Chapter Five

Three Beautiful Arbitrages (Why Yield Curve Inversions Happen)

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetSimply put, yield curve inversions are what happens when too many investors try to crowd into the same arbitrage opportunity at the same time.

The predominately institutional investors who attempt this trade are not acting out of fear - instead, they see an unusually good opportunity to make money. And what history shows is that with this particular opportunity - they are right to crowd in, because the track record is outstanding.

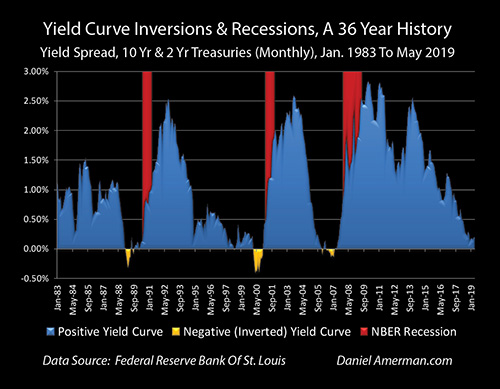

As will be explored herein, this particular arbitrage opportunity has only come about 3 times since 1983 - and all three times, it has worked spectacularly well. So much money has flooded into this trade in three different time periods that it has turned bond market pricing and yields upside down, and all three times - the market has been right. The end result for the markets (on average) has been three beautiful arbitrages, each successfully executed (and a very high degree of reliability, if we go farther back in time).

Now as it happens, this particular arbitrage requires anticipating a recession. The trade does not involve directly investing for recession, which can be messy and imprecise, but rather investing in a much cleaner and more reliable alternative, which has a perfect correlation with recessions in the modern era.

What is unfortunate is how this extraordinary track record of profit-seeking fixed income professional investors successfully executing arbitrages, is being presented to many equities oriented individual investors. A potential yield curve inversion has captured the markets' attention, and to read some accounts, it is almost as if some fearsome apparition has appeared out of nowhere, with a near perfect track record of prophesying doom, and therefore investors are supposed to scurry around in fear. The emphasis has been on the almost uncanny degree of correlation, and not causation.

Yield curve inversions are much more interesting - and more powerful - than what can be seen from that perspective. When inversions and how the causation actually works are better understood, then the relationship with potential recessions can also be much better understood.

Even more importantly, there are aspects of how the institutional market creates the arbitrage that are little understood by many individual investors - but could be very useful to understand if we do get another inversion, and if there is indeed another recession that follows.

In general terms - because of "sequence of returns risk", a recession in 1-2 years could be financially catastrophic for many millions of retirees and retirement investors This would be particularly true if, like the last two recessions, it is accompanied by the popping of asset bubbles in the investment markets.

How institutional investment professionals can look at the same situation and see not disaster but unusually good profit opportunities, is something that is worthwhile to examine and think through. Now, the specifics are quite different for what individuals can do, but the perspective can carry over, and be potentially be quite valuable, particularly if there is another recession in the near term.

Even more important is how the institutional arbitrage that creates inversions is not based on "playing" the anticipated recession directly, but rather the more reliable path of playing the Fed's expected response to the anticipated recession. Seeing the world in this way can require a different mindset for individuals, but there are really good reasons why many professionals approach the markets in that way, and these reasons can also be of critical importance for individuals when investing for a world that is increasingly dominated by Federal Reserve interventions and the associated cycles of crisis and the containment of crisis.

This analysis is the fifth chapter in a free book, an overview of the rest of the book is linked here.

Causative Factor 1: The Fed Increasing Interest Rates

This analysis builds upon a primer on yield curve inversions, which I wrote this past summer and is linked here. The primer is a nine step analysis which begins by explaining in layman's terms what yield curves and yield curve inversions are, what the history is, the critically important relationship between Fed rate increases and inversions, and the causative reasons why inversions can be such an accurate early indicator of coming recessions.

As explored in the July analysis:

"... yield curve inversions generally occur when the Federal Reserve has been boosting interest rates. Because the interest rates that the Federal Reserve raises are short term, this tends to push the short term up relative to the long term, which is exactly what has been happening."

"...all it potentially takes is the Fed following its publicly stated game plan of increasing rates by another 0.50% before the end of 2018, with that continuing to have a larger impact on short term than long term rates, and that could be enough to produce an inverted yield curve by the end of 2018."

As of early December of 2018 - that is exactly where we are.

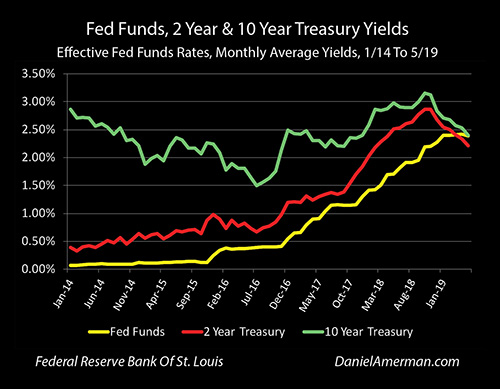

The yellow line shows the stair step pattern of 0.25% increases in the effective Fed Funds rate, which has been following the quarterly targeted increases set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The next stair step is widely expected to occur at the December 2018 meeting of the FOMC.

As covered in the primer, the red line of 2 year Treasury yields is not the same thing as the yellow line of Federal Reserve rates, but short term Treasury yields have been rising with Fed Funds over time.

As of the close of the markets on December 7th, 2018, the 2 year Treasury yield was 2.72%, the 10 year Treasury yield was 2.85%, and the yield curve spread was down to a mere 0.13%.

Causative Factor 2: Investors Attempting To Profit From Recessions

Cycles of rising short term interest rates are more common than yield curve inversions, and they do not necessarily lead to either inversions or recessions. The Fed has raised interest rates many times, and many of these cycles over the decades have been much larger than the 2.0% increase in Fed Funds rates seen to date.

Why inversions are so much rarer is that generally speaking - investors almost always require higher yields for risking their money for a longer period of time. If short term interest rates rise - then so, generally, do long term interest rates.

Even if the repayment of principal and interest is considered to be riskless, there is nonetheless the issue that the longer term of the bond, then the greater the risk of an episode of higher inflation that could sharply reduce the value of later bond interest and principal payments before their receipt. There is the also the issue that the longer the term of the bond (all else being equal), the greater the change in price for any given change in yield, and therefore the greater the risk that the investor will take a substantial loss if they sell their bonds before maturity.

Rational investors do not take on double increases in risk without really good reasons - so, with somewhat rare exceptions, yield curves are almost always positive, and usually substantially positive. When yield curves do go flat and then invert, it is not some minor technical indicator for finance wonks, but rather the entire term structure of interest rates is rearranging and going to an unnatural place - and there have to be very strong fundamental reasons for this uncommon event to occur.

A good explanation - which has also been very much in the news lately - is that long term bond yields go beneath short term yields because the institutional investors who dominate bond markets believe there is a very good chance of an economic slowdown or recession in the near term, somewhere most likely in the next 1-2 years.

Again, from the primer:

"...if lower economic growth is expected, then less of a premium is required to compensate for inflationary expectations, and long term yields should be falling relative to short term yields."

"Another key factor is the role that profit-seeking institutional investors play in changing the yield curve when their expectations for future economic growth change. If a slowdown in economic growth or a recession is expected, then professional investors know this will almost certainly be accompanied by the Federal Reserve decreasing interest rates.

Because bond prices move the opposite direction from bond yields, this will increase bond prices, and of particular importance is that this will then disproportionately increase long term bond prices relative to short term government obligation prices. It now becomes rational to demand higher yields for short term notes than long term bonds, as a reward for missing out on the expected capital gains in long term bonds."

When the yield curve nearly converged in November and the early days of December - it wasn't a Fed interest rate increase that did it, because there wasn't one during that period. Instead, all the compression was driven by 10 year yields falling from a peak of 3.24% on November 8th to 2.85% on December 7th.

Long term rates fell by 0.39% in less than a month - which was greater than the Fed's recent pace of 0.25% increases every three months. However, once we understand the fundamentals for why yield curve inversions matter - and why they have a perfect record for calling the last three recessions over 35 years, and an excellent record over the longer term - then we can see that not all convergences are created equal.

Convergences driven by the "floor coming up", by the Fed increasing interest rates, are the result of a committee meeting and voting every now and then. Now, the FOMC is an extraordinarily powerful committee, their decisions can send the markets soaring or crashing - and they make mistakes. However, that said, we have a very long history of Fed interest rate increases, and few individual increases are by themselves any sort of game changer for the markets or long term investment strategies.

Convergences driven by the "ceiling coming down", and long term rates rapidly falling relative to short term rates, are a much more serious matter. When the entire term structure of interest rates rapidly distorts because of concerns about the economy - that is a far rarer occurrence than the occasional plunges in the Wall Street indexes. For all the screaming headlines they draw in the moment, most of the highly dramatic one day or one week stock index plunges turn out to be much ado about nothing when viewed from the perspective of 5 or 10 years later.

In contrast, yield term inversions are somewhat rare. We've only had three of them in the last 35 years. Each one of them is highly individually memorable - because each one them was a perfectly accurate warning indicator of fundamental coming changes in the economic and interest rate cycles.

What drives these somewhat rare but highly accurate events is the fixed income markets collectively making an unusual but highly profitable bet: they think economic growth is in big trouble in the near future, there is a fast rising chance of recession - and because Fed cycles are burned into the consciousness of professional investors to a far greater degree than with most individual investors, these investors move right past crisis and into the containment of crisis - the Fed will slash interest rates to try to get out of recession.

Buying long term bonds close to the end of a cycle of rising interest rates, holding them, and selling them when the Fed has smashed interest rates to the floor, is one of the most lucrative things a fixed income professional can do, in terms of long-only strategies. From that perspective - seeing a looming change in the economic cycle triggering a change in the interest rate cycle is like hearing a dinner bell being rung.

Having spent much of my career on the fixed income institutional side, this is one of the critical aspects of the markets, but yet it can be difficult to communicate to even very well read and educated individual investors whose careers have been spent in other areas.

Conventional long term individual investment strategies are generally based on reliably rising stock market prices, the compounding of significant interest income payments, and perhaps a real estate kicker as well with REITs or at least rising home equity. Because a recession can play havoc with stock prices, real estate prices and interest rates - it might be natural to hear this talk of yield curve inversions and near perfect track records for predicting recessions as being some very dark and pessimistic talk.

Many typical investors might therefore accept or reject this yield curve information based on their emotions, the way they want things to be, and the confirmation bias filter they use with regard to their chosen retirement investment strategies.

What is fascinating is to contrast that perspective with the perspective of where yield curve inversions fundamentally come from, what the motivation is for market participants when they create an inversion, and the investment results in practice.

Viewed from a bond buyer's perspective, the 35 year perfect history of inversions preceding recessions is the history of three beautiful, golden, glittering arbitrages executed to perfection.

On only three occasions over those decades, the institutionally dominated fixed income markets as a whole voted that a change in state would be coming in the next 1-2 years, and they felt so strongly about it that they completely distorted the natural shape of the yield curve, buying long term bonds with both hands in anticipation of the coming change in the interest rate cycle.

On all three occasions the markets were correct that an official recession would arrive in 1-2 years. Think about that. The markets aren't supposed to be that good, not that far in advance. But with this one type of situation, in practice they have been.

Getting The Causality Correct

It is only when we understand the sources of inverted yield curves, that the critical element of causation can be understood. Inverted yield curves do not in any way, shape or form "cause" recessions.

But - the uncommon event of a preponderance of institutional investors strongly anticipating a change in the economic cycle and acting in their own financial interests, will through their actions quite directly cause the creation of a relatively rare event - an inverted yield curve.

The pursuit of arbitrage opportunities by a horde of sophisticated investors is what causes inversions. The movement of money that is involved in causing these somewhat rare events is enormous. The track record for the successful execution of the arbitrages is remarkable. So while there is no actual guarantee of a fourth recession, yield curve inversions are something that emerge from the very heart of the financial markets and knowledgeable investors acting in their own self interests, and as such, should be taken very seriously indeed.

Picking The Best Cycle To Arbitrage

There is particular information value in one aspect of the three successfully executed arbitrages - and that is what the arbitrage target was.

The reason for entering into the arbitrage strategy - with so many investors crowding together to try to do it at once that they fundamentally distort the term structure of interest rates - is to try to make money off a particular economic cycle, with that being one of the recessions that periodically alternate with expansions as part of the overall business cycle.

But the problem with attempting to directly arbitrage a future recession by itself is that they can be.. well.. messy and unpredictable. To do it well could require correctly calling things like when it hits, how long it lasts, how deep it is, what sectors and regions are hit and when, as well as the particular path that might be traveled by investor psychology in a market.

So, even if the big picture of a recession starting in 1-2 years is called with great accuracy, there are still a whole lot of other details to work out. And if the complexity of the details turn out differently than anticipated, then quite a bit of the potential profits might not be realized as well.

On the other hand, if someone invests for an on-off switch, and they know with perfect certainty that the switch will be flipped to "on" in the event of a recession - then they have a much better chance of succeeding with their attempted arbitrage. Just get the future occurrence of a recession correct (which is difficult enough), invest for the "on" switch being turned on, and so long as the recession occurs - so will the profits associated with the "on" switch.

Enter the Federal Reserve.

What the Federal Reserve does in the event of a recession is not a mystery or any form of "random walk." As soon as the Fed thinks a recession is imminent, or finds that they are already in a recession - they will flip the "on" switch.

The Fed has a mandate to maximize stable employment, which is done by growing the economy. If there is a recession, then the Fed treats exiting that recession as soon as possible as an existential event. The primary tool in the Fed playbook to do this, something they do every single time, is to rapidly lower interest rates.

This lowering of interest rates is not a subtle process - it is smashing a hammer down, fast and hard. The last two recessions the Fed has rapidly lowered Fed Funds rate by in excess of 5%.

Now, the longer the term of the bond, then the greater the profits (all else being equal). Yes, because yield curve spread compressions and expansions are generally contracyclical with regard to Fed interest rate cycles, the Fed smashing short term interest rates downwards generally leads to yield curve spread expansion, and the changes in long term yields are not as great as the changes in short term yields.

But even with longer term bond yields not moving as much as short term yields - they are still where the great majority of price increases (i.e. capital gains) will occur.

So when arbitrage seeking institutional investors believe the cycle is turning and recession is likely back on the way, then they have powerful incentives to invest not necessarily directly for the vagueness of some kind of recession, but for the highly reliable on/off switch of what the Fed will do to interest rates in the event of recession. The maximum profits if the switch flips to "on" are on the long end, they all know it, and a crowd of investors piling into long term bonds in the search for capital gains can drive prices so high - and long term yields so low - that it can create the oddity of a yield curve inversion.

It is also worth noting that not all the profits are on the back end, not by any means.

Recently, both the stock markets and the bond markets strongly reacted to growing fears about global growth - and the US economy. At one point on Thursday, December 6th, the Dow was down over 1,500 points in 2 trading days. At about the same time, the 10 year Treasury yield was briefly touching 2.83%, which was a reduction of 0.41% from the 3.24% peak on November 8th.

While both radical market changes were in reaction to the same thing - the stock markets were experiencing a blood bath. On the other hand, the intense demand for long bonds meant that those who owned such bonds were making money hand over fist. Particularly when it is the "ceiling coming down", when long term yields are falling down to converge with short term rates, then inversions and near inversions can be highly profitable for investors, even over the short term.

So, investing for recession by buying long term bonds is not necessarily a buy and hold strategy. But rather, there is an expected trend line, and whatever the frequency of trading (and as with any other type of investing), being aligned with the underlying trend line increases the chances that the cumulative series of trades will be profitable over time.

A Framework For Opportunity Identification

The contrast between where yield curve inversions come from, and how they are often being presented, is both fascinating and unfortunate.

1) Yield curve inversions are presented as being fundamentally negative - but they are created by large numbers of institutional investors distorting prices in the (quite successful) pursuit of large profits. Extraordinary sums of money have been made in the process, with what has historically been a very high degree of reliability.

2) Yield curve inversions are based on arbitraging cycles.

3) Yield curve inversions are also based on understanding the heavy-handed interventions by the Federal Reserve that have been particularly dominating markets over the last almost 20 years - and arbitraging the market changes caused by those often quite predictable massive interventions.

However, the arbitrage components above can be difficult for many investors to understand and identify - because they are not part of traditional individual investment strategies, or retirement financial planning.

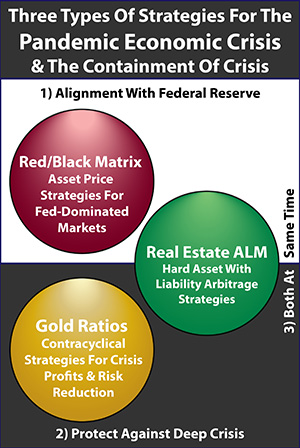

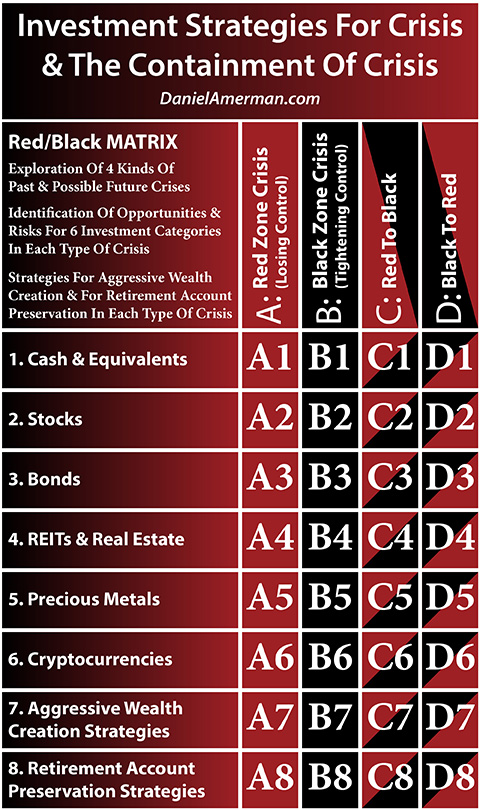

I created the Red/Black matrix below as an organizational analysis framework for the identification of both the risks - and the opportunities - that arise with different cycles, different investment categories, and the different Federal Reserve interventions that have been occurring at different phases in the cycles.

(2019 Cycles Overview pdf link here.)

The A-D columns are the cycles, and rows 1-8 are the investment categories and strategies for each of the cycles.

For positioning relative to other analyses, this analysis has been entirely about matrix cell D3, which is the intersection of the #3 row of Bonds, with the "D" column of a cycle of the containment of crisis transitioning to a cycle of recession and crisis. This extends the recent previous analyses which have explored the B4 and D4 cells for real estate and REITs, as well as more of the C and D columns with regard to options being considered by the Federal Reserve and the OECD.

Theory, Practice & Market Track Records

In theory, investment prices are supposed to be determined by knowledgeable investors acting purely in their own self-interests. Within a market as a whole, the sum of all these investors seeking profits from pricing discrepancies then becomes a discovery process that finds the correct prices for each investment at any given point in time, based upon the best information available at that time.

At the very heart of yield curve inversions - is that exact process.

Large numbers of professional investors who watch economic and market data on a daily basis, think they see an opportunity to make money. Every now and then - less than once every ten years in recent decades - so many of them pile into that perceived profit opportunity at the same time that they bid prices for long term bonds up to a very unusual place - and the oddity of an inverted yield curve is created.

Profit-seeking investors have done this three times since 1983, creating three yield curve inversions - and a recession has followed all three times. There have been three official recessions since 1983 - and each recession was preceded by so many investors seeing it 1-2 years in advance, that a yield curve inversion always occurred.

We can go from inversions to recessions, or recessions back to inversions, but either way, it was three for three, with no false positives and no missed recessions. That means in practice that there were three beautiful arbitrages for an entire market, and (on average) the profit-seeking investors were rewarded each time with major profits.

Now, that does not mean that if a fourth inversion occurs that there will necessarily be a fourth recession within about 1-2 years thereafter. Perfection is hard to maintain, and the future is never certain.

However, while the future is never certain, it could be a big mistake to too easily dismiss yield curve inversions as being some random coincidence, perhaps while blithely saying "correlation is not causation".

Yield curve inversions are not random, they are not coincidences, and they are not about rolling around the ground while shouting "the sky is falling". They are not about pessimism but are about making money - serious money. And what they represent is not a fluke - but an entire market making a call.

Now, an investor might say that the stock market isn't pricing in a recession, so it is unlikely. And that could be considered mostly true, although the stock markets have seemed to be moving in that direction lately.

But if an inversion does occur and it does persist over time - then it could be said that the bond market is indeed calling a recession. And let's face it, as partially reviewed in this analysis, the simple facts are that the bond market has a MUCH better track record for unambiguously calling recessions well in advance than the stock market does.

Yield curve inversions are quite uncommon, they sound a bit technical, and as such, are they often little understood by most investors. Such inversions can, however, have extraordinary practical implications for all investors, and I hope that you have found new information and new perspectives about this important potential market development in this analysis.

*******************************