The Interest Rates Needed To Fund A Government With A Voracious Need For Cash - Early Problems Appear

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

TweetThe United States government has a voracious need for new money - but with an over $20 trillion debt, it can't afford to pay higher interest rates over the long term. The Federal Reserve is currently going through what could be called a market liberalization cycle, or a quantitative tightening cycle, where it reduces the supply of artificial money, and lets the market fund more of the federal debt with real money at higher interest rates.

That is a daunting task - how to get huge sums of money without paying whopping interest payments that would send the national debt upwards and out of control. How are the U.S. government and Fed going to do that? Is there a well thought out and brilliant plan for doing so?

Early indications as seen in the market this week, is that there is no plan, they have no idea how to do this, and they are just going ahead anyway. The government needs the money to feed a politically created major increase in deficits, so it is borrowing, the Fed's textbook says this is the time in the business cycle to raise rates, so it is raising, and the two trains are speeding down the track straight at each other.

The government just sold $126 billion of Treasuries on Monday - and it had difficulties, which meant it had to pay higher interest rates. That was before auctioning the $169 billion planned for later in the week, to fund the government's deficit driven need for about $300 billion in cash in a single week.

Two applicable quotes can be found in the March 27th Wall Street Journal article "U.S. Government Bonds Fall on Wave of Supply", by Daniel Kruger (link here).

"The notes attracted below-average demand, underscoring the difficulty of selling an increasing amount of bonds into a market in which yields are rising."

'"The Treasury's financings are going to become a bigger issue for the market to absorb," said Kevin Giddis, head of fixed income at Raymond James. "The likelihood of keeping yields where they are is not good."'

This analysis is part of a series of related analyses, an overview of the rest of the series is linked here.

The Trickle Before The Flood

Having to borrow $300 billion in a single week is not a good sign when it comes to responsible fiscal stewardship by a government. In this case, there is no doubt that both parties decided to ignore long term issues of the government debt in order to meet short term political goals - which is of course, how government debt issues get created in the first place.

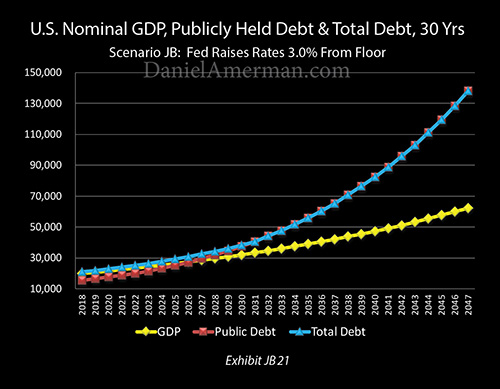

That said - $300 billion is miniscule compared to what is on the way, when it comes to increases in the national debt and the need for the funding of that debt. As covered in the analysis linked here, when we look at government projections for the increases in the national debt need to pay for Social Security and Medicare, future deficits, and future interest payments (with the Fed's planned interest rates increases), then the total national debt in 30 years will be $138 trillion, of which $54 trillion will be the sole result of the Federal Reserve raising interest rates.

Looking at a current national debt of just over $21 trillion (which will likely fall next month with April income tax collections), that is a total increase of $117 trillion in debt that will need to find buyers, with a little less than half of that being the result of higher interest rates, and a little more than half being other long term expected government financial problems. Borrowing $300 billion is only about 0.25% of the longer term total increase, so it is trivial in comparison.

That leads to the bigger question - if higher interest rates have to be paid to come up with another $300 billion, but 400X that $300 billion is needed, then where does the additional money come from and how high of interest rates need to paid?

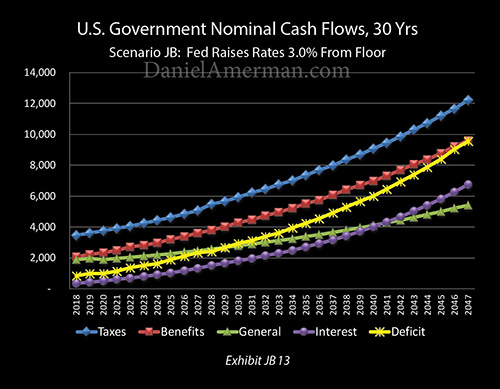

The purple line in the graphic above (also from the linked analysis) shows the extraordinary acceleration of interest payments that occur as a result of compound interest on the Fed's interest rate increases, which feeds into a fantastic increase in speed for the yellow line of annual deficits.

And if still higher interest rates have to paid to get the investors to fork over another over $100 in trillion in cash - what does that do the level of the national debt and the fiscal solvency of the U.S. government? Keeping in mind that the compound interest component means that the increase in debt would be an exponential function?

What is our new purple interest payment line, what is our new yellow deficit line, and how many more tens of trillions then need to be borrowed at what interest rates?

What was seen for real in the markets this week with regard to weak demand and higher interest rates for getting the $300 billion in cash needed by a hungry government, is just a miniscule triviality compared to what could be on the way.

Information Value versus Gloom & Doom

Now, the preceding is some very scary stuff, and if I were an actual Gloom & Doomer, this is where I would really get rolling with the inevitable financial destruction of the government and the dollar that is on the way with 100% certainty, etc., etc.

Don't get me wrong - that could very well happen and sooner than one might think. In fact, it's starting to look a lot more likely than it did. It is the 100% certainty part, the absolute foreknowledge of the future part that I have to take exception with.

As I have written about extensively in the past, there are well understood ways of keeping this doomsday scenario from happening, and of maintaining stability into the indefinite future.

But it is difficult to do that, and such an outcome is highly unlikely to happen by accident. This is particularly the case given the situation of starting with a very high national debt and then meeting the historically unprecedented future financial demands of Social Security and Medicare on top of that. For a nation to get through that situation while maintaining solvency and stability requires a government and central bank working together to implement a disciplined plan over many years.

And the information value of the last few weeks and months is that (at least for now) there is no plan, there is no coordination, and the government and the Fed are now each doing their own thing for what makes sense to them in the moment, without being particularly concerned about what the other is doing or what the impact will be in the future.

The Investment Implications Matrix

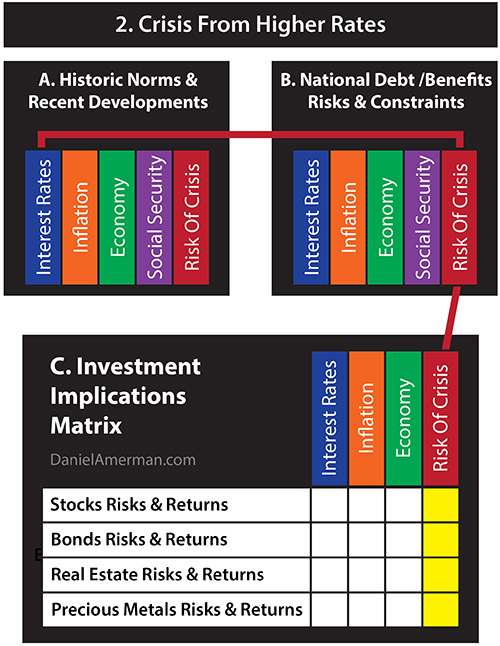

I do find the "Investment Implications Matrix" (overview linked here) to be helpful for understanding the financial and investment implications of these kinds of issues.

What we saw with the market feeling even minor digestions pains for a mere $300 billion in government debt is a bad sign that the Fed increasing interest rates (the "A" box) at the same time that the national debt is huge and growing fast (the "B" box) runs the risk of setting off a crisis of rates rising even faster than the Fed plans, which could have a major impact on all the markets, as shown in the yellow cells (the C" box).

This would then further exacerbate the risks discussed in the preceding "The ABCs Of Popping A Third Asset Bubble" analysis (linked here), which looked the A-B-C-Ds of how two market "movie plot lines" have played out in the modern era, with a similar set of Fed actions eventually being followed by market bubbles popping and powerful recessions.

This then feeds into the top two headlines of the print edition of the Wall Street Journal on March 28th, 2018. The article titled "Climb in Key Rate Pinches Borrowers", looked at a short-term rate that has been climbing faster than Fed Funds, which is Libor, and the more than 2% increase it has seen since the Fed began raising interest rates. A key quote from the article is:

"Libor's recent ascent appears to have been driven by factors such as rising short-term debt sales by the U.S. government..."

So the Fed raises rates simultaneously with the government increasing borrowing, and the results spill over into the approximately $200 trillion in global dollar-based financial contracts which are Libor-based. This means that the 2% increase in Libor rates, of which the Fed rate increases are the main component, are already taking an additional $4 trillion a year away from borrowers. The impact on the financial sector is almost as great as all U.S. government non-interest spending, and it is happening right now.

That then takes us to the top Wall Street Journal headline of "Tech Worries Drag Down Stocks", and an eye-popping graphic of the damage done to leading tech stocks during the March 27th sell-off.

Everything is interlinked, and in ways which could be following historical patterns in some ways, but are unprecedented in other ways.

In the face of a tech stock sell-off which is reminiscent of the tech asset bubble and the recession that followed (A-B-C-D), the Fed is following the same policy of increasing interest rates. The world is in general much more in debt than it was, so the increase in interest rates is sucking cash and profits away from borrowers on a far greater scale than was previously the case.

And even in the earliest stages of the massive increase in governmental spending that is on the way - the market is having issues with coming up with the money without receiving higher interest payments. The other critical, critical concern is the reappearance of several of the fundamental drivers of inflation, which historically can be the largest source of higher interest rates of all.

Doomsday Is Not Guaranteed

The above does seem a bit on the bleak side, and as stated previously - the chances of ending up in a very bad place are real and are continuing to increase.

That said, I remain absolutely convinced that some sort of doomsday crisis is not at all inevitable. We can see concrete evidence of this across the Pacific Ocean today, and the real world proof for how these risks can be contained will be the subject of an analysis that I hope to get out soon.