debt loads, and that their entire lives are being changed as a result.

What is the national debt? It could be described as something like a credit card debt - the government spending what it can't pay for today, and then making payments on it year after year thereafter, with the interest payments over the years gradually coming to exceed the original amount of the borrowing. But, if we take the sum total of the debt owed by all the credit card borrowers in the nation, which was $820 billion as of December of 2020, and compare it to the tab that the nation's largest spender ran up in a single year - it comes to only 18% of the $4.5 trillion total.

Add up every over-extended consumer credit card borrower in the nation, and they turn out to be a bunch of underachieving cheapskates when compared to the true master of spending more than can be paid for by one's income.

Indeed, when we add the total of the $1.7 trillion in outstanding student loans, the $1.2 trillion in auto loans, and the $0.8 trillion in credit card debt - which accounts for the great majority of non-mortgage consumer debt in the U.S. - then the total comes to what would seem to be the staggering sum of $3.75 trillion. However, when we take this fantastic sum of what pretty much everyone in the entire nation owes altogether (outside of their homes), it is still only 83% of the one year increase in the national debt in 2020.

Crucially, that is before we take into account what the increase in the national debt in 2021 will turn out to be, between the initial $1.9 trillion “stimulus” and the additional $3 trillion in proposed “infrastructure” spending. Not to mention 2022, and 2023.

All of which raises the central question that it seems like very few average people are asking - where is that money coming from? Who lent the United States substantially more money in twelve months than every consumer in the country had previously borrowed in total (outside of mortgages)?

The Funding For The National Debt

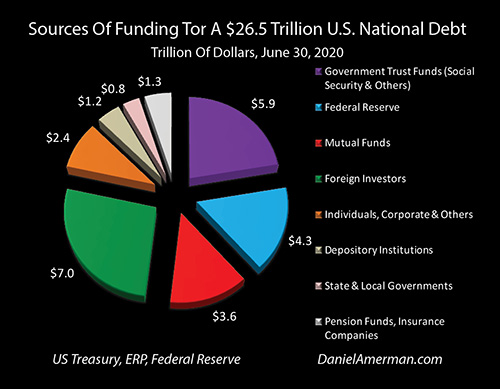

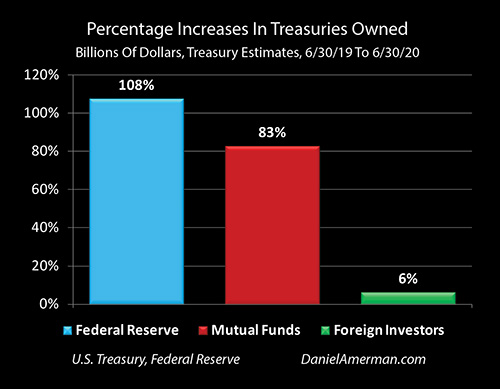

The above represents the U.S. Treasury's best estimate of who it owes money to - who owns the national debt and funds the U.S. government - as captured in the Economic Report of the President, that was provided to Congress in January of 2021. The amounts themselves are from June 30th of 2020, as this sort of information is only irregularly available and not in real time, but it does capture the huge and unprecedented surge in deficit borrowing that occurred in the first half of 2020.

As can be seen, the largest lender to the U.S. government was foreign investors with $7.0 trillion. This was followed by the almost $6 trillion in funding from government trust funds, primarily from the Social Security Trust Funds. The third and fourth largest lenders were the Federal Reserve and mutual funds.

However, when a government has when an enormous, multitrillion dollar appetite for new borrowing, an almost insatiable appetite for new cash, then who funded the previous debt is not as important as who is coming up with the new trillions for the new debt.

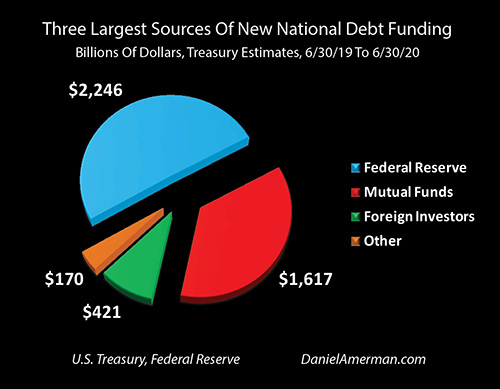

When we just focus on who came up with the $4.5 trillion in new cash to fund $4.5 trillion in new debt in a year, then the picture completely changes - with only three large sources of new money. The largest source of new funds was the Federal Reserve, which funded almost exactly half of the growth in the national debt, funding about $2.25 trillion in new borrowing.

The second largest source was mutual funds, which included money market funds, bond funds and bond ETFs. They came up with a total of $1.6 trillion in new funding for the national debt.

The third source was much less and that was foreign investors funding an additional $0.4 trillion of the new U.S. government borrowing. All other sources of funding in combination came up with a net total of less than $0.2 trillion in new funding, with some sources increasing their funding even while others were decreasing their funding.

Now, for the average person in the street, the size of the national debt is likely an abstraction, the spinning zero's involved in the current rise in the national debt is almost incomprehensible, and it might not even occur to them to try to track who was actually paying for the trillions in new federal spending, who was footing the bill for the stimulus checks and the extraordinary increase in pork barrel spending (never let a good crisis go to waste). In normal times - they would be right. An average person, or average investor really shouldn't have to think about these sorts of things.

However, we're not even in remotely in normal times, and anyone who thinks we are may be due for the reality check of their lives before this is all done. The stability of the entire system - including the economy, the markets, the value of the dollar itself - is based upon a feeding an addict with an insatiable appetite, which is the United States government and its need to suck trillions of dollars out of the system on the one side, in order to throw out trillions of dollars on the other side. If the funding fails, if it isn't there or if the terms become too onerous (much higher interest rates), then the whole system may fail as well.

What it really comes down to then, when it comes to the current and future stability of the system (and all of our savings), is the two big two sources of funding, the Federal Reserve and the mutual funds, and their radical change in behavior.

Funding The Debt & "Hot Money"

To fund half of the fantastic one year growth in the national debt - the Federal Reserve had to come up with the cash to more than double its ownership of U.S. Treasury obligations in a single year. For most of U.S. history, this would have been impossible as the Fed would not have had the money, but in 2008 the Fed gained a new form of monetary creation powers, central banking reserves-based monetary creation, that did indeed enable it come up with the more than $2 trillion to cover half of the growth of the national debt, and more than double its funding of the debt.

Importantly, this was not money printing. And it also wasn't based on the traditional fractional reserve banking that used to drive monetary creation at the level of the commercial banks. As we will be reviewing, this relatively new form of monetary creation which the Fed now refers to as "ample reserves" is done at a level and in a way that used to be illegal (at the level of the central banks), and it is basically what the stability of the financial systems are now based upon for the U.S., Europe, Japan, and much of the rest the world.

Unlike money printing - it doesn't directly create inflation. Also unlike money printing, it is limited, and the closer to the limits that we get, with each additional trillion dollars, then the higher the risks become. As we will cover, there are really good reasons why this used to be illegal, as central banks abusing this power can pervert every aspect of the markets, consuming the economy while effectively confiscating the savings of the nation in order to fund the national debt, with all of this being done in a way that is just complicated enough that the average voter or investor has no idea that it is happening.

The other major source of new funding was mutual funds - and the funding of the national debt by money market funds, bond funds, and Treasury ETFs almost doubled in a single year, increasing by 83%. Generally speaking, there is not nearly that much demand by private investors to fund the national debt, but there were two special circumstances that drew in an extra $1.6 trillion, that would not ordinarily be invested in Treasuries.

The first factor is that as part of a classic "flight to safety" during crisis, massive amounts of money went into what many consider to be safest of all cash-equivalent assets, which is money market funds entirely invested in U.S. Treasury obligations.

The second factor is that for reasons I have been describing for readers over the last several years, and as particularly explored in Chapters 9 & 13, the more sophisticated portion of the market knew that in the event of crisis, long bond prices were likely to rise sharply - as they did. The attempt to profit from this became one of the hottest trades in the markets, as many hundreds of billions of investment dollars that would not usually be invested in Treasuries were used to purchase ten year and longer obligations via mutual funds & ETFs.

When large sums of money quickly pour into a particular market for temporary reasons, it is known as "hot money". Then, when the temporary reason for moving the money ends - the money leaves and goes elsewhere, as there is no natural reason or demand for that money to be in that particular market on a long term basis. While the "hot money" term is most commonly used for money movements in international markets, it can also apply to movements in a domestic market as well, and it is a very good description for where the extra $1.6 trillion in funding for the national debt came from.

Now, if the buyers who fled into money market funds for safety during crisis begin to regain confidence - there is no need for them to keep their money there anymore. The money wasn't there to begin with, there is no natural need, it is financially painful to keep too much money in instruments that don't pay enough interest to keep with the rate of inflation, and outside of crisis, the money is likely to return to its preferred place.

The money is even "hotter" and more subject to flight from the market when it comes to investors making long bond market timing plays, and this is what is really hitting 10 year yields at this time. Generally speaking, people weren't buying 10 year Treasuries to hold them to maturity, but were seeking quick capital gains. These investors don't want the paltry interest rates over time, and they really don't want the pain of ongoing losses, as bond prices fall with rising interest rates. So they take their money and leave, they don't want to fund the national debt anymore (they never did), but the money can only come in to buy them out at higher interest rates, which sends bond prices that much lower, which drives that much more hot money out of the business of funding the national debt.

A Return To A Funding Crisis

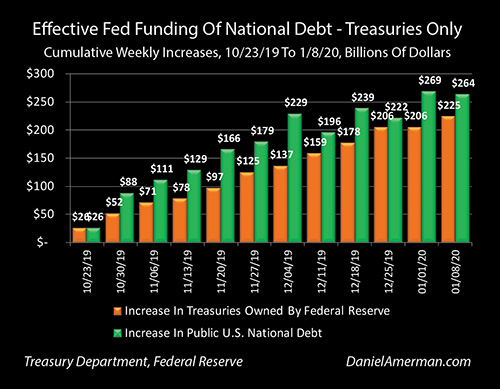

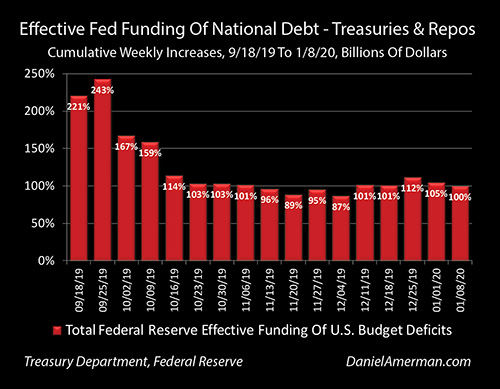

What makes the situation worse is that this is not a new problem, but the resumption of a prior problem that existed before the pandemic, and is now coming back far stronger than it ever was before.

As explored in Chapter 18 (link here and well worth rereading before the workshop), the Federal Reserve made a major, unforced error in the summer of 2019 when it overestimated the market demand for Treasuries, and continued to slowly reduce its holdings of Treasuries. Then the week of September 16th, the Treasury tried to pull over $100 billion in new cash out of the markets, the number of investors wanting to give an additional $100 billion to the government simply wasn't there, and as explained in Chapter 18, the repo market nearly blew up. This threatened not only the stability of the banking system, but to send interest rates soaring upwards, which could have sent the markets crashing downwards.

What the Fed hadn't realized was that the market for the national debt was sated - even in 2019, before the pandemic. The pension funds, the insurance companies, the depository institutions, the mutual funds and the foreign investors - they had just become stuffed full in the process of buying their share of the rapidly growing debt that had reached $23 trillion by that time. There was no natural market to absorb any more trillions in debt, no lenders lining up to give still more, but yet the U.S. Treasury still had an insatiable need for new cash to fund deficit spending.

So, the Federal Reserve did an emergency 180 degree turn, and began effectively funding the growth of the national debt.

Indeed as explored in the analysis linked here that was published very shortly before the pandemic shutdowns, when we include the direct funding of the debt and the indirect funding via the repo market, the Federal Reserve funded exactly 100% of the growth in the national debt between the beginning of the repo crisis and the first week of January, 2020. The Fed did this primarily by using its powers of reserves-based monetary creation, which again, is NOT the same thing as "brrrrrrrrrr" or straight up money printing.

The Impossible, The Irrational & The Fatal Flaw

As explored in the previously linked (and crucial) Chapter 18, there is a fatal flaw when it comes to the free markets funding the impossible - it has to be done in an irrational manner. The biggest borrowings in history would usually require higher and higher interest rates - because that's how it works with free markets, the more investors that are needed, then the more that one needs to pay to get them, particularly if there are rising fears of inflation. Indeed, decades ago in a time of freer markets when the power of the Fed was much less, the "bond vigilantes" could limit the sizes of the increase in the national debt, the deficit spending, by increasing interest rates to the point where the government wasn't will to pay them.

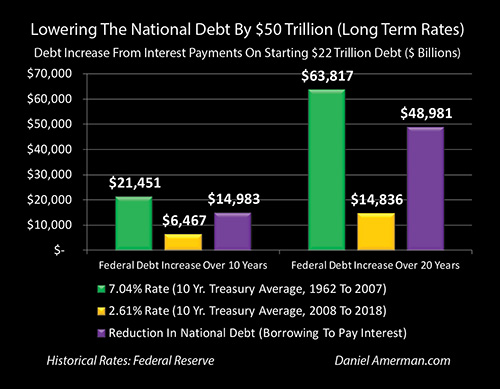

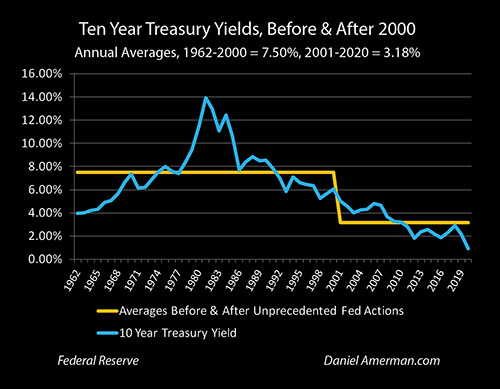

However, as covered in Chapter 17 (link here) of my free book, if we did pay free market interest rates, such as the average 7.04% 10 year Treasury rate between 1962 to 2007, that by itself would create a near $50 trillion increase in the national debt over the next 20 years, because the government borrows the money to make the interest payments, and borrowing more money to pay higher rates sets off a compound interest loop that consumes everything.

Now, that's based on a $22 trillion national debt, at the current $28 trillion debt (for this month anyway), that would become more than a $63 trillion increase in the national debt just from borrowing to make interest payments alone, with no other deficit spending in 2021 or beyond.

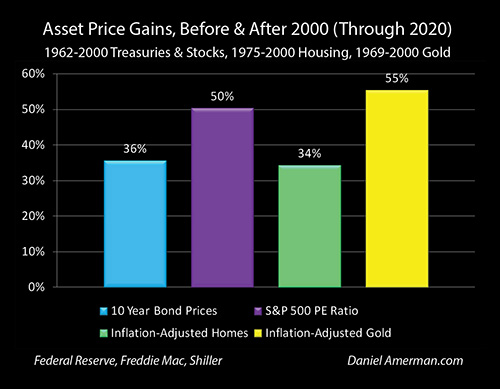

There is also the critical issue as particularly explored in Chapters 18, 1 (link here) and 10-11 that the current highly elevated levels for bond prices, stock prices and housing prices are all dependent on the continuation of some of the lowest interest rates in financial history. If pulling in the money via the markets to fund the highest deficit spending in history were to materially increase interest rates, then bond prices, stock prices and housing prices could all be at risk.

This then leaves us with the need for irrational rates to fund the impossible debts. Ten year Treasury yields reached record lows in 2020, even as the increase in the debt reached record highs. This is the direct opposite of free markets, and it is the "fatal flaw" when it comes to markets funding the national debt.

We already had a completely sated market for the U.S. national debt by the time it had reached $23 trillion in 2019. Every normal source of funding for the debt was just stuffed as full of Treasuries as they could be, there was no appetite for any more at the interest rates that then prevailed - and the Treasury has since rapidly piled on another $5 trillion in debt, even while the Fed forced interest rates down to much lower levels.

The new money that needs to come in to fund the national debt, just to replace the hot money that wants to leave, is a staggering sum by itself, as can be seen above. It is almost equal to the total for all student loans outstanding. The current mutual fund "hot money" that has no long term interest or reason to be funding the national debt towers over total auto loans for the nation, or total credit card debt. It is much greater than the total banking and other depository institution funding of the debt. It is also larger than the sum of all pension fund and insurance company funding of the national debt.

And that's before any new borrowing in 2021 or 2022.

The impossibly high new levels of borrowing in 2020, 2021 and beyond can't possibly pay market rates to bring in the new cash, or two "doom loops" of a sort get set off, with a rapid compounding of the national debt as the cash is borrowed to make higher interest payments, even as the financial markets potentially crash because of much higher interest rates.

What we are seeing with 10 year Treasury yields going back above 1.70% as of Friday (which is still very low from a historic perspective), is the mutual fund "hot money" starting to demand at least a little rationality when it comes to parking their money in the national debt. This then creates a major dilemma for the Fed and the U.S. Treasury, because there are limits to how much money they can access through reserves-based monetary creation, they don't want to use that up on the front end and would rather have private investors providing at least part of the money to fund the national debt. However, at the same time, paying rational rates to private investors could explode the size of the debt upwards even while bringing down the markets.

There is nothing stable about this, it is a huge dilemma on a scale that we have never seen before. The Fed's ability to handle not just the current $1.6 trillion in hot money, but also the new $1.9 trillion in deficit spending, and whatever the tab comes in for the rest of 2021 - is all based on unproven theory. This is totally new ground for the national debt, the markets, and the nature of money itself.

Out of the three broad paths for the future that we will be exploring today (link here), this is the first path, where if the new theory for the nature of money works out and the bureaucrats at the Federal Reserve are up to the required high wire balancing act, then it is indeed possible for the Fed to continue to pull this off - to fund the fantastical growth in the national debt in a stable fashion, at near zero percent short term interest rates, and to do so without crashing the markets.

To be clear, however, while it could be quite stable, it won't be "normal". The path back to normal closed with the $4.5 trillion increase in the national debt in 2020, and we will be moving much farther away from the old normal in 2021. This is emphatically not “free money” but a fundamental change in the nature of money, the markets and the economy, to an extent that is ironically being missed by those who believe it is “money printing”.

The full implications over time could even be called an effective silent takeover of sorts, with the actual financial mechanics of the funding of the trillions in new debt just happening to have the side effect of delivering a much greater control over the nation’s money and how it is distributed to the insider triumvirate of the Federal government, the Federal Reserve and Wall Street. The greater the funding of the national debt over time – the greater the resulting centralized control over the economy and the distribution of wealth. This shift would be on a more or less permanent basis – as permanent as the new national debt - and all with no press conferences to announce what is in process, no public discussion or voting on it, and no understanding by the average person.

The other two paths will also be very much in play in 2021 (and 2022) as well. There is the second path, the possibility that the political appointees and career bureaucrats at the Federal Reserve are not up to the task of pulling off perhaps the greatest monetary experiment in history (their track record isn't great even with far less pressure and risks), and they crash the system instead, leading to a new and greater Financial Crisis.

There is also the third path, where faced with pressures it can't handle, and perhaps even in the midst of a developing crisis, the Federal Reserve does the make the move to using straight up "money printing", i.e. unlimited monetary creation that is no longer based on limited reserves, in order to fund the insatiable appetite of the Federal government for more money. This hasn't happened yet, but it could, and if it does then all our financial futures are likely to be traveling a quite different path over the coming years.

Three paths forward, and what they all have in common is that none of them lead back to the past. The financial world has fundamentally changed and it is continuing to change in a dynamic fashion, month by month in real time, as formerly impossible amounts of debt "must" be financed at irrationally low rates, in markets that are already sated with no appetite for new government debt, with no certainties and no safety net beneath us.

Learn more about the free book.

**********************************************